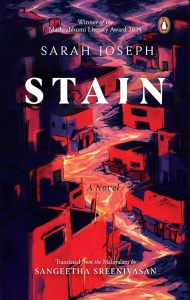

Author and activist Sarah Joseph was born and raised in present-day Kerala, known for both Jewish and Christian populations dating back well into the first millennium CE. A Christian herself, she writes both poetry and prose in Malayalam, often centering around religion and feminism. A decade ago she won accolades for a novel based on the Ramayana. Now she has a new novel, Stain, translated by Sangeetha Sreenivasan, that re-imagines the biblical story of Lot, largely set in the town of Sodom. Although readers of the English translation will undoubtedly be familiar with the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, one would have to assume that Joseph’s original Malayalam audience either also know the story or find resonance in a biblical story set long ago and far away.

Throughout the Judeo-Christian world and mostly likely beyond, Sodom will probably evoke images of fire and brimstone, violence and destruction. That doesn’t take place until later; when Joseph first introduces the town, it seems idyllic.

Among the houses clambering up the slope, small green isles of trees appeared here and there—fig trees spread wide, ancient olives, palms, almond trees, towering cedars with crowns high like flag posts, and the ever-green sacred berosh, the cypress trees. The town, glimpsed through this tapestry of greenery, revealed itself in the whiteness of limestone and the yellowness of sulphur stones. Beneath a vast, cloudless sky lay the Sea of Arabah, bluer than the sky itself, deeper in its own secret hues.

Despite being set in Biblical times, the story sometimes reads as if scenes could take place today. Joseph writes in her acknowledgments that she traveled to Jordan to research this book, and scenes from this trip are apparent in parts like this:

In the Jordan Valley, this was the season for drying figs and grapes, filling cellars with new barrels while removing the oldest. Olives were moved to hammer millstones, the sound of donkeys turning the crusher’s beam echoing for days. Workers’ voices mingled with the sounds as they packed olive paste into cloth sacks. Capping the sack mounds with a crushing stone to extract olive oil was a celebration in itself. Imagining the sparkling, golden olive oil, they felt surrounded by the scent of baking wheat bread—the sourdough kneaded in olive oil, cooking on the skillet as the hot desert wind blew relentlessly. They remembered the peaceful light and scent of lamps burning olive oil.

There are other parts that have become popular expressions, if not tropes, such as this this message Lot relates from his uncle Abram (the Biblical character later and perhaps better known as Abraham):

So hear me: if a hand is broken, let the breaker’s hand be broken. If an eye is blinded, blind the one who did it. An eye for an eye. A tooth for a tooth. Let justice stand on level ground.

Abram himself features in the story, not least when he provides a theological rationale for, if not quite monotheism, then one almighty power.

Abram ignited endless debates around a single question of power—who truly holds dominion over the lands, who sets the earth in motion? For the worshippers of the moon, it was the moon; for those devoted to the sun, it was the sun. Yet Abram challenged this, asking: Could the moon, fading at dawn, or the sun, vanishing by night, truly govern the earth’s course? Not, he argued, the true Lord must be the creator of all things, including the sun and moon. With authority, he declared, “Let there be” and all things came into being.

The historicity in the novel is sometimes a bit vague—perhaps understandably so given the original story is not firmly tied to chronology. Abram moves around the region with his wife Sarai (Sarah), including places like Aleppo and Damascus in today’s Syria, which were in fact settled during this broad period. Other regions such as China and India are also mentioned, probably anachronistically in an early Old Testament context. Lot travels around the region trying to help cure people of their ailments, including addiction to opium. In one area, he comes across some people who had received an elixir to cure them from addiction from two traveling healers, one from India and one from China. Not much later, Lot meets the two men at the Dead Sea, where they are collecting the legendary healing mud.

When Lot reaches poor areas, people are often suspicious because his home of Sodom is free from poverty and because he believes in one god, while they worship many. As most readers of the translated version likely already know, death and destruction go on to befall Lot and his family. Even after Lot’s wife Edith is turned to salt and his daughters become pregnant under unsavory circumstances, he tries to keep his faith.

You must be logged in to post a comment.