In its 1911 inaugural issue, the Women’s Eastern Times (Funü shibao) printed a composite photograph of embroiderer Shen Shou (1874–1921) together with her work—an embroidered portrait of the Italian queen Elena of Montenegro (1871–1952). A caption slip pasted onto the embroidery states: “Commendation from the Empress Dowager to bestow [upon her] the character ‘Shou’ [longevity] by imperial decree / [This is an] embroidery work by Yu-Shen Shou, the imperially appointed principal instructor of the Embroidery Program for Women at the Ministry of agriculture, Industry and Commerce”.

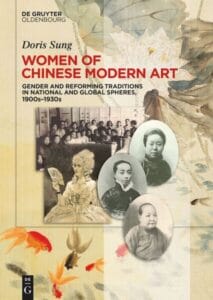

Excerpted from Women of Chinese Modern Art. Reprinted with permission from De Gruyter Brill.

Although the embroidery depicted a foreign queen, the editors of the Women’s Eastern Times reiterated Shen’s accolade of receiving a calligraphy scroll with the character “Shou” (longevity) from the very hand of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908) and her subsequent appointment to the post of principal instructor in 1904. The creative juxtaposition of the caption slip and the embroidery was the editors’ way of ensuring that the imperial endorsement by the Qing empress was not lost on the reader as the inaugural issue was published in June 1911 (a few months before the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the end of imperial rule).

The images and caption on the page of this nascent genre of popular publication must have left Chinese readers puzzled over its incongruity—a portrait of an Italian queen was an unlikely subject to be undertaken by a female embroiderer from Suzhou. And how did Shen, a slight young woman from the lower Yangzi region, get noticed by the de facto ruler of China, eventually being appointed to an official post in her court? And how did she earn the title of “present-day goddess of needle” from the late Qing official and renowned intellectual Yu Yue (Quyuan jüshi, 1821–1907) in the colophon he wrote on Shen’s four-panel embroidered screen of flowers and birds? The stories behind these images roused curiosity while at the same time foreshadowing the promises of the newly sanctioned public education for women in 1907 as part of the “new policies” backed by Cixi. They also reflected the new possibilities of a traditional practice that invoked long-standing gender norms.

Shen Shou – The Goddess of Needle

Shen Shou (1874–1921) was born Shen Yunzhi into a family of antique dealer- connoisseurs in Wu County (Suzhou). Like many girls in the Suzhou area at the time, she started learning embroidery from her mother and sister at a young age. Suzhou-style embroidery (Suxiu) was noted for its fine stitching and vibrancy of colors and had long been a favorite of the Ming and Qing imperial courts. Not only were imperial workshops set up in Suzhou to produce embroidered textiles for the court, but private workshops (xiuzhuang) were also established to fill domestic orders and, eventually, foreign ones. Some of these private workshops would fulfill orders by hiring women embroiderers to produce works in their own home via a putting-out system called baokou. The Shen family women were part of the cohort of embroiderers who produced work on demand in this supply chain.

In 1893, when Shen was 20, a uxorilocal marriage was arranged for her with Yu Jue (1868–1951), a minor government official in Zhejiang who had obtained the juren rank in the provincial civil-servant examination. Yu was an adept painter and calligrapher who drafted many of the underdrawings for Shen’s embroidery. He was also an opportunist who was eager to move up to the echelon of high government officials, and in 1903, having heard from an acquaintance in the court that the Empress Dowager Cixi had a special fondness for fine embroidery, he persuaded Shen to embroider a series of works to be presented to the empress for her seventieth birthday the following year. Among the pieces was a vertical hanging depicting the eight immortals offering birthday wishes to the Queen Mother of the West. The works made it to the court in Beijing in 1904 and were presented to Cixi by the minister of commerce, Prince Zaizhen (1876–1947), who was a close ally of the empress. Cixi was reportedly fascinated with them, and bestowed Shen and Yu with her calligraphy of the characters Shou (longevity) and Fu (good fortune). Thereafter, Shen Yunzhi changed her given name to “Shou” to memorialize the honor. Shen and Yu were also awarded a “Fourth-Ranked Medal of Trade” by the Ministry of Commerce. This medal was the highest award for achievements in the arts and crafts given out by the court at the time. Shortly after, Cixi issued an edict to appoint Shen to be the principal instructor of the Embroidery Program for Women at the newly amalgamated Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce; Yu Jue was to be the manager.

