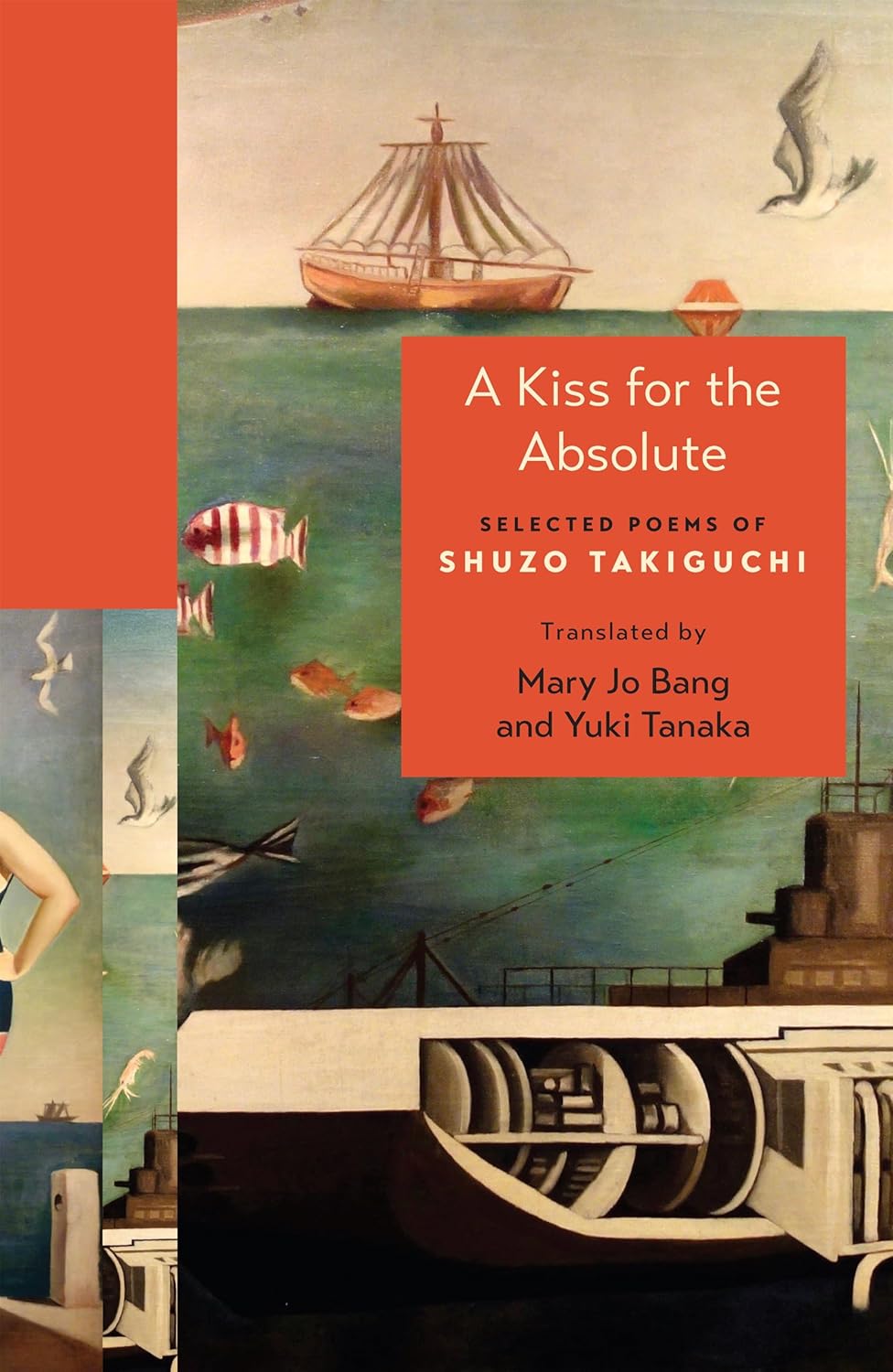

Who is Shuzo Takiguchi? Neglected and out of print for decades in Japan, ignored by the anglophone world, awareness of his contributions to 20th century Japanese writing and fine arts is long overdue. Profoundly influenced by French surrealism, Takiguchi’s heady mix of mythological rumination and avant-garde modernist poetry has finally been made available to an international audience with the bilingual publication of A Kiss for the Absolute: Selected Poems of Shuzo Takiguchi, translated by poets Mary Jo Bang and Yuki Tanaka. Meticulously harvested from a cache comprising a ten-year period of intense literary composition from 1927-1937, this edition of thirty-five poems gives needed shape to Takiguchi’s wide-ranging legacy as an eclectic visionary—critic, translator, poet, artist, collector, curator.

In a comprehensive introduction, Bang and Tanaka reveal the many precarious twists of fate that came to define the remarkable career of Shuzo Takiguchi (1903-1979), starting with the catastrophic horrors of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, an event that halted his studies at Tokyo’s Keio University for two years. Returning to the classroom, he became enamoured of surrealism through contact with a group of intellectuals associated with legendary poet and critic Junzaburō Nishiwaki. Quickly abandoning competing distractions, excited by surrealism’s valorizing of spontaneity and chance, as well as its emphasis on intuition and unconscious imagery, Takiguchi threw himself into poetic composition.

Dedicated to the surrealist cause, he became a respected long-distance correspondent of André Breton, the movement’s founder. Translating and reviewing European authors, Takiguchi was a dedicated conduit between surrealism’s Western practitioners and Japan. Despite this fruitful relationship, however, he was not an unquestioning follower of Breton’s famous manifestos. He preferred to remain true to his own taste, although devotion to modernism eventually got Takiguchi into trouble. Bang and Tanaka reveal that in March of 1941, Takiguchi was

arrested by the Tokubetsu Koto Ketsu… the Special Higher Police…and held for eight months…for being a ‘thought criminal,’ a category that included anyone influenced by the West.

