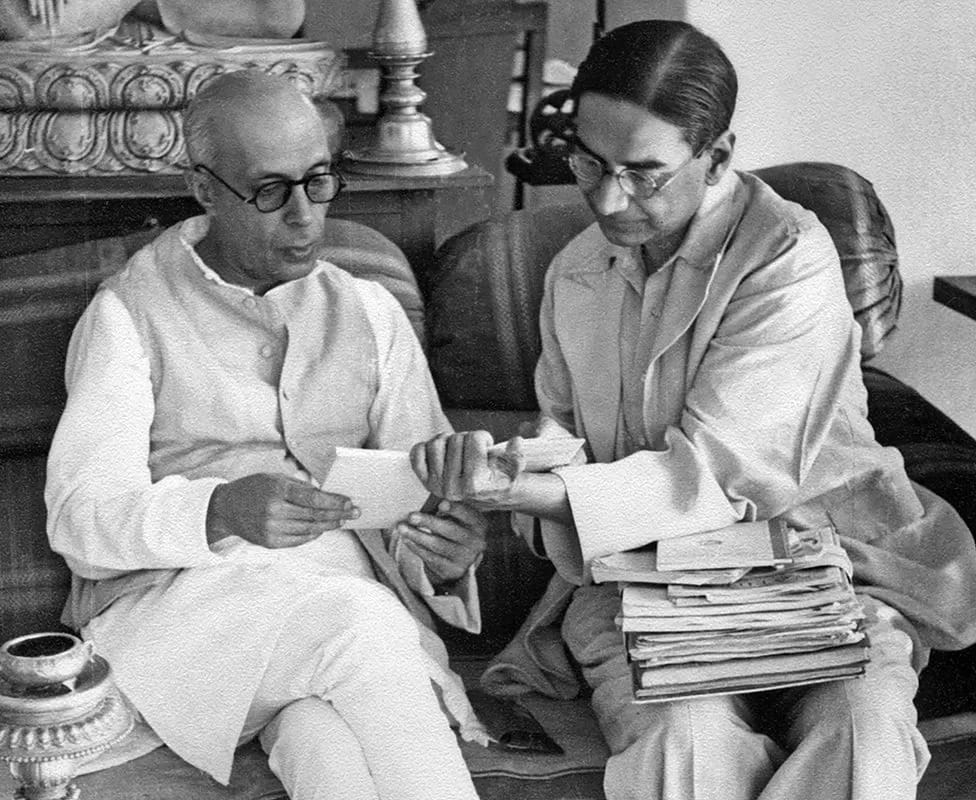

“Thou art the ruler of the minds of all people, dispenser of India’s destiny. Thy name rouses the hearts of the Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat and Maratha, of the Dravida, Orissa and Bengal.” Thus begins Rabindranath Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana. In 1939, Jawaharlal Nehru traveled to Calcutta and received Tagore’s blessing to make it India’s national anthem. That meeting took place in the home of Prasant Chandra Mahalanobis. Equal parts flawed, driven, and brilliant, Mahalanobis went on to steer the Five-Year Plans that promised to catapult India into modernity. Nikhil Menon’s new book Planning Democracy: Modern India’s Quest for Development captures this technocrat in full: how he amassed and exerted influence, and how reality fell short of his ambitions.

The book’s first section spans Mahalanobis’s career from his Cambridge graduation to his death in 1972. This charming, worldly, and cosmopolitan physicist turned statistician seemed to know every figure of the age, from Albert Einstein to Zhou Enlai. Calculating in both senses of the word, Mahalanobis founded the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) at just the moment politicians needed evidence to justify their industrial fantasies. Over decades the academic evolved into a bureaucrat, capable of usurping the authority of economists and elected officials alike. He understood that data could guide policy instead of simply tracking it. By eschewing broad measures of social progress like poverty rates in favor of narrow physical targets like steel output, Mahalanobis made the government reliant on the apparent precision of his input and output tables. Along the way, he leveraged his connections with the Soviet ambassador to make sure that ISI received the country’s first digital computers in the 1950s.

