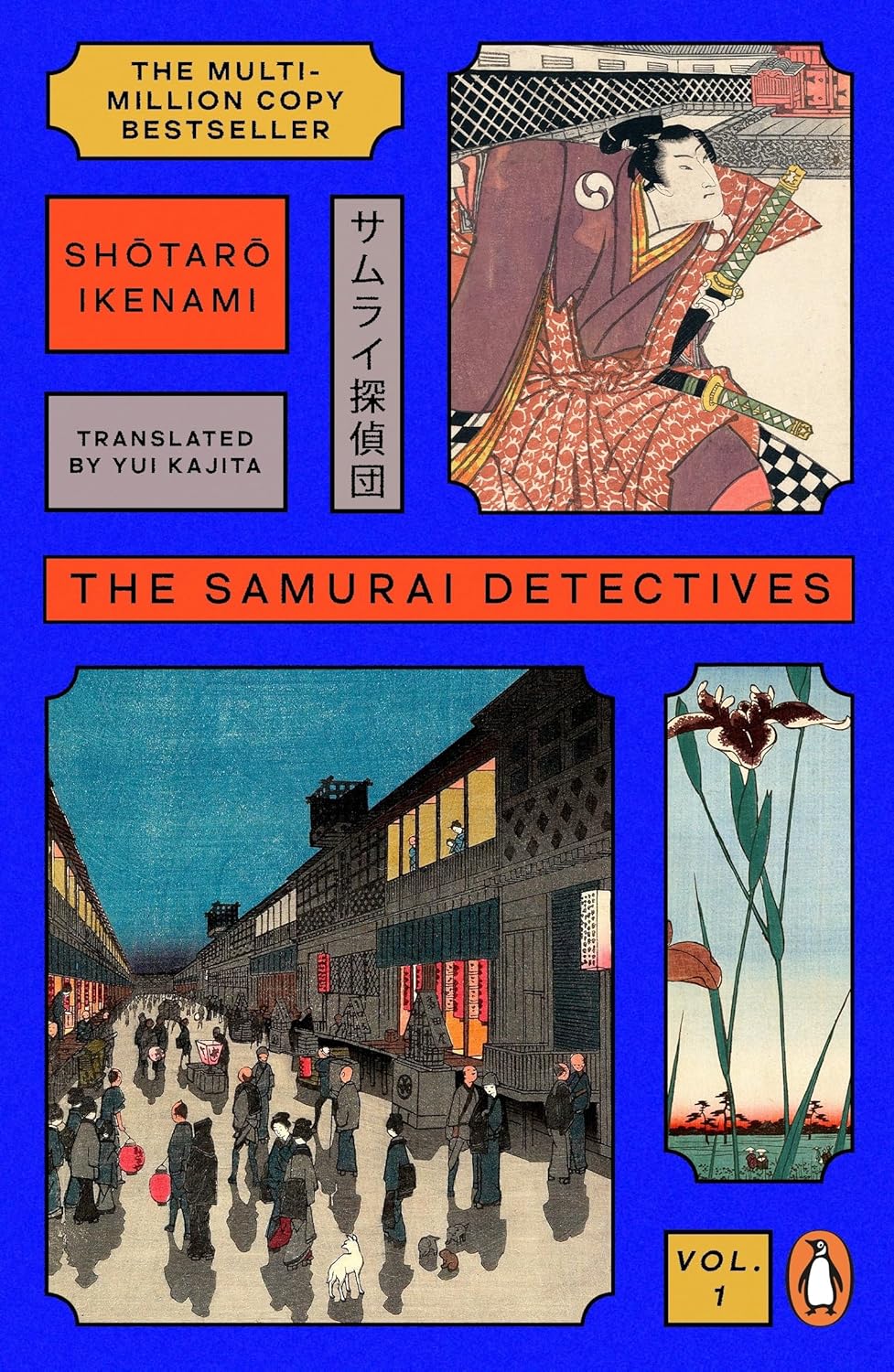

Shōtarō Ikenami’s The Samurai Detectives, the first volume in his celebrated Kenkaku Shōbai series, arrives in English translation byYui Kajita as a lively entry into Japanese historical fiction. Originally published in 1973, this novel captures the shadowy underbelly of Edo-period Japan through the eyes of Kohei, a grizzled ronin turned detective, his 24-year-old son, Daijiro, and an enigmatic swordswoman, Mifuyu. Set against the rigid social order of the Tokugawa shogunate, the story unfolds as a series of episodic cases involving assassinations, lost swords, and illicit love in the bustling capital of Edo (modern Tokyo). Ikenami, a titan of the genre whose prize-winning works sold millions, crafts vivid tales of samurai life that have inspired over a dozen films and TV adaptations.

The historical backdrop anchors the novel firmly in the Edo era (1603-1867), a 264-year stretch of enforced peace after centuries of civil war. Founded by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the shogunate centralised power under the shogun in Edo, while the emperor remained a ceremonial figure in Kyoto. This military government stabilized Japan through strict controls, including the sankin kōtai system that kept daimyo—feudal lords—at court half the year to curb rebellion. Prosperity followed, with economic growth in rice-based trade, but so did stagnation. Samurai, once warriors, became bureaucrats or wanderers, their lives measured in koku, the rice yield needed to feed one person annually (about 150 kilograms). A daimyo’s domain required at least 10,000 koku, while a greater hatamoto—a direct shogunal vassal—earned 1,200 to 10,000 koku.

The Samurai Detectives unfoldings as a series of episodic mysteries tackled by a trio of samurai in Edo.

The Samurai Detectives lacks a single, overarching central plot, instead unfolding as a series of episodic mysteries tackled by the trio of Kohei, Daijiro, and Mifuyu in Edo. Each of the seven chapters—”The Swordswoman”, “The Oath of the Sword”, “The New Geisha”, “The Four Rulers of Izeki Dojo”, “River Suzuka in the Rain”, “Kinchan of the Painted Brows”, and “Assassination by Poison”—presents a stand-alone case for the samurai to solve, ranging from stolen blades and dojo rivalries to poisonings and geisha espionage.

The catalyzing incident of the book occurs in “The Swordswoman” and binds the trio when Kohei rescues Mifuyu from an ambush, revealing her skill and defiance of a political marriage, prompting them to team up with Daijiro to investigate a disgraced samurai’s stolen sword. While a loose thread of fighting corruption ties their efforts, the novel prioritizes atmospheric vignettes and cultural texture over a cohesive, linear narrative, a style akin to Japanese genre fiction that mirrors the meandering investigations in period films like those of Akira Kurosawa.

The narrative can feel bogged down by a multiplicity of characters—dozens of samurai, informants, and schemers whose names and alliances blur across chapters. But what surprises most is the novel’s bold undercurrents, rare in patriarchal Edo tales. Mifuyu is an empowered swordswoman who defies norms by mastering the blade with lethal finesse. At times disguised as a man, she infiltrates male-dominated spaces, her skills rivaling any male ronin’s. Her story challenges the era’s gender confines, yet Ikenami portrays her not as a novelty but a force, wielding a tanto dagger with the precision of a highly skilled adept. Even more striking is the implied homosexual bond between an ailing samurai and his devoted disciple. While such relationships were accepted as part of samurai tradition, that a novel from the mid-20th century should hint at the custom comes as a surprise.

Readers who are accustomed to tightly-plotted period pieces such as James Clavell’s Shogun or Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series may find The Samurai Detectives slow-moving, while Japanophiles and those familiar with the region’s literary quirks will savour Ikenami’s immersive and non-linear style.