Instructed on his release that he should guard his words and actions more vigilantly, Takiguchi quit poetry for painting. Writing only art criticism afterward, he went on to curate hundreds of exhibitions, tirelessly promoting surrealism in Japan until his death.

But Bang and Tanaka’s introduction provides more than biographical data. Pulling back the curtain, they offer an insightful glimpse into the intricacies of a translation process that took a decade to complete. Loyal to Takiguchi’s original intent, while still aiming for fluency in English, Bang and Tanaka aspired “to capture the distinctive way Takiguchi uses language in the poems,” including “cultural and literary allusions, as well as the history of his era, and the ways in which he encoded his preoccupations and obsessions.” Unresolvable questions of “equivalency in English” were dealt with by “[creating] wordplay elsewhere to maintain the same level of play as occurs in the original.” Utilizing the design format en face, Bang and Tanaka elegantly present each poem in Japanese on the page opposite every translation, allowing Takiguchi to be explored through the lens of either language.

Dreams stack on top of each other like a sheaf of film stills.

Without doubt, Takiguchi’s poems cut the eye. He wields the precise arrangement of his lines like a sharp blade: “gaiety winks in a shattered mirror” (from “Snapshotting”); “A labyrinth made of air” (“Fairy’s Distance”). Memorable frozen moments accumulate from disparate images: “Kick-scattered stars,” “Water has a heart, birds have clarity,” and “A pyramid of a thousand rainbows” (“The Sphinx in May”); “I button up the stars of my shirt,” “the rain’s fingers look like the mitts of mice” and “a public park of the retina” (“The Rock Cracked Up”); “A dream stowed away in a pebble” (“Drowsiness”).

Dreams stack on top of each other like a sheaf of film stills: “Inside the express train, I’m a field of gemstones” and “I am an infinitely tall sailor disguised as the rose inside the powder room of a ship on heavenly lake water mirrored on the surface of an inland lake” (“MIROIR DE MIROIR: MIRRORED MIRROR,” one of five poem titles printed in all caps). Takiguchi overwhelms with layers of glittering imagery, expressing more in a mere four lines than most scholars of art could in a trove of critical studies:

The sorrowful eyes

of soaring birds

get hammered into our blood

like songs

(“Pablo Picasso”).

