Sixth-grader Lina Uesugi received a strange set of instructions from her father before the beginning of summer vacation: “Go to the Misty Valley. There’s a person there who was good to me years ago.” He didn’t explain to her why she should go or what will happen when she arrives. He simply put her on a train from Shizuoka Prefecture, about 145 kilometers (90 miles) down Japan’s eastern coast from Tokyo, to head north and inland.

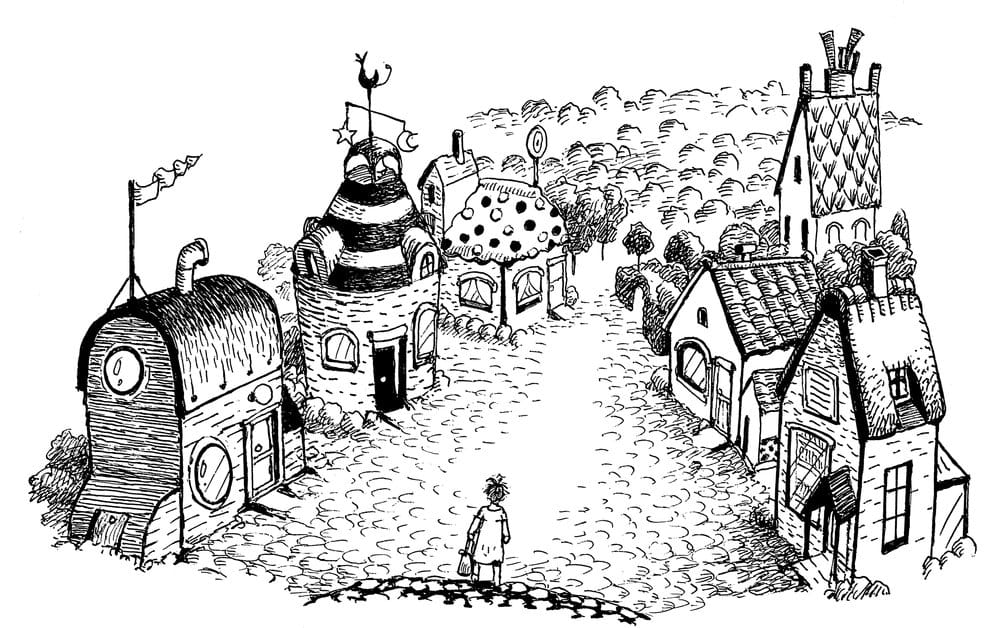

When Sachiko Kashiwaba’s middle-grade The Village Beyond the Mist opens, Lina waits at an abandoned rural train platform—and no one at this out-of-the-way station knows where the Misty Valley is! After a series of small misadventures, Lina finally makes her way to her destination: “This is definitely not a normal mountain village,” she notes.

Lina soon finds herself living at Picotto Hall, an odd boarding house where she’ll be expected to earn her own keep. The strange, crotchety landlady, Ms Pippity Picotto, reminds her that “He who does not work shall not eat.”

“But I don’t have any work skills,” Lina has the self-knowledge to reply. After all,

Her handwriting was messy, and she was all thumbs with the abacus. Her days were filled with school and cram school, so she never had time for chores at home. She didn’t know how to do laundry or cook. She had learned to plan and budget for a meal, but actually making food taste delicious was beyond her.

The landlady responds, “You have arms and legs, don’t you? You have eyes, a nose, ears—from the look of you, everything’s in working order! Who told you that you have no skills?”

Lina eventually meets and befriends the other residents of Picotto hall—the inventor Icchan, the chef John, and an enormous golden cat named Gentleman. Over the course of her stay in the Misty Valley, she works at a series of businesses in the mountain village along what the residents call Absurd Avenue. Lina is the only resident of Absurd Avenue who isn’t descended from sorcerers, and there’s a little bit of magic behind every door Lina opens.

The Village Beyond the Mist is an episodic coming-of-age tale. Lina progresses from job to job, learning about herself and her world, becoming a better, more capable person along the way. Much like Eiko Kadono’s Kiki’s Delivery Service, published about a decade later and most recently translated into English by Emily Balistrieri, the magic isn’t really the point of the story—the magic only provides a set-up for Lina to grow. (In many ways, The Village Beyond the Mist bears a strong resemblance to realistic children’s classics like Anne of Green Gables, a book as well-loved in Japan as it is in the English-speaking world and that Lina happily recognizes encounters in Absurd Avenue’s bookshop.) By working in a kitchen and an inventor’s workshop, in a bookstore, a nautical goods store, and a toy store, Lina learns not only how to cook and clean, but also how to be attentive to other people’s needs and observant of the world around her.

Kashiwaba’s intended audience might also be grateful to note she doesn’t place all of the responsibility for Lina’s faults on Lina herself—and that there’s a lesson here for parents, too. Lina hasn’t done chores because she hasn’t been asked to and she hasn’t chosen her own clothes because her mother has made those decisions for her. On Absurd Avenue, Lina begins to come into her own. Later, she helps a spoiled young prince learn to do his own labor, too. When he explains that Lina is the only one who will “order [him] around or stand up to [him]”, Lina softens.

