The word miniature in fact comes from the Larin miniare or “to paint red”; early European miniatures—palm sized pieces that are parts of manuscripts and books facing a verse or an intense moment in a story or placed behind one—were initially delineated in that pigment. There was an Asian tradition of such painting as well, with Indian examples including illustrations in such texts such as the 12th-century Gita Govinda and 15th-century Rasa Manjari (15th century), as well as a great many Mughal examples.

This tradition of working not just with the small format but also of illustrating existing texts and ideas has been kept alive by more than a few Indian artists: the rich embellishments of previous centuries became a part of modernism in India. Unlike the abstract nature of surrealism or expressionism (among several other movements) that Western modernism is characterized by, Indian art needs to be recognized for its experiments with its own past.

In Alchemy: Contemporary Indian Painting and Miniature Traditions, Geeti Sen analyses the work of some of these artists: Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951), Manjit Bawa (1941-2008), American emigre photographer and artist Waswo X Waswo (1953-) in collaboration with Rajasthani miniaturist R Vijay, and Nilima Sheikh (1945-). The “Alchemy” in the book’s title comes from Sen’s view that these artists transform the way miniature art ought to be understood: it is not a bygone tradition but has instead been reinvented by several artists in different ways.

The book reproduces many paintings by these artists: the selection is very rich thanks to the variety within the work of the artists, their themes, and the forms they experiment with. Sen’s essays about individual artists place the paintings being discussed within the larger body of the artists’ work.

