Anyone who has enjoyed learning a second language knows how productive the exchange between a first and second language can be. Yoko Tawada has published fiction and nonfiction in Japanese and German and demonstrates this principle more than most, having moved to Germany as an adult in 1982. She positions herself not as an immigrant author, but as “exophonic”, referring more generally to “existing outside of one’s mother tongue.”

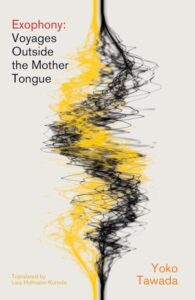

The way Tawada tells her own story in Exophony, this self-description alone has clearly irritated and confused a great many interviewers. Tawada’s first essay collection to be translated into English, Exophony: Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue, addresses many such questions posed to her, around the world, because of her choice not to write exclusively in her first language.

Tawada recalls being asked whether she writes as a German or a Japanese person. “This question always perplexes me,” she writes.

Tawada goes beyond merely “existing” in multiple languages, but rather has great joy in exploring, testing, and experimenting, then going back to her mother tongue, Japanese, to continue the process. According to Tawada, the procedure is universal to all multilingual people, but challenges monolingual audiences and publishers who want authors to fit in neater categories. She recalls being asked whether she writes as a German or a Japanese person. “This question always perplexes me,” she writes. She explains

The terms ‘immigrant literature’ and ‘foreign literature’ conjure images of an outsider coming in and taking up the domestic language in order to write something. ‘Exophonic literature’, on the other hand, implies that a writer is going from the inside out. How do I step outside of the mother tongue to which I am bound? What might happen if I did? [….] Sometimes a writer is made to write in a language that is not their own due to colonization or exile. And yet, if the literature produced by such circumstances is beautiful and interesting, I see no need to place it in a separate category from other kinds of exophonic writing.

Tawada is also aware that including authors who involuntarily write outside their native languages may erase racism or colonisation. Recalling a panel discussion in Korea, she writes

I realized how it sounded for me, a Japanese person, to be harping on about the joys of venturing outside one’s mother tongue–particularly here in Korea, where Japan had forced the Korean people into an exophonic condition against their will. People have no right to proselytize about the joys of exophony if they have never been forced to speak in a language against their will.

This, of course, is in an essay collection exactly about the joys of writing in other languages by choice.

At the same time, Tawada firmly and emphatically rejects the idea that a language is attached to a national (or nationalistic) identity, a common and problematic political claim both in Germany and Japan. Very subtly describing her own experience with racism in Germany, she writes, “I sometimes meet people who think they have absolute ownership over the German language simply because they are native speakers.” Tawada works through this discrepancy between her own largely positive experience with exophony and the knowledge of the negative sides of involuntary exophony to come to the poetic conclusion: “What I am really searching for is a language that has been freed of meaning altogether.”

Tawada is at play, but much more explicitly than in her fiction.

Exophony consists of thirty essays and is divided into two sections. The first section, “Voyages Outside the Mother Tongue”, addresses questions of exophony. Each short, self-contained essay begins with an exchange or interaction Tawada has had in various cities around the world. The essays are conversational, anecdotal and observational. Tawada lives exophony rather than propounding it; her arguments are based on her own experience and that of her interlocutors. Her explorations of exophony are slow, patient and generous.

The second, much shorter, section is “Adventures in German”. Here,Tawada is at play, but much more explicitly than in her fictional work. She free-associates with German words, grammar and idioms, moves into Japanese and back into German. For example, “Pulling Stories”, an exploration of the words semantically related to the German verb ziehen (to pull), begins: “Drawing a line from one point to another can be a fun activity”.

Connect-the-dots is a fitting visual metaphor for how Tawada plays in German. She begins with Charakterzüge (characteristics), invents the equivalent in Japanese (seikakusen, character lines), moves back to German to visit Gesichtszüge (facial features), before moving onto Zug (train), Badeanzug (swimsuit), Tee ziehen lassen (letting tea steep) or Kontoauszug (getting a bank statement). Each exploration of German is followed with an explanation of the equivalent in Japanese. While the second section is specifically about this kind of play, the entire essay collection is full of serious fun, despite Tawada’s concerns about being considered a mere punster.

Tawada considers the problems of exophony subtly and slowly. A hurried or inattentive reader will miss the point.

Exophony was first published in Japanese in 2003 and translated into English in 2025. The twenty-two-year gap is noticeable at times. For example, Tawada refers in passing to the Austrian right-wing extremist Jörg Haider, who died in 2008, or to German economic problems of the early 2000s. Tawada has not added a new introduction or made any changes to the 2003 edition, so the reader is left wondering if and how her opinions have changed in the last twenty-two years.

Just as in her fiction, she also refers quite casually to various prominent authors and thinkers. Some readers may wish for explanatory footnotes, but it is possible to go along with Tawada as she plays with language without knowing all of the cultural context. The Japanese edition featured Tawada’s own translation of German words, which the English translator, Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, has had to translate onward into English despite presumably not being a German speaker herself. Unsurprisingly, a number of mistranslations and misspellings have thus found their way into the English edition—although some of these errors may be from Tawada herself. Tawada ironically anticipates this:

We cannot travel without carrying the baggage of mistranslation. However, a ‘mistranslation’ and a ‘correct translation’ are not opposites, like a lie and a truth, but are rather both ‘translatings,’ journeys—simply different shades of gray.

German spelling errors are not the only challenge. English readers will find themselves confronted with a text set in the European literary scene twenty years ago, infused with German and Japanese wordplay.

Tawada considers the problems of exophony subtly and slowly. A hurried or inattentive reader will miss the point. Hofmann-Kuroda’s excellent translator’s note summarizes Tawada’s wandering argumentation and provides much-needed information about Japanese writing systems. It is thus better read as an introduction rather than as a postscript.

Not unlike readers of Tawada’s Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel (translated from German, rather than Japanese, by Susan Bernofsky), some English readers here may be overwhelmed by her quiet use of an otherwise unexplained German context. However, the initial Japanese audience had just as little knowledge of German as the average English reader, and Tawada’s use of German is, by her own admission, unusual. Disorientation is the point. In this way, even monolingual readers will be able to feel exophony, even if they don’t get all the jokes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.