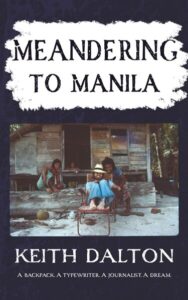

Keith Dalton was a journalist with foreign correspondent dreams. He had them as a 10-year-old. They never went away. Dalton was 25 when he crammed a typewriter in his backpack and set off from Australia to Southeast Asia, convinced he could be a self-made foreign correspondent. Writing as he went, Dalton took buses, trucks, trains, planes, passenger ferries, cargo ships, and canoes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.