Educating Court Women

In the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising (1899–1901), Empress Dowager Cixi initiated a series of measures to reform the court and modify rulership. Among her reform efforts was a plan to establish a school to educate women of the noble Manchu clans with the aim of creating “roles for them in the inner workings of the central government.” Underlying this initiative was her intent to bolster her power and image both within the court and on the international stage. The concept for the school was based on Cixi’s own educational experience and foreign models of modern education for women in the early twentieth century. Japan’s new female education was the ultimate model for Cixi, not only because the Japanese valued the view of “good wives and wise mothers” in accord with Chinese traditional morality but also because her goal of grooming noblewomen for governmental roles echoed the Meiji emperor’s rethinking of the positions nobility played in the government. Cixi further expanded the notion of nobility to include women from elite families, such as the daughters of high-ranking officials, with the aim of educating them to participate in a modern bureaucracy in which women contributed to supporting reforms of the newly conceptualized monarchy. Her admiration for the new female education in Japan was demonstrated by her desire to have an audience with Japanese educator Shimoda Utako (1854–1936); regrettably, Cixi died before the event was to take place.

Although Cixi’s vision for the school was never fully realized, the establishment of the Embroidery Program for Women and the appointment of Shen as its principal instructor demonstrated Cixi’s support of female education and recognition of women artists. Shen was not the first female artist Cixi employed in her court. Following the practice of previous emperors who appointed court painters during their reigns, Cixi appointed a number of court painters, some of whom were women, including Miao Jiahui (1841–1918) who would frequently ghost-paint or write calligraphy for Cixi. The empress dowager also commissioned sets of porcelain ware named “Daya zhai” between the years 1907 and 1908. Ying-chen Peng argues that Cixi’s commissioning of the arts was a means of legitimizing and consolidating her regency and authority. The arrival of Shen’s embroidery at the court was a timely affair, as Cixi had recently issued an edict to establish a bureau of women’s work (Nügongyiju) to oversee the teaching of female nobles, in part so that they could appreciate the difficulty of manual work. While the main focus of the program was on the less demanding skills such as weaving terrycloth and plain fabrics, Cixi was planning to hire skilled embroiderers from the Zhejiang region to teach fine embroidery. As the edict shows, Cixi specified embroiderers from a region where Suzhou-style embroidery was practiced, indicating her predilection for that style of work. It is also possible that she already had Shen Shou in mind as the chief instructor when the edict was issued. Cixi was known to have been personally involved in the design of embroidered patterns on her robes. She frequently gave instructions to the embroidery workshop (Xiuhuochu) for the design and production of her robes. Appointing Shen to the court could have been in Cixi’s plans to serve her own interest; however, it foreshadowed the curriculum of the new public education program for women sanctioned in 1907, of which women’s work (nügong ) was an important component.

When the Embroidery Program was established, it fell under the purview of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce, a government body established in 1906 by combining the Ministry of Commerce with the two bodies that oversaw agriculture and industry. With Prince Zaizhen at its head, the ministry established a number of bureaus to promote the development of various industries, including one overseeing the arts and crafts (gongyi) sector. As the program was established under a government body that managed industrial growth, Shen was therefore entrusted with the responsibility to not only train women embroiderers, but also to modernize and advance traditional nügong for the state. The move redefined the traditional virtue of embroidery to recognize it as a livelihood for women and simultaneously emphasized its economic value for the state, a position that was borne out by Shen’s trip to Japan.

Learning about the West via the East

Before Shen started her job as the chief instructor in the fifth lunar month of 1906, the ministry sent her, along with her husband, to Japan to survey the country’s revamped ornamental textile industry and its programs for training female embroiderers. In the mid-nineteenth century, embroidery and lace from China were in high demand in Europe and the United States. At the end of the nineteenth century, however, China’s embroidery and other silk products were facing stiff competition from Japanese products on Euro-American markets. One of the most significant tactics used by the Japanese decorative textile industry to gain a larger share of the foreign market was the adoption of subject matter and techniques from Western art sources, which were then rearticulated into new motifs and expressions. Whereas Chinese embroiderers were still producing works featuring landscapes, figures from folk tales, and flower-and-bird designs based on traditional Chinese motifs, Japanese embroidery captivated Euro-American customers with its vibrant colors, realism, and familiar and yet exotic subject matter.

During their three-month trip, which lasted from the eleventh lunar month of 1905 to the second lunar month of 1906, Shen and her husband visited a number of workshops, retail shops, and public and private embroidery schools for women in Kyoto, Tokyo, Kobe, and Nagasaki.38 Shen was enlightened by the new-style embroidery that the Japanese called “artistic embroidery” (meishu xiu; Jp. bijutsu shishu) and discovered the concept of form-likeness in these works that she later applied in her “lifelike embroidery.” The term bijutsu is a translation of the European concept of “fine arts.” This nomenclature, used in the Japanese language to denote the study of art and aesthetics as a new academic discipline, was used with the awareness that in the Euro-American framework, fine arts were superior to applied arts, and that painting was regarded as the pinnacle of the hierarchy. Designating embroidery with the term bijutsu was therefore intended to elevate the craft to a form of high art with the hope of increasing the value of the work. This idea had a significant influence on Shen’s choice of subject matter in her new work.

You must be logged in to post a comment.