Takiguchi’s constructions are enigmatic devices evoking the paradoxical ambiguities at the ethereal center of human identity. Built from the glimmering elements of his own personalized library of phantasmagoria—ships, mirrors, wind, sky, rainbows, eyes, stars—he generates fresh connotations with each reprise and restatement in successive poems, perpetually encouraging inward reflection akin to Zen koans, like in “Étamines Narratives”:

The farmhand who willingly removes his cap in front of a blinding imbalance will never accept any categorical imperative unless it comes from a mole spilling its chlorophyll… Two windpipes can’t stand up to poetry.

Extracting mythological elements from traditionally classical contexts and contrasting them alongside de-familiarized everyday objects, he experiments with startling coincidences and surprising connections, steering perception away from stale routine:

The angel joining the Koi star cluster took a peek at the mirror of a plum blossom’s pistil and discovered me for the very first time…I am a dangerous virgin

(“DOCUMENT D’OISEAUX: DOCUMENTING BIRDS”)

and

A bed of light born inside a slipped-off sable stole. Her swoon assumes

an eternal oval. The beautiful game where one mistakes water for land

will soon come to an end.

(“A Kiss for the Absolute”).

Allusions from ancient and contemporary mythology and global culture imbue these verses with stylish cosmopolitan sparkle. Some but not all of them include: Gertrude Stein, the Virgin Mary, Tristan Tzara, Scheherazade, Aragon, Botticelli’s Venus, Éluard, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Mars, Leda, and the Greek god of music, prophecy, and the sun, an occasional stand-in for Takiguchi himself: “Every shore is omnipotent and the trunk of a Greek tree again conceives of an Apollo” (“DOCUMENT D’OISEAUX: DOCUMENTING BIRDS”).

Troubling and transforming, Takiguchi’s word-mirrors are mystic portals into an estranging but shared otherness.

Just as intrigued with mirrors as he is with erudite references, Taliguchi embeds in his poems a preternatural looking-glass in which new notions of subjectivity, gender, and spirituality are silvered:

In the mirror where the wheat field is drying, the skeleton of a whale

rises like the morning sun … Zero’s peacock will sip water from a yellow

mirror, and the millionaire’s waterfall will shroud the white canvas sail

on the owl’s head. It’s the rebirth of white pelicans in the timelessness

of infinite time and, oddly, breasts: the milk of the enormous forest that

wet-nursed copper and owls. Black cloud milk, star milk…

In the morning, I breastfeed the lady-doves who gave birth to my seven mirrors.

(“MIROIR DE MIROIR: MIRRORED MIRROR”).

Troubling and transforming, Takiguchi’s word-mirrors are mystic portals into an estranging but shared otherness: “I who am pregnant go into the sea with lightheartedness and a bright candle” (“DOCUMENT D’OISEAUX: DOCUMENTING BIRDS); “I sympathize with the starfish;” “I, a ship that weighed anchor, see charcoal with its frizzy hair” (“The Sphinx in May”); and “It is I, a young girl, who demands a rationale for those enduring fountains” (“The Misdeeds of Cleopatra’s Daughter”).

His methodology upends the normal relation of things. Rather than writing on a mirror, it seems as if he insists on the reverse, adopting a mirror for his stylus. In this sense, Bang and Tanaka’s bilingual edition harmonizes nicely with Takiguchi’s liquid mercury style. Including the poems in Japanese alongside their English counterparts conjures the effect of two mirrors gazing, then merging into each other. “MIROIR DE MIROIR: MIRRORED MIRROR” is, in fact, an eerie precursor, anticipating Bang and Tanaka’s en face format as mutually reflecting “mirrored mirrors,” replicating Takiguchi’s clever mirroring of European surrealism back to itself.

Eyes feature here along with mirrors.

