“Untranslatable”, concluded the erudite, 17th-century Jesuit missionaries, referring to the glorious corpus of Chinese poetry. While they acknowledged that poetry played an outsized role in Chinese civilization, they limited their translations to histories and scientific texts. They knew of but didn’t try to tackle the Book of Songs or the Tang dynasty anthologies. We can explain their reluctance by recalling that in their era, Latin and Italian poetic forms shaped their tastes just as strictly as ancient Chinese forms limited that of their hosts. They could not translate Chinese poetry into Petrarchan sonnets or Horacian odes, so they didn’t.

Two centuries later, Europe had changed. The formalism of preceding centuries, and the sentimentalism of the Romantic movement, left poets and readers searching for something new: pure beauty. France’s Parnassian school celebrated art for art’s sake. The school’s high priest was Théophile Gautier (1811-1872). A bon vivant and free-thinker, his idea of educating his daughter Judith (1845-1917) was to give her the run of his extensive library. She never looked back.

Surprisingly, the book was a runaway commercial success.

19th-century Paris has been called the Capital of Europe. With their claim to the universality of the human experience, French men and women of letters explored all civilizations, ancient and modern. Yet as Pauline Yu shows, their access to Chinese civilization was surprisingly limited, and they felt that “the history of literature would be incomplete if it neglected the Chinese poets,” as one writer lamented. The treasures plundered by French troops from the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) in 1862 in the Second Opium War constituted a major source of information about China. A Shaanxi scholar named Ding Dunlin constituted another. Ding arrived in France under mysterious circumstances, without means to support himself. Théophile Gautier magnanimously invited the exotic foreigner to live with his family in 1863, despite much casual racism in his wider circle. Ding’s story in mid-19th century France mirrors that of recent immigrants in Paris, with little humiliations and tales of persistence. Ding tutored Judith, an eager student of Chinese. From this partnership arose an outstanding work of French literature, the Book of Jade (Livre du jade) in 1867.

Judith Gautier’s book responded to a deep need of the Parnassus generation. They sought beauty without sentiment, music without formalism. Judith found inspiration in Chinese poems to write precisely in this way. Pauline Yu provides us with a deep reading of both the Frenchwoman’s poems, as well as her Chinese models, including Du Fu and Li Bo. She approached her translations with great sensitivity. Sometimes she followed the sparseness of the Chinese; in other cases she elaborated on the images or supplemented the allusive Chinese with more context. As a result, some of her poems represent translations, others, inspirations. Yu writes, “The house in the heart proved to be one of [the so-called] Du Fu’s most famous poems.” Judith largely invented this poem, and yet, continues Yu “It would be retranslated more frequently than any other poem in The Book of Jade, at least six times into English alone, and it was selected as one of the hundred most beautiful poems in the world in 1979, although erroneously attributed to another French poet, Louis Laloy.”

Surprisingly, the book was a runaway commercial success, despite its costly production, and quickly went into additional editions. The fact of having been written by a woman caused much comment, most of it favorable. “Women are now capable of anything,” critics concluded. The lack of sentimentality and sweetness, so often associated with woman poets, struck the readers especially. France’s greatest poets, including Victor Hugo and Stephane Mallarmé, hailed her achievement. It is not hard to see the Chinese inspiration, with the focus on images and the absence of rhetoric, influencing Mallarmé, and after him, Paul Verlaine, and then all the European symbolist poets.

Despite Judith making no claims to being a scholar, or perhaps because, few Sinologists found fault with the book. They saluted its faithfulness to Chinese aesthetics, and how it presented the poetic world of the Chinese with its themes of flute music, moonlight, loneliness, water and wine. Her few mistakes occupied some paragraphs in specialist journals, but no one seriously challenged her. This was in distinct contrast to the venom and rivalry that characterized the beginning of Chinese sinology, described by Yu earlier in the book.

Yu makes a good case that Pound borrowed directly from Book of Jade.

Like the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Judith’s translation became the object of translation into other European languages, including English, Polish and German. The German translation, by Hans Bethge, proved to be, in its turn, a runaway best-seller. Gustav Mahler used it as the text to his great song symphony, “Das Lied von der Erde”.

For English readers the most famous, or infamous, translator from Chinese is Ezra Pound. This American had his own theory of Chinese poetry, based on the idea that every character was a visual idea, and that a Chinese poem is like cloisonné jewelry. Wrong-headed as he was, his hunch gave rise to a brilliant collection of poetry, Cathay, published in 1915. Did Pound escape Judith Gautier’s influence?

Yu makes a good case that Pound borrowed directly from her Book of Jade. But even if he did not, Pound is certainly an heir to the Parnassians, and was imbued with the aesthetic judgements that helped shape Judith and which she in turn shaped.

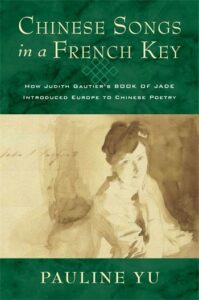

Yu’s engaging book is many things: a biography of one of France’s most original literary characters, a survey of the brilliant intellectual and artistic society of France’s 2nd Empire and 3rd Republic—with more than cameo appearances by Richard Wagner and John Singer Sargeant, a history of European sinology, a succinct but complete survey of Chinese poetics, a deep reading of many of the poems from Book of Jade, and finally an analysis of its remarkable legacy. Unsurprisingly, we learn from Yu that this book has been 50 years in the making. Readers trying to understand the cultural impact of China on the West will learn much in this erudite and exhaustive narrative.

You must be logged in to post a comment.