This new collection with an unbeatably eye-catching title opens with the eponymous novella. “Courtesans Don’t Read Newspapers” takes more than a few (albeit short) chapters to get to the heart of the story: the red-light district in Kashi (also referred to as Varanasi or Banaras in the novella) is slated to be shut down to make way for new construction. This wasn’t the first time the city had tried to drive out women and girls.

History was repeating itself. Thirty years ago, the red-light area was located in Dalmandi at the centre of the city, a place no one would consider a slum. It was instead known for the lavish kothas of the tawaifs. These kothas were frequented by feudal landlords, monied men and officers of the time. Dalmandi was celebrated for its abundance of culture and graceful murjas. There were gramophone records of songs sung by the women in these brothels, and there was that one famous Baiji who had maintained secret relationships with men from multiple generations of the same family. Many film actresses and classical singers of the era came from the district, their coarse pasts silently fading into shiny presents.

Decades later, the district had lost its charm and had become rundown, catering to rickshaw pullers and factory workers. Corruption rules and the police cannot be trusted to protect the prostitutes or young girls who live in the area. And the prostitutes who work there worry that they’ll be living on the streets if they are evicted. The proposed demolition brings more attention to the area than it’s enjoyed in decades, partly thanks to a young journalist named Prakash. As he learns, everyone in the area has an opinion on the prostitutes, ranging from concern, disdain, and everything in between.

If the conditions of the red-light district seemed shabby, the Varanasi slums in the next story, “Lord Almighty, Grant Us Riots!”, seem even bleaker when six children drown in the river floods.

The stench was unbearable. Everyone had covered their faces with kaffiyahs or gamchas, except for the children. Behind the men stood the women, bursting into intermittent bouts of sobs and hiccups, their burkas and kurtas hitched up to their knees. Occasionally, a faint tremor of wailing rose from the group, only to be whisked away by the wind.

The title of the story comes from words painted on the side of a boat, “will come in riots”. This phrase appears later in the story when the slum residents are so desperate for change after all the death and destruction from the floods. Some muse that change is welcomed even if it’s something as tumultuous as a riot.

Not all stories are this bleak. In “The Magic of Certain Old Clothes”, Nalin and Neelima, have many of the luxuries a young couple could wish for: a house and car and the means to eat at nice restaurants whenever they want. To any outsider, they appear as the perfect couple. But one day they happen upon a second hand store of designer clothes. Neelima holds up a shirt and says she’ll buy it for Nalin as he looks on in horror. He can’t imagine wearing someone else’s clothes and this one trip to the second hand store causes a rift in their relationship, the likes of which they haven’t experienced before. The other three stories are just as engaging and full of complex characters and colorful settings.

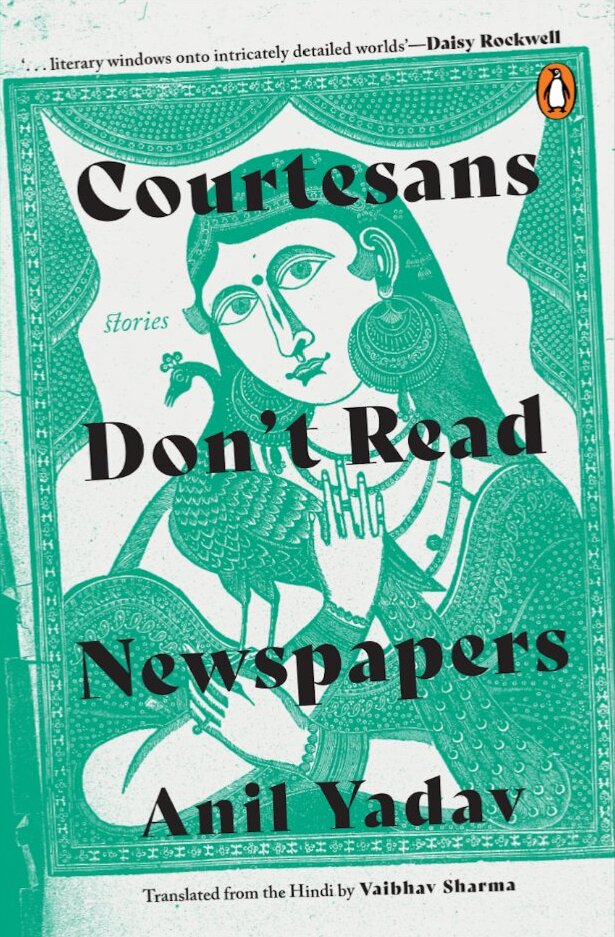

Anil Yadav combines humor with the somber realities of everyday life. Vaibhav Sharma translated this book as part of an application for a translation mentorship program. In his translator’s note, he writes that he was drawn to Yadav as a storyteller who listens to “voices that question the status quo.” If English-language readers end up reading stories about courtesans and newspapers, he’ll have been right.