Even the idlest stroller will be awestruck by the beauty of Cairo’s City of the Dead. Yet this gem of 14th and 15th century architecture, a Unesco World Heritage site, leaves the visitor wondering about the sultans, beys and princesses for whom these elaborate monuments were built.. Stones can tell stories, but object can tell us even more. The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s exhibition, with over 250 pieces, aims to provide a fuller sense of these patrons, the Mamluks: who were they and how did they see themselves?

Paradoxically, the architectural marvels of Renaissance Cairo were built for military slaves, as the word mamluk signifies. The Mamluk themselves were usually simple pastoralists from the Kipchak steppe—what is now southern Russia. They spoke a branch of Turkic similar to that of the Tatars of modern Kazan. Raised in the saddle, they learned to shoot with bows and arrows from earliest childhood. Victims of tribal feuds and raids, many were kidnapped and then traded in Middle Eastern slave markets.

There, the brightest and strongest were recruited into elite slave regiments that formed the backbone of Islamic cavalry forces. These soldier-slaves received rigorous religious and cultural training. The most talented among them could rise to the highest ranks of government. Over time, such mamluks often overthrew their erstwhile masters and ruled in their own right. This dynamic unfolded across the Islamic world—where native elites gradually ceded sovereignty and military power to military slave castes. Mamluk regimes ruled in Delhi, Ghazna, and Khwarazm. Even in Baghdad, the caliph had become a figurehead for military slaves. When the Mongols sacked Baghdad and killed the caliph, one of his heirs escaped to Cairo, where he conferred religious legitimacy on Egypt’s Mamluk rulers. In this way, the Mamluks of Cairo acquired and protected both the 500 year-old caliphate and the even older cultural legacies of the Middle East, Iran and Central Asia.

Despite their violent demise, the Mamluks left behind a rich legacy.

The Louvre’s recent exhibition in Paris, The Mamluks, opened with what the French remember best: Napoleon’s victory over them at the Battle of the Pyramids. Although the exhibition, now in Abu Dhabi, covers the period until 1517, when the Ottomans officially ended the Mamluk Sultanate, Mamluk elites continued to rule Egypt as Ottoman vassals until 1811. That year, the new Ottoman governor, Muhammad Ali, famously invited the remaining Mamluks to a banquet—only to massacre them.