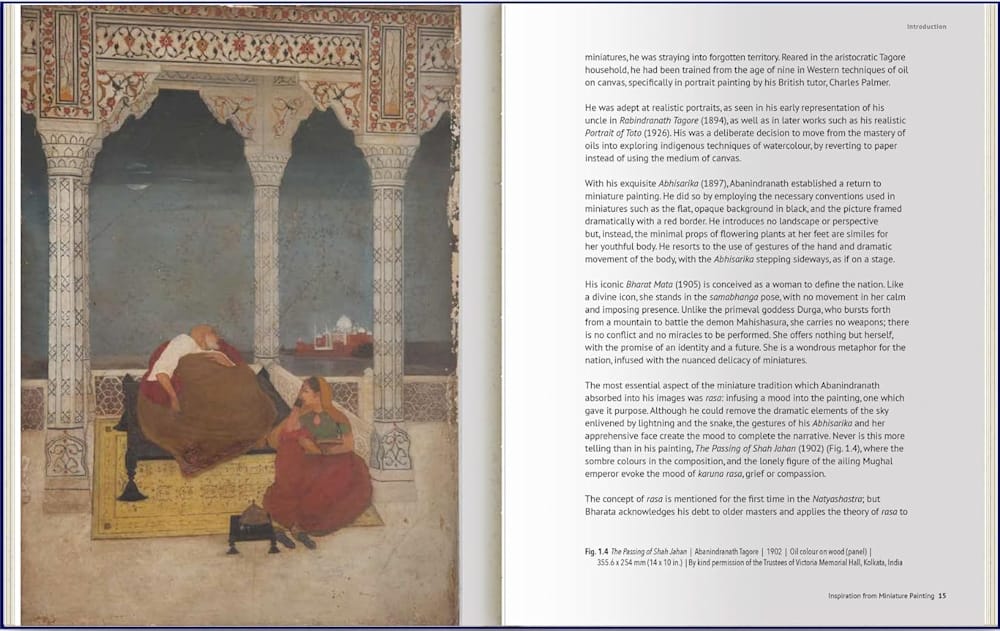

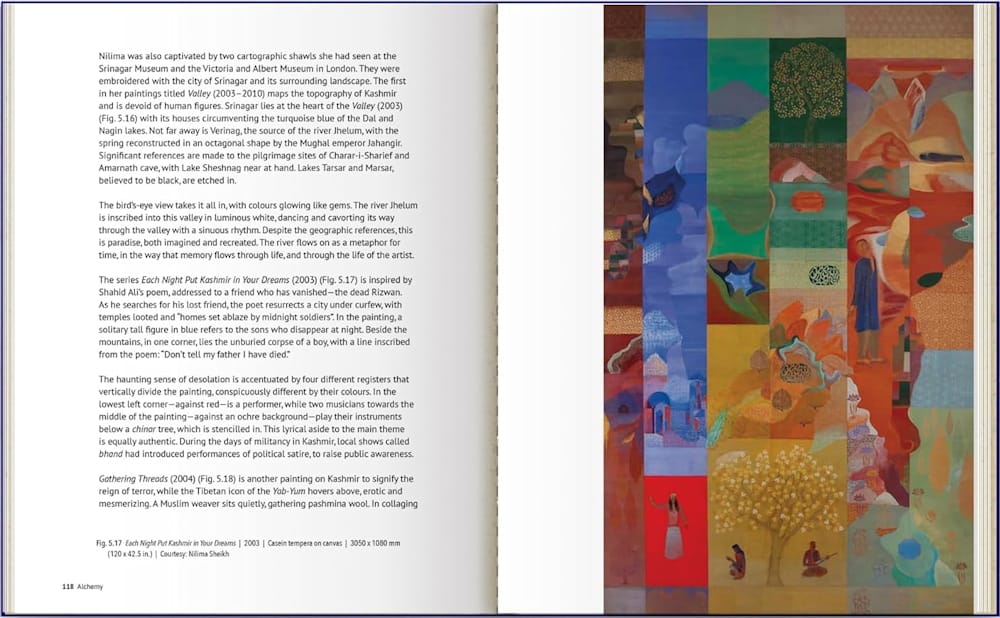

The story of each artist’s encounter with the miniature tradition is unique. While Abanindranath Tagore came to it after being compelled to unlearn his western training with the medium and encountering the “wash” technique from Japanese art, Manjit Bawa adopted the miniature because he was fascinated specifically by Lord Krishna’s childhood adventure and miracle stories (Krishna’s life as a whole, especially his youth and romance with Radha and the other gopis, has been the subject of miniature). On the other hand, the duo Waswo and Vijay intentionally pay tribute to the Rajasthani and Mughal masters while Nilima Sheikh experiments with tempera using traditional colors and paper.

Of all the artists, Tagore—also a theorist and scholar of Indian aesthetics—is probably the best known. While debated for its political meaning, Sen looks at his iconic Bharat Mata as an example of miniature as it was among the first works by him that was produced by the wash technique. One notices that the painting has a halo of sacredness without the goddess being shown with the usual attributes and iconography (a throne-vehicle, the gesture of blessing the viewer-devotee, weapons, specific markers of power, etc) because of the semi-transparent touch to what might otherwise look like a baffling image of an ascetic woman with a halo and four hands. The wash helps it acquire an other-worldly look, making one pause to think about Tagore’s title for the painting. India is a mother-goddess but she is unlike the heavily and loudly ornamentalized female divinities circulated in Indian visual culture. She is a goddess of simplicity.

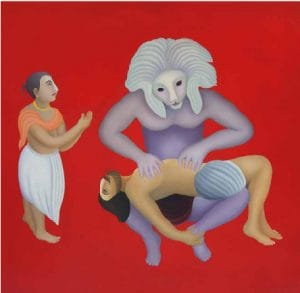

Similar examples from the other featured artists further illustrate this “alchemy”. Apart from Tagore’s Bharat Mata, one can turn to Manjit Bawa’s portrayal of gods and goddesses for highly non-ornamental depictions of divinities. His Narasimha Slays the Demon Hiranyakasipu shows Krishna in the avatar of Narsimha, half human and half lion, killing the demon to help the world get rid of evil. It is the simplest version of what could have been an elaborate depiction of the grand moment. It has been painted with very few colors; the scene is shorn of the background details showing only the god, the demon, and a witness. Bawa is known to have said:

[…] the advantage of the mythology is that you don’t have to complete the details. They are already known to the viewer; so you concentrate on the form, the colour, the space. You don’t want to become the slave of the narrative!

