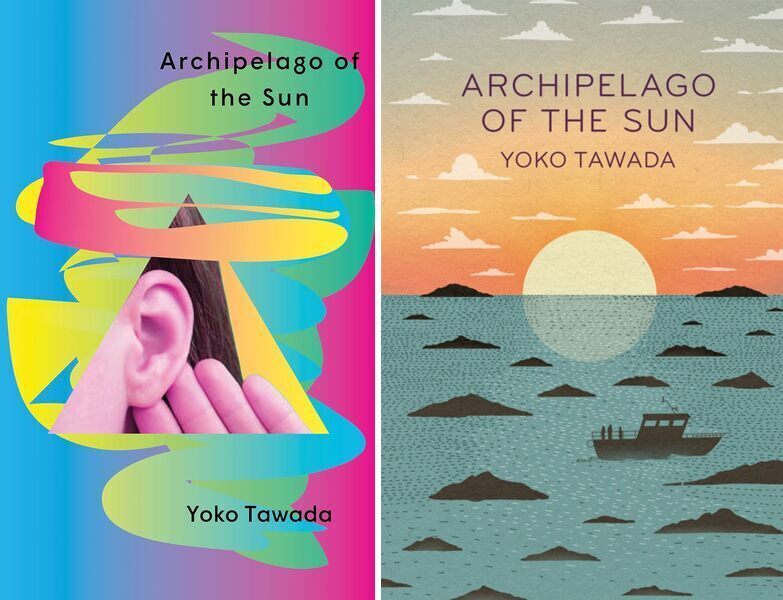

Yoko Tawada’s Archipelago of the Sun, translated by Margaret Mitsutani, is the third and final instalment of a trilogy. The first two volumes—Scattered All Over the Earth and Suggested in the Stars—introduce a diverse cast of characters centered around Hiruko, a Japanese woman in search of her homeland, which seems to have vanished from the earth and almost from memory. Along the way she befriends a Danish linguist, a transgender Indian, a German museum worker, an Eskimo sushi chef, and a seemingly ageless Japanese cook. This motley group accompanies Hiruko in her search, which takes place across a near-future European landscape in which contemporary ecological and political issues have intensified. Europe is a tranquil welfare state while America has become the world’s largest manufacturing base. The climate has been horrendously damaged, causing the collapse of many ecosystems and the cultures they support. Immigration has become a necessity for many, even while some borders have calcified, and geopolitical tensions abound. And, of course, there is the looming question of what happened to Japan. (Did it sink beneath the sea? Enter political isolation? Or was it simply forgotten?)

Archipelago of the Sun finds Hiruko and friends on a mailboat sailing east on the Baltic in the hope of somehow eventually reaching Japan. As with the previous installments, the book is narrated by each character in turn, with many stylistic changes to indicate shifts between languages and especially Hiruko’s homemade language of “Panska”—transitions that are expertly translated by Mitsutani. Also in keeping with previous installments, Archipelago of the Sun has little by way of action, instead unfolding over the course of many conversations between characters. What little happens in the book is largely incidental to the ideas being discussed, with elements of surrealism and even mythology further contributing to these wider meditations.

Through long, profoundly multilingual conversations, Tawada asks questions about history, identity, politics, and especially language.

Through these long, profoundly multilingual conversations, Tawada asks questions about history, identity, politics, and especially language. The common denominator here is fluidity and change. Just as Hiruko searches for her past—for the foundation of her identity—in the form of a homeland that may no longer exist, a stable core for cultural, political, linguistic, and gender identity proves elusive. The borders the characters cross are ephemeral, the differences between languages are porous, and the environment itself has changed radically.

Tawada does not suggest, however, that all such identity—whether personal or cultural—is illusory. Rather, her meditations point toward a dialectic where identity is primarily relational, always having to navigate ever-changing context and history. “We were like those waves,” Hiruko states.

We pushed against each other, bumped into each other, lost our shapes and found new ones, and gently rocked as we faced in different directions.

This wider context both allows and restricts expression. Political borders may be ephemeral, but they are still rigidly guarded. Languages may be porous, but Hiruko at times struggles to express herself depending on which language she is speaking. Some portions of identity clash with others; some elements of one’s past fail to find expression in the linguistic modes of the present.

The conclusion to which Tawada leads the book suggests a way through such effervescence and contradiction: to embrace it. Hiroku strives to allow all these various relationships, however fractious, to coexist inside of her: “I want to be a house that everyone can live in,” she says. Doing so allows the search for the homeland to continue, for identity is established in embracing the whole range of fluid, contextual relationships. In this sense, then, the search for the homeland is the homeland:

If a journey goes on long enough, traveling itself becomes the destination. And when that happens you don’t need to be in a hurry anymore, so anything goes, and you start to enjoy having your past mixed with the present. The past stops being something you have to cut off, throw away.

Only in this way can the book’s characters truly travel together.

Archipelago of the Sun floats between worlds, between identities, histories, languages, and cultures.

Archipelago of the Sun represents a tranquil and satisfying conclusion to Tawada’s trilogy. It is a strange, meandering book. It never ceases to defy expectations and to consider profound questions from unusual angles, and frequently from many perspectives at once. It is almost a philosophical novel, but one that overflows with character, beauty, and wit. Its dialogue probes vast spaces, though it can at times become somewhat dry, and the way in which the characters speak can feel stiff, almost inhuman.

Fortunately, this mostly serves to contribute to the novel’s uncanniness. Tawada presents many questions and innumerable puzzles, many of which appear as points of departure; they are opportunities for travel and discussion rather than problems with definitive conclusions. Through its ceaseless exploration, Archipelago of the Sun floats between worlds, between identities, histories, languages, and cultures. It is a joy to travel with it.