What does it mean to be a historian? How do you try to explain the past when sources are lacking? And how do we talk about history when it’s so politicized? In the new book Speaking of History: Conversations about India’s Past and Present (India Allen Lane, 2025), Namit Arora and Romila Thapar discuss some of the challenges facing historians in India today, what it means to be an academic historian, and how ideas around gender, caste and religion may be getting distorted in India’s public history.

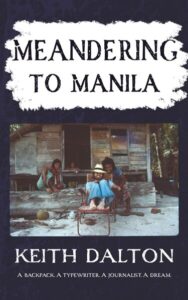

Keith Dalton was a journalist with foreign correspondent dreams. He had them as a 10-year-old. They never went away. Dalton was 25 when he crammed a typewriter in his backpack and set off from Australia to Southeast Asia, convinced he could be a self-made foreign correspondent. Writing as he went, Dalton took buses, trucks, trains, planes, passenger ferries, cargo ships, and canoes.

Jainism, an older contemporary of Buddhism, is rooted in the ideals of austerity. While Buddhism spread outside India, very little is known about Jainism worldwide. Similarly, in terms of art, it is subsumed within the larger Hindu and Buddhist traditions of rock-cut architecture. In terms of painting, the Kalpasutra and Uttaradhyaynasutra are two texts thought to date from at least 2000 years ago, have traditionally come with illustrations. However, beyond these examples, post-medieval Jain art has largely remained off the popular and scholarly radar. A recent set of essays looks at the ways in which this tradition developed new expressions.

In 1998, Ma Baoli, a closeted gay police officer living in Hebei, China, stumbled on the online novel Beijing Story while visiting an alleyway internet café. Deeply moved by its tale of gay romance, Ma’s life was changed forever, not just by the discovery of media made for gay men, but by the internet as a platform for media consumption and connection. Two decades later, Ma would be CEO of Blued, the “largest gay social networking app in the world.” But it wouldn’t last.

Set in Singapore, Vancouver, London, and the spaces in between, the short stories in Heaven Has Eyes offer an imaginative, penetrating look at the complexities of migration, belonging, and a desire to find a home in the world.

Ghosted: Delhi’s Haunted Monuments delves into the often-overlooked monuments of Delhi through the lens of jinns, Sufi saints and the horror tales associated with them, revealing both the brutality and humanity embedded in the collective history of the monuments and those who are tethered to them. Historian Eric Chopra contends that “to make sense of its antiquity is an overwhelming process for it’s a city that has witnessed 100,000 years of presence” and that in the light of the city’s long exposure to invasion and migration it “must be haunted”.

In a dark alley in Oxford, Yohan finds his mentor Doha Kim stabbed. With moments left to live, Doha tells Yohan that he must go to the Soju Club and meet with Dr Ryu. These are the North Korean spymaster’s final instructions, which Yohan knows he must obey.

Robert Strange McNamara was arguably one of the worst public servants in post-World War II American history. Decades after the Vietnam War ended, McNamara, who served as US Defense Secretary in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, admitted that as early as 1965 he believed that the United States could not win that war yet he orchestrated and publicly supported the Americanization of the war, sending more than 500,000 American servicemen to fight in what he believed was a hopeless cause. All the while, he kept telling the American people that the US was winning, even as he quietly recommended bombing pauses, troop ceilings, and negotiations with the North Vietnamese.

In 1924, the Republic of Turkey voted to abolish the Ottoman caliphate, ending a 400-year-long claim by the Ottomans that they were the leaders of the Islamic world. Abdülmecid II—who had been elected to the position by the Republic of Turkey just two years before—decamped for Europe.

Kay Enokido was the longtime president of the stately Hays-Adams hotel in Washington, DC, hosting dignitaries like the Japanese monarchy and the Obama family before the president was sworn in. But before she was a hotelier, and before that a journalist, she had another, earlier story, one that provides the heart of her book, Phantom Paradise: Escape from Manchuria.

You must be logged in to post a comment.