A Swiss-Italian-Spanish author fluent in six languages (including English), Vanessa Fabiano first traveled to China more than thirty years ago and resided in Shanghai and Beijing around the time of SARS in the early 2000s. Her new collection of related stories, Chinese on the Beach, makes use of this timeframe, a period of growing friendships between Chinese and foreigners.

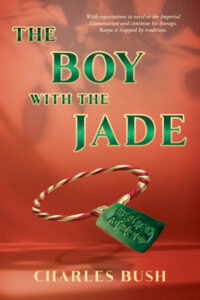

In 18th-century China, young aristocrat Baoyu—born with a jade pendant foretelling his fate—grapples with love, loss, and identity amid the grandeur and constraints of his powerful family. Torn between his cousin Daiyu and his devoted maid Amber, Baoyu’s privileged world unravels through tragedy, betrayal, and the crushing weight of expectation. Seeking freedom from duty and despair, he embarks on a spiritual quest shaped by Taoist and Buddhist wisdom.

In Silk Roads, food writer Anna Ansari connects areas and cuisines not typically associated in English-language cookbooks, traveling from Beijing, to Baku in Azerbaijan. The closest author/chronicler would perhaps be Paula Wolfert, who is known for her Mediterranean cookbooks spanning France, Morocco, and the “eastern Mediterranean” to include Turkey. Ansari’s food memories originate from her ethnically Turkish family who left Iran and settled in the US.

Arundhati Roy’s much-awaited memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me, tackles Roy’s writing career, India’s sweeping political instability, and most of all, a reckoning with an exhilarating character: her mother, Mary Roy. From Roy’s village, fictionalised even here as “Ayemenem”, to the chaotic urban sprawl of Delhi, the book covers Roy’s rocky childhood, her brief architectural foray, her sudden and dizzying literary stardom, and eventually, her settling into the role as one of India’s most beloved—and most widely politicised—writers.

Our beliefs about the past pass through filters both ideological and physical. Cotton, leather and papyrus all disintegrate with time, but fired clay does not. Hence museums filled with jugs and bowls instead of scrolls and clothing. Still, such a vessel inspired one of England’s most celebrated poems, John Keat’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”. It seems that Fahad Bishara had a similar epiphany when he beheld a century-old ship’s logbook, or ruznamah. Although written in prose, Monsoon Voyagers evokes Keats by bringing a lost world to life, combining a scholar’s rigor with a poet’s voice.

Begum Wilayat Mahal, the self-proclaimed heir to the House of Awadh, has fascinated journalists and writers for decades. She claimed she was Indian royalty, descended from the kings of Awadh, a kingdom annexed by the British in 1856. She spent a decade in the waiting room of the New Delhi train station, receiving journalists intrigued by the image of Indian royals in cramped conditions. Then, her family was granted use of a rundown 14th-century hunting lodge in Delhi; none were seen in public again.

Author and activist Sarah Joseph was born and raised in present-day Kerala, known for both Jewish and Christian populations dating back well into the first millennium CE. A Christian herself, she writes both poetry and prose in Malayalam, often centering around religion and feminism. A decade ago she won accolades for a novel based on the Ramayana. Now she has a new novel, Stain, translated by Sangeetha Sreenivasan, that re-imagines the biblical story of Lot, largely set in the town of Sodom. Although readers of the English translation will undoubtedly be familiar with the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, one would have to assume that Joseph’s original Malayalam audience either also know the story or find resonance in a biblical story set long ago and far away.

Think of Cold War communist insurgency and guerilla warfare might well spring to mind. Sometimes it worked, building from the hinterlands to capture the capital: see Cuba. Sometimes it failed: see Che in Bolivia. And sometimes the revolutionaries remained stuck in the wild, undefeated but unable to seize the state.

That translator Dong Li calls Chinese poet Ye Hui “metaphysical” in his introduction to The Ruins—a characterisation repeated in the book’s marketing material—might seem challenging, but in the fact the poems, while not exactly straightforward or immediately obvious, are—for most part—eminently accessible and interesting.

A nascent media mogul battling for political survival, a love triangle fractured by the SARS pandemic, the ruthless choreography of Shanghai’s social scene—each story in Chinese on the Beach explores the particular madness of living through history, when old rules dissolved overnight and new ones hadn’t yet formed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.