Menon situates Mahalanobis in an age of “quantitative positivism”, where economic theory and political practice both pushed a consensus in favor of economic planning, especially for nations emerging from colonial rule. Menon documents the occasional contrarian arguing from Gandhian, right-wing, or feminist perspectives. But in the face of prevailing sentiment, not least Nehru’s Fabian outlook, those voices received scant attention.

Mahalanobis’s technical and administrative acumen produced many genuine accomplishments. He founded the International Statistical Education Center, an institution that would train statisticians from across the developing world. He mentored a generation of economic and statistical talent, including the Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen. But his true legacy rests with the National Sample Survey. That exercise forever established the scientific validity of random sampling and represented enormous logistical achievement in its own right: the inaugural survey covered more than 1,800 villages in over a dozen languages.

Menon balances those achievements with a fair appraisal of Mahalanobis’s flaws. He mingled with top academics the world over, but never seemed to encounter anyone who counseled more reliance on market mechanisms. Unbeknownst to Mahalanobis, his frequent expressions of sympathy for the USSR likely prevented India’s acquisition of the American UNIVAC computer. He paid the female half of India’s vast workforce almost no heed, leaving the promotion of labor-intensive handicrafts to his wife while he focused on investment in capital-intensive factories. Those blind spots led Mahalanobis, and India, directly to the failure of the 2nd 5-year plan in 1956, when India’s strategy of import substitution created a foreign exchange crisis. Mahalanobis’s prestige never recovered, but the elite faith in planning remained. In 1963, a survey expressed the government’s disappointment to discover that most Indians still “lack an intelligent understanding of the essentials of planning.” But if the common man lacked understanding, he certainly did not lack awareness.

The book’s second half offers a detailed study of the state’s efforts to promote what amounted to a secular region. Both unable and unwilling to resort to force, the Congress Party had to veneer top-down planning by elites with democratic rhetoric and appeals to patriotism. The promotion of planning took myriad forms: the government sponsored plays, movies, exhibitions, and periodicals. One publicity stunt distributed 100,000 propaganda-emblazoned kites. Menon also includes a chapter on efforts to encourage “oxymoronic entities—government initiated voluntary organizations.” These efforts centered on distinct social groups like villagers, college students, and the wandering holy men known as sadhus. Much like the Plans, it all amounted to little.

Everyone from the editor of the high-brow journal Yojana (The Plan) to wandering troupes and Hindu mendicants happily accepted government funding. How many of them actually understood or promoted the tenets of economic planning was less clear, to say nothing of their audiences. The Service to India Society harnessed village-level labor in the construction of roads, wells, and embankments while conveniently providing a sinecure for the young Indira Gandhi. The influence of the sadhus proved less benign. Despite Nehru’s misgivings, several prominent Congress Party members enlisted the aid of these devout Hindus to support and promote their agenda. Predictably, Congress soon found itself aligned with Hindu nationalists with little interest in the party platform. From their headquarters in Delhi’s posh diplomatic district, the sadhus pushed a saffron-hued agenda that culminated in a 1966 riot on the very steps of Parliament.

Through it all, India’s leaders never confiscated savings or conscripted labor. They romanticized rural farmers but did not collectivize agriculture. Calls for a “new man” echoed Soviet rhetoric, but their methods stopped short. The states were too diverse, and civil society too strong, for the central government to impose itself without the consent of the governed. Without centralized power, central planning could not veer into totalitarianism, nor could it threaten the hold of patriarchy and caste across the subcontinent.

Through bureaucratic inertia, the Planning Commission survived until Prime Minister Narendra Modi abolished it in 2014. And while its death went unmourned, its accomplishments deserve Menon’s tribute. Planning offered a secular narrative to unite a vulnerable country across lines of class, caste, language, and religion. If India fell short of its ambitions, it also avoided the full-scale civil wars that racked Burma, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The Congress Party seized the commanding heights of the economy, but without letting go of their fundamental preference for democracy.

Bad policy stunted the economy for decades, but those same policies steered them away from the catastrophes of Communism. Democracy has enabled India to choose a different trajectory since 1991, a path that could afford it a leading role in the 21st century. It seems that the dispenser of India’s destiny may yet bring Tagore’s verses to life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.