In few countries is the contrast between buried riches and visible squalor as great as in Afghanistan. Ancient towns like Balkh and Ghazna present scenes of desolation which belie the wonderful objects and architectural elements that archaeologists have recovered from them. Other rich sites, like Ai Khanum, lie below the surface of a featureless plain. Perhaps only Herat recalls to visitors the storied riches of this country, with its grandiose mosque and Sufi shrines. It is in a way surprising that Afghanistan attracted so many archaeological missions, though after the fact they were well rewarded for their efforts. In Ancient Civilizations of Afghanistan, Warwick Ball recounts how Afghanistan has historically been the center of many civilizations, and not the isolated, peripheral land it has become.

Afghanistan lies in the centre of Asia. We should never have been surprised by its hosting great civilizations on its territory. Yet in the eyes of early archaeologists, the country simply participated by procuration in the great adventures of Iranian civilization, Indian civilization, or even Chinese. The more we learn about Central Asia, the more we recognize its originality and creativity. Many elements we identify as Iranian came from Afghanistan, including circular cities, and Zoroastrianism. We are beginning to see the Oxus civilization as a major link between Harappa and Elam. Being in the center means being an essential link in trade, ideas and art—and this accounts for the richness of Afghanistan’s archeological records.

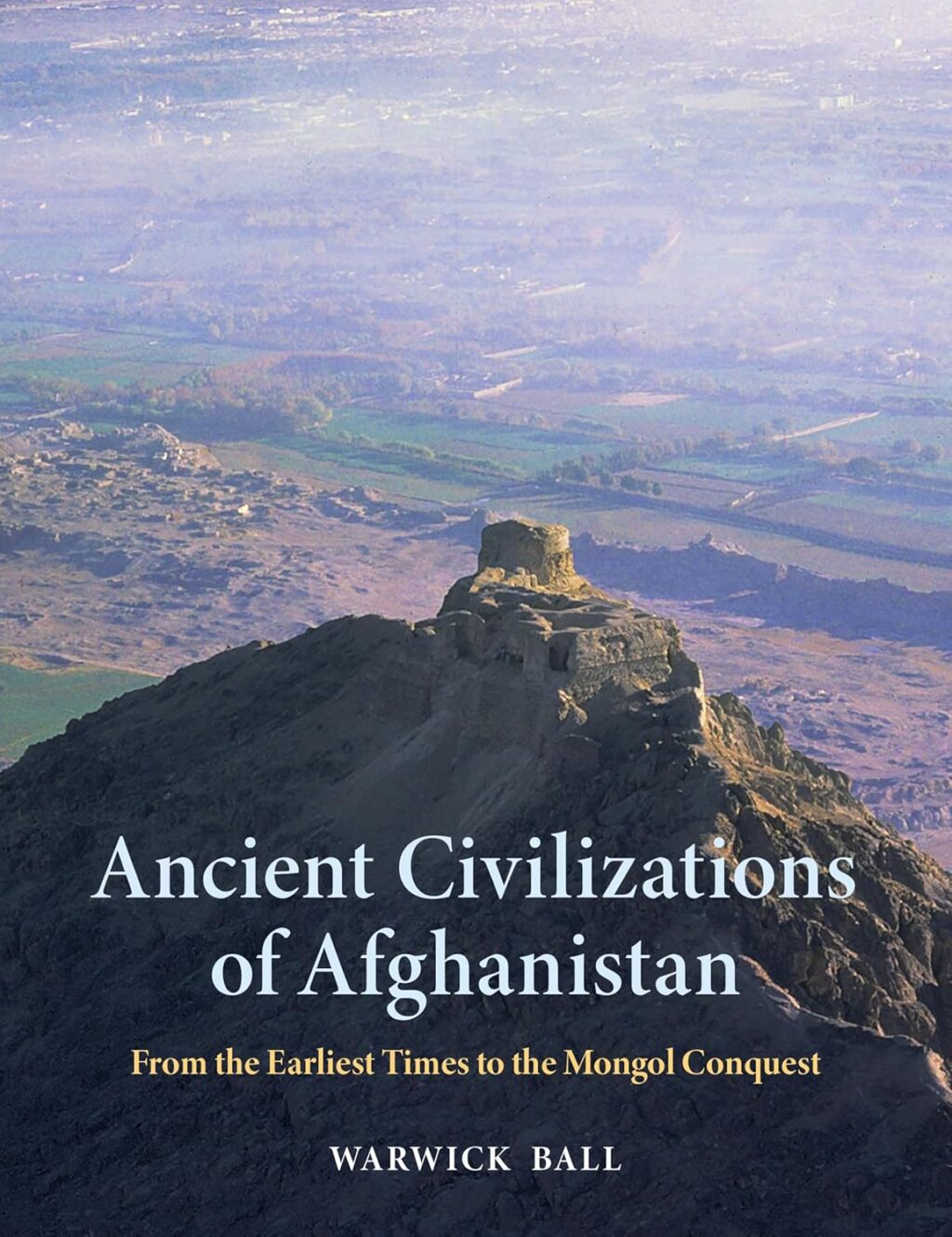

The quality of the photographs is outstanding.

The story of archeology in Afghanistan, retold here, encapsulates this reimagining of the country from a peripheral to central one. The first European to investigate Afghanistan’s past, Charles Masson, set out to find traces of Alexander the Great. Subsequent missions continued to search for Hellenistic sites, showing a distinctly Eurocentric and even imperialist bias. Japanese scholars, on the other hand, concentrated on Buddhist sites, with links to the Indian subcontinent. People called Afghanistan the crossroads of Asia, like a market where you could buy goods from anywhere (and for decades you could indeed buy Greek coins and Buddha heads in the bazaar).