Eyes feature here along with mirrors. Takiguchi’s eyes ingather a universe structured like a poem: “Like the eye everything is glistening / Like the eye everything is invisible” (“Reactions”) and “an infinity staircase inside an enormous eye” (“Man Ray”). Once surrendered to Takiguchi’s rhetorical undertow, he leads us beyond his ingenious surrealist centrifuge, and into wisdom:

His faint mustache speaks of a natural disaster in the Country of Wax. She is moving back and forth, coming and going, in a lipstick lens that is burning up time. The secret of personal pronouns. The secret of time.

(“A Kiss for the Absolute”).

A Kiss for the Absolute includes both long metaphysical works and short sensual odes, showcasing an array of diverse skills and capabilities, different facets and dimensions that infuse his poems with a revitalizing polyvocal energy. In particular, Takiguchi’s suite “Seven Poems” (a possible mirroring callback of the “seven mirrors” above) is a set of quicksilver tributes, deeply moving, rich in music. Named after Picasso, Dalí, Max Ernst, Magritte, Miró, and Tanguy (“Everyone / waits for everyone else / on an unknown / and yet familiar / never ending chessboard”), Man Ray inspires Takiguchi’s most voluptuously plangent verses:

Shadow-lovers live inside the body

Listen to whispers

on an infinite staircase inside an enormous eye

Lovely words

transform into birds of light

inside gigantic crystal oculi

Panthers all out of lovely light are standing on their hands…

Light’s naked body

Warm blooded could run

faintly through a statue.

(“Man Ray”).

Takiguchi is uninhibited in celebrating life’s epicurean pleasures: “Delicate life at the bottom of a bottle / I drink you up” (“The Echo’s Rose”); and “The freedoms and hollows of unabashed beauty / You are a radiant plum” (“The Sphinx in May”). On the other hand, he understands that unfulfilled desire brings suffering. With a yearning heart, Takiguchi can summon an epic sense of erotic loneliness:

In the fossilized water that brightens day-by-day

my desire still swims…I, bastard child of a huge chandelier called the blue sky

No one refers to me as the subtle sphinx of love

(“The Sphinx in May”).

In Japanese, the term for “poetry” comprises two characters: “word” and “temple”.

While his lush shorter lyrics are sexy, moody, and reflective, Takiguchi’s longer poems stretch to grasp the transcendent. Expansiveness gives Takiguchi the opportunity to exercise different technical chops and slowly accelerate toward the sublime, like in title poem “A Kiss for the Absolute,” where the sculpture “Venus de Milo” incarnates the clout of the universal feminine:

Nothing of her arm’s midsection exists. For just one moment, she’s like some eroded Goddess of Beauty. She’s the heat in the hot wind or the iron in an iron. Even so, her song is the bird in the ashes…Her torso is a wilderness of difference, a flaming missive in which a mercury headstone becomes gravid, it’s the broad daylight’s spirit level … Her tempest. Her legend.

In Japanese—as Bang and Tanka parse in their introduction—the term for “poetry” comprises two characters: “word” and “temple”. Mary Jo Bang and Yuki Tanaka deserve massive plaudits for assembling this worthy word temple, and entitling it A Kiss for the Absolute is more than apropos. Takiguchi’s oeuvre strives to attain an erotic connection with the ineffable. He endeavors to use his poems as a “kiss” to touch the elusive divine force animating his heart and pen, always seeking to become one in a mystical embrace with that anonymous and obscure “absolute” deity that innervates the universe. Lines from “Stars on Earth” invoke this libidinal dimension of ache and act. Poetry is a sexual and spiritual shrine:

I write a verse as old as a Tibetan temple

Then tear it to pieces

I write a verse

I write the word temple

Then tear it to pieces

It smelled of red roses

It smelled of gasoline.

Her cheek seen fogged like ice

Her sex seen misted like flowers

And birds will go on forever

living in the wind

like erratic rocks.

“A Kiss for the Absolute” concludes with an ellipse, three dots suggesting life is an unending road to a sacred place of worship. Enter Shuzo Takiguchi’s temple of poetry and remain dazzled forever: