Set in Singapore, Vancouver, London, and the spaces in between, the short stories in Heaven Has Eyes offer an imaginative, penetrating look at the complexities of migration, belonging, and a desire to find a home in the world.

Set in Singapore, Vancouver, London, and the spaces in between, the short stories in Heaven Has Eyes offer an imaginative, penetrating look at the complexities of migration, belonging, and a desire to find a home in the world.

Although Razia Sajjad Zaheer’s collection Darkness and Other Stories was written following India’s partition in 1947, it simmers with relevance today. Women still confront misogyny and sexism. They continue to be judged for their choices—sometimes by their own kind—and must often accept a lower social status.

Genpei Akasegawa (whose given name was Katsuhiko Akasegawa) was already famous as Neo-Dadaist artist when he began writing under the name of Katsuhiko Otsuji, and he soon proved himself able to work fruitfully in both domains, earning numerous awards. I Guess All We Have Is Freedom, beautifully translated by Matt Fargo, brings together five of Akasegawa’s short stories, some of them award winners, and all of which follow a narrator (presumably modeled on the author himself) through seemingly banal adventures as a father, professor, and denizen of Tokyo.

I was born in Bombay and lived there, not far from the Gateway of India, for the first sixteen years of my life. I left the city by the bay soon after turning sixteen. When I returned decades later, I barely recognised it. The city and I had both gone through dramatic changes in the interim. So it was with real anticipation that I picked up The Only City, an anthology of stories about the city of my birth, edited by Anindita Ghose.

Across fifty-odd flash stories (particularly short pieces of fiction) in The Woman Dies, Aoko Matsuda and translator Polly Barton lean into the weird, nitty-gritty world of womanhood. For the most part, there is no immediate throughline connecting the stories—and their rich inner worlds—to each other. Yet eventually, the lines blur enough for images of women, glittery face highlighter, and lingerie frills to appear, blending the stories into a sparkling collection. All the stories play a part in building Matsuda’s world, where girlhood is a state of mind that can never be outgrown; it is at once a curse and blessing, the only thing the world values and despises in equal measure.

V Vinicchayakul, the pen-name of Vinita Diteeyont, is prolific by any measure, reportedly with more than one hundred novels under her belt, many adapted for television and film. Only a very few have made it into English; had not she been championed by translator Lucy Srisuphapreeda, perhaps none would have been.

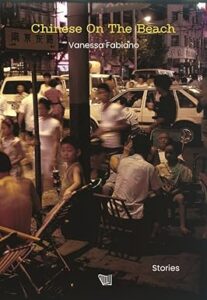

A Swiss-Italian-Spanish author fluent in six languages (including English), Vanessa Fabiano first traveled to China more than thirty years ago and resided in Shanghai and Beijing around the time of SARS in the early 2000s. Her new collection of related stories, Chinese on the Beach, makes use of this timeframe, a period of growing friendships between Chinese and foreigners.

Think of Cold War communist insurgency and guerilla warfare might well spring to mind. Sometimes it worked, building from the hinterlands to capture the capital: see Cuba. Sometimes it failed: see Che in Bolivia. And sometimes the revolutionaries remained stuck in the wild, undefeated but unable to seize the state.

A nascent media mogul battling for political survival, a love triangle fractured by the SARS pandemic, the ruthless choreography of Shanghai’s social scene—each story in Chinese on the Beach explores the particular madness of living through history, when old rules dissolved overnight and new ones hadn’t yet formed.

Written in the cursive-like Nastaliq script, and in an adaptation of Perso-Arabic alphabet, Urdu has become caught in religious silos. It “looks” Islamic, and therefore, in popular imagination, belongs to just one community in the multilingual universe. Anthologies of Urdu literature—in Urdu and in translation, especially in English—seem to have perpetuated this simplistic narrative of Urdu equals Islam by only Muslim authors in their collections. With the anthology Whose Urdu Is It Anyway?, Rakhshanda Jalil attempts to bring diversity to the scene by including only non-Muslim writers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.