It would be a mistake, however, to see the Greeks of Afghanistan as mere outposts of Hellenism. They worshipped local gods, unknown in Olympus, and later became enthusiastic Buddhists. They created the distinctive art of Gandhara, the first to represent the Buddha in human form. Later, under the Kushans, Afghanistan became the center of world Buddhism. This dynasty, of steppe origin, ruled an empire roughly corresponding to the Afghan empire of Ahmad Shah in the 18th century. Their very existence was lost to history for centuries, which partly explains why we struggled to see Afghanistan as home to a distinctive civilization.

We also should be on guard against the Spenglerian notion that civilizations are in any way hermetic. Ball notes the uncanny Roman echoes of Gandhara sculpture—directly or indirectly, Rome and Afghanistan engaged in a dialogue. Similarly, the faces painted in caves by Central Asia Buddhists resurface in 13th century Persian book illustrations. Techniques, then and now, travel.

Ball belongs to the peaceful migration school that tends to downplay the role played by violent invasion. Elsewhere this school is in retreat, as DNA studies confirm massive and sudden replacement of one people by another. DNA is not addressed in the current book, so we cannot confirm or infirm Ball’s position. It is certainly the case that even if there have been violent invasions by different groups, Scythians, Kushans, Huns, and Mongols, there is a civilizational pull of gravity that preserves art and ways of life across political regimes. Even Islam, Ball reminds us, did not displace Buddhism as the major religion of Afghanistan until 500 years after this allegedly hegemonic religion first entered the country.

The civilizational gravity Ball explores revolves primarily around architecture, and the ruins thereof, reflecting the author’s perspective as an archaeologist. He makes a convincing case for unique and persistent patterns of design that characterize first millennium CE monuments, finishing the book with a demonstration of ancient pattern persistence in the early Medieval period of the Ghaznavids and the Ghurids. This provides provocative insight into the styles of these great builders.

Ball’s narration is workmanlike, though occasionally punctuated by pedestrian observations and suffers from redundancy. He assumes that the reader knows little about Afghanistan, providing much background information on ethnicity and geography. His section on the history of archaeology provides a good overview, though he lacks charity in some of his judgements. The quality of the photographs is outstanding—and will be the main reason why people will buy this attractively printed book. Readers of French may want to complement their reading with Bernard Dupaigne’s Afghanistan, monuments millenaire (2025 actes sud).