“You’re not the only one to blame, then,” she says. “That’s how your world works. I didn’t realize that when I was criticizing you.”

Some elements of the plot of The Village Beyond the Mist might sound familiar to readers who have watched Hayao Miyazaki’s celebrated anime film Spirited Away. Miyazaki was actually in talks to acquire Kashiwaba’s novel before he began work on his seminal film. Although the stories have little in common narratively, they both star a spoiled little girl who arrives in a new, magical place who must learn the value of hard work.

Kashiwaba’s then-illustrator, Takakawa Kozaburo, accused Miyazaki of plagiarism. (Some of the character designs, particularly of grumpy witches in both stories, bear a surface resemblance to one another.) Kashiwaba’s publisher dropped Kozaburo, but began describing Kashiwaba’s story as the “inspiration” for Spirited Away in some printed editions of the book. Advertising copy for the English-language edition, too, notes that The Village Beyond the Mist is “the fantastic adventure that first inspired Hayao Miyazaki’s beloved film.” Both parties seem to accept this compromise—that there is clearly some thematic overlap, but not an overlap that rises to the level of “plagiarism”. Kozaburo’s illustrations no longer decorate Kashiwaba’s novel; delightful pictures by Miho Satake compliment the English-language edition, instead.

The Village Beyond the Mist might seem unfamiliar to readers of Kashiwaba’s other novels available in English, both, like The Village Beyond the Mist, also translated by Avery Fischer Udagawa. Both Temple Alley Summer and The House of the Lost on the Cape are thematically darker stories. Temple Alley Summer is about a fifth-grade boy trying to save his newly-resurrected ghost friend from being banished back to the land of the dead; coincidentally published shortly after the March 2011 Triple Disasters, the children’s novel about death by an author from Tohoku, the region most affected, turned out to be a touchpoint for children grieving after the earthquake, typhoon, and nuclear disaster. The House of the Lost responded more directly to 3/11, telling the story of a woman, a girl, and a mysterious granny who become a family after meeting at an emergency shelter in the fictional city of Kitsunezaki. In the novel’s truly horrifying climax, a monster impersonates the loved ones Kitsunezaki’s residents most miss or fear. The döppelgangers tell the townspeople that “having dreams for the future doesn’t make sense” in a town like theirs—and tempt them to throw themselves in the sea. Both novels are serious meditations on the meaning of death and what makes life worth living, presented through narratives appropriate for their middle grade audiences.

It’s one of the odd exigencies of reading in translation that an author’s books don’t always “arrive” in a new language in publication order. It isn’t surprising that The Village Beyond the Mist is lighter and also thematically less sophisticated than Temple Alley Summer and The House of the Lost. Kashiwaba published The Village Beyond the Mist, her debut, in 1975, when she was in her early 20s; Temple Alley Summer was published in Japan in 2011 (translated into English in 2021) and The House of the Lost on the Cape was serially published from 2014-15 (translated into English in 2023). In her original 1975 afterword to The Village Beyond the Mist, Kashiwaba talks about the influence of PL Travers’s Mary Poppins and CS Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. (You can learn more about Japanese literature, author Sachiko Kashiwaba, and her novel Temple Alley Summer with the Read Japanese Literature podcasts’s episode Japanese Children’s Literature—transcript available). Her much later novels add the influence of a lifetime of experience as both a writer and a human being.

With a simpler story, The Village Beyond the Mist has a charm of its own. In that same 1975 afterward, Kashiwaba describes her recent insight that she had come to see that the sorts of magical characters she encountered in the world of Mary Poppins or in Narnia live in the real world, too. That’s really what the novel is about—that the world is magical for people who know how to look, and that’s ultimately what Lina is on Absurd Avenue to learn how to do.

Some of the most enchanting elements of Temple Alley Summer and The House of the Lost are even more on display in The Village Beyond the Mist, notably a playful narrative voice and a lighthearted tone—in the case of her later work, the gentle tone, even when serious issues are central to the story, are what keep Kashiwaba’s work securely in the realm of middle grade fiction. Translator Avery Fischer Udagawa also brings the same charming, light-handed touch to The Village Beyond the Mist that she did to Kashiwaba’s other work. Her translations present a blend of the familiar and the new. They leave just enough Japanese terms (katakana, Kiyomizu and Shino ware, kendama toy) unexplained for the reader to explore on her own. Elsewhere, Satake’s illustrations serve as a visual glossary, such as a picture of a little boy who refuses to take off his Hyottoko mask—a mask of a comical Japanese stock character with a mouth wryly cocked to one side.

Toward the end of the story, Lina discovers an hedge of azaleas she can access by taking an out of the way route to work. She considers it “another wonder of Absurd Avenue”. And if The Village Beyond the Mist has a lesson, it’s this: those wonders, the delight in the mundane, is available to anyone who looks. Moving through the azaleas, Lina starts her day “full of the joy that comes from seeing something unexpected and beautiful.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.