He keeps the bright red in the background, using much softer colors for the characters. The miniature aspect of his work lies not in its size perhaps but in the way it participates in a widely known myth, illustrating it. It’s a miniature in spirit, and not in letter, so to speak.

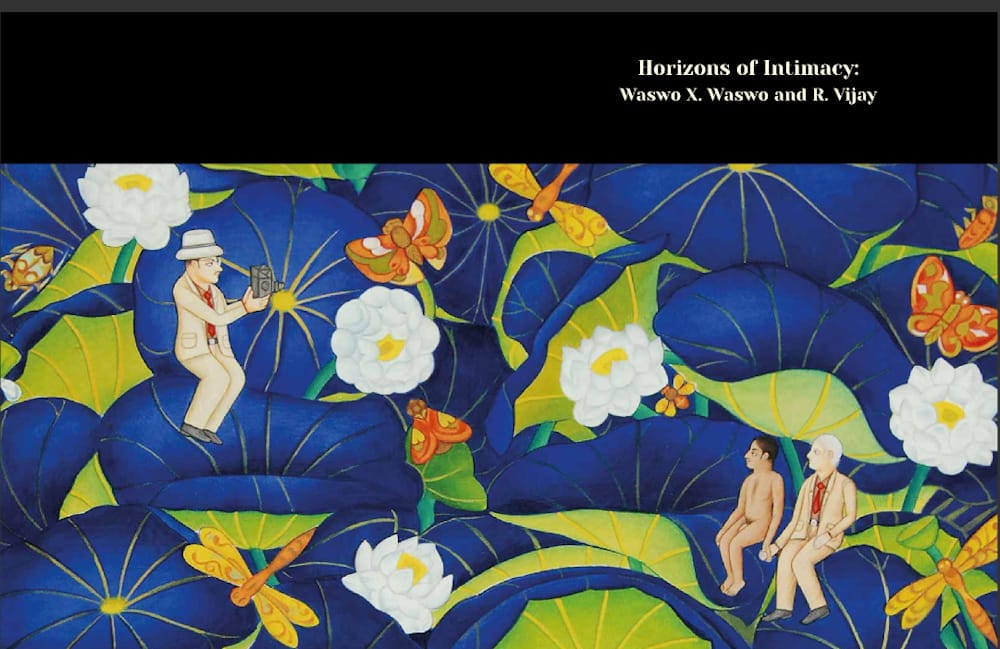

Waswo X Waswo and R Vijay work with an element of playfulness in their work. For the years they worked together, Waswo shared concepts for paintings and Vijay executed them, bringing them to life. Their work takes an existing framework of iconography or style to reflect upon it in the contemporary moment, and in the process, introduce self-reflexivity within a specific work. For instance, the large sized painting Lakshmi (1896) by Indian artist Raja Ravi Varma gets reworked as the miniature work I See Myself as Laxmi (2007) by the duo. The two are largely the same in terms of the setting and the background details except that the latter has Waswo standing as Lakshmi in the lotus. He is the patron/commissioner of the painting loaded with cash and is unapologetic about it. Most of the paintings by the duo have a sense of humour and contribute to the project of reinventing the tradition of Indian art.

The phenomenon of miniature works illustrating a text is interpreted differently by Nilima Sheikh who paints in terms of narratives. Her When Champa Grows Up (1984) is a series of 12 consecutive images and shows the story of the girl Champa as a common story of Indian women: they are children, they get married in their teens, they live suffocating lives with the in-laws, and they become victims of dowry deaths. This is a story familiar to those familiar with dowry deaths in India, especially in the 1980s. Sheikh turns to history and society as texts: she has worked on the violence prevalent during different periods in Indian history such as the Partition and the anti-Sikh riots of 1984.

There are many more examples in Sen’s book and it is a treat for art enthusiasts. Its approach towards curation and reflection ought to make Indian art more accessible to general readers by triggering questions such as: what is the frame of reference for Indian art and artists? What can art history do to connect contemporary work with the work of the anonymous masters? In which spaces do these connections work (and fail)? How do the artists turn to the myths and history for form and content? These are fascinating questions that can help one contextualize Indian art in general.

You must be logged in to post a comment.