Our beliefs about the past pass through filters both ideological and physical. Cotton, leather and papyrus all disintegrate with time, but fired clay does not. Hence museums filled with jugs and bowls instead of scrolls and clothing. Still, such a vessel inspired one of England’s most celebrated poems, John Keat’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”. It seems that Fahad Bishara had a similar epiphany when he beheld a century-old ship’s logbook, or ruznamah. Although written in prose, Monsoon Voyagers evokes Keats by bringing a lost world to life, combining a scholar’s rigor with a poet’s voice.

Begum Wilayat Mahal, the self-proclaimed heir to the House of Awadh, has fascinated journalists and writers for decades. She claimed she was Indian royalty, descended from the kings of Awadh, a kingdom annexed by the British in 1856. She spent a decade in the waiting room of the New Delhi train station, receiving journalists intrigued by the image of Indian royals in cramped conditions. Then, her family was granted use of a rundown 14th-century hunting lodge in Delhi; none were seen in public again.

Author and activist Sarah Joseph was born and raised in present-day Kerala, known for both Jewish and Christian populations dating back well into the first millennium CE. A Christian herself, she writes both poetry and prose in Malayalam, often centering around religion and feminism. A decade ago she won accolades for a novel based on the Ramayana. Now she has a new novel, Stain, translated by Sangeetha Sreenivasan, that re-imagines the biblical story of Lot, largely set in the town of Sodom. Although readers of the English translation will undoubtedly be familiar with the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, one would have to assume that Joseph’s original Malayalam audience either also know the story or find resonance in a biblical story set long ago and far away.

Think of Cold War communist insurgency and guerilla warfare might well spring to mind. Sometimes it worked, building from the hinterlands to capture the capital: see Cuba. Sometimes it failed: see Che in Bolivia. And sometimes the revolutionaries remained stuck in the wild, undefeated but unable to seize the state.

That translator Dong Li calls Chinese poet Ye Hui “metaphysical” in his introduction to The Ruins—a characterisation repeated in the book’s marketing material—might seem challenging, but in the fact the poems, while not exactly straightforward or immediately obvious, are—for most part—eminently accessible and interesting.

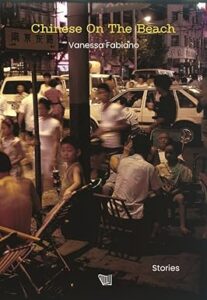

A nascent media mogul battling for political survival, a love triangle fractured by the SARS pandemic, the ruthless choreography of Shanghai’s social scene—each story in Chinese on the Beach explores the particular madness of living through history, when old rules dissolved overnight and new ones hadn’t yet formed.

Malay folklore is peopled—if that’s the right word—with a variety of supernatural beings, ghosts, and spirits, which reflect cultural anxieties, historical beliefs, and the blending of animistic traditions with Islamic, Indian and Chinese influences. Given this tradition has been a fundamental part of local storytelling for centuries, it’s unsurprising that horror is a staple of the Malaysian film and publishing industries. Malay-language horror movies often outperform Hollywood blockbusters in the domestic market, and locally published horror fiction is popular, in both English, and Malay.

In 1923, archaeologist Leonard Woolley stumbled upon a room that dated back to 530BC, the time of the Babylonians. Oddly, the room was filled with artifacts that were thousands of years older. A clay drum led Woolley to speculate that he might have stumbled across the world’s first museum.

Tipu Sultan, known as the “Tiger of Mysore”, ruled the southern Indian kingdom of Mysore from 1782 to 1799. Born in 1750 to Haidar Ali, a military leader who gained power through strategic alliances, Tipu inherited a strong state during colonial upheaval. He led Mysore to prominence, fighting the British East India Company in the Anglo-Mysore Wars, and died heroically in 1799 defending Srirangapatna. Tipu stood out for his innovations and controversies. He boosted the economy with silk and trade reforms, introduced a new calendar and coins, and developed iron-cased rockets that impressed British forces. He even sought alliances with Napoleon and the Ottoman Empire to counter British rule. However, his legacy splits opinion: hailed as an anti-colonial hero, he’s also criticized for forcing conversions and destroying religious sites in Malabar and Kodagu, sparking debates over his tolerance versus tyranny.

In an epilogue to his new book Assassins and Templars, Steve Tibble says (or, perhaps, protests) that his book really has nothing to do with the video game “Assassin’s Creed”, that any similarity is not so much coincidence as common intellectual and cultural ancestry. Readers of a certain generation might entertain some skepticism, especially in light of Tibble’s colloquial (albeit steadfastly rigorous) approach to the subject. Tibble might nevertheless have been aware of some pop-culture competition for reader mind-space, for he has written a page-turner of a history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.