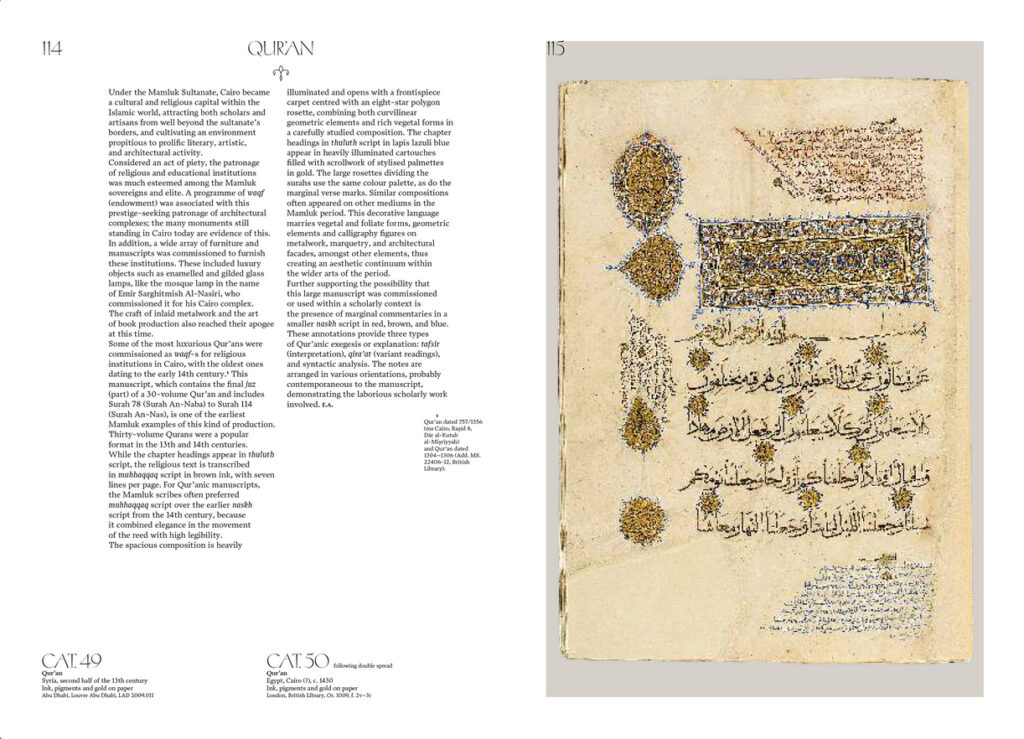

Despite their violent demise, the Mamluks left behind a rich legacy. Gallery-high photographs recall the wonders of Mamluk Cairo, including the Qalawan mosque and the City of the Dead. But what the city has largely lost is the beauty of intimate interiors, with its luxury objects and book arts. The exhibit fills this gap: here one sees how the Mamluks lived and how they celebrated themselves as protectors of the Faith.

Still, one must make an effort. The gallery’s dim lighting, meant to protect delicate manuscripts, can make it hard to appreciate many of the items on display. For this reason alone, the exhibition catalogue—with its high-quality reproductions—is indispensable. While the craftsmanship on display is undeniable, these objects can feel distant—reminders of a world of palaces, parade grounds, mosques, and madrasas far removed from our world. This is generally a problem in displaying Islamic arts: the absence of grand oil paintings and monumental sculpture makes it hard to get the heart pounding. Still, a few items stand out with such rarity and wonder that they invite the kind of awe a Venetian bailo might have felt on his first visit to Cairo or Damascus: a Turkish-Arabic dictionary written in a decorative patchwork of red and black ink—playful and instructive in equal measure, the gilded key to the Ka‘ba in Mecca, damascened in gold and silver, bearing the name of the sultan who restored the shrine; a volume of poetry with letters meticulously cut out of the paper—easily missed unless viewed closely, A delicate glass vase that gracefully imitates Ming porcelain; and an illustrated pilgrimage map created for Jewish travelers to the Holy Land.

These objects also reveal the strong cultural continuity between the Mamluks of Cairo and earlier Islamic dynasties. A hunting scene on a glass bowl echoes similar imagery from Seljuk-era ceramics. The Mamluks, like the Seljuks before them, patronized literature in Turkish and Persian. The exhibition includes an illustrated copy of Nezami’s Book of Alexander , and a dazzling wine glass decorated with the birds from Fariduddin Attar’s mystical poem—evoking not just Islamic spirituality but even the whimsy of Dr. Seuss.

The Mamluks also admired art from their adversaries, particularly the Mongol of Iran. One display features intertwining clouds and dragons on ceramics, textile, and glass works—visual evidence of Eastern, and even Chinese, influence.

The Mamluks saw themselves as guardians of centuries of Islamic civilization.

The exhibition’s culminating object is a spectacular brass basin once used to baptize several French princes, including the ill-fated Prince Imperial in 1856. Long assumed to be a medieval French artifact, later scholarship identified it as a Mamluk masterpiece. Though many such luxury objects bear inscriptions naming their patrons, this one does not. To help viewers appreciate its fine detail, the curators have included high-resolution magnifications of its decoration—a rare and welcome addition.

One only wishes the same treatment had been given to other objects in the show. The exhibition’s website offers glimpses of this, but nothing replaces the immersive experience of viewing these magnifications in person. These large images reveal an even deeper connection to Mongol and Iranian models, suggestive of the Great Mongol Shahname”.

The Mamluks saw themselves as guardians of centuries of Islamic civilization, ruling with a kind of enlightened despotism that would have appealed to Plato. The upstart Ottomans saw things differently. They conquered the Mamluks and carried many of their treasures to Istanbul, where they sought to re-create a cultural hegemony in a distinctly Ottoman style. As The Mamluks at the Louvre Abu Dhabi makes clear, however, much of what the Ottomans built was indebted to the splendor—and the legacy—of their rivals.

You must be logged in to post a comment.