I spend nearly half the year in Indonesia, so the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival always feels like a homecoming, the one place I can sit with local authors, journalists and historians, swap ideas about books and the country’s latest turns, and catch up with friends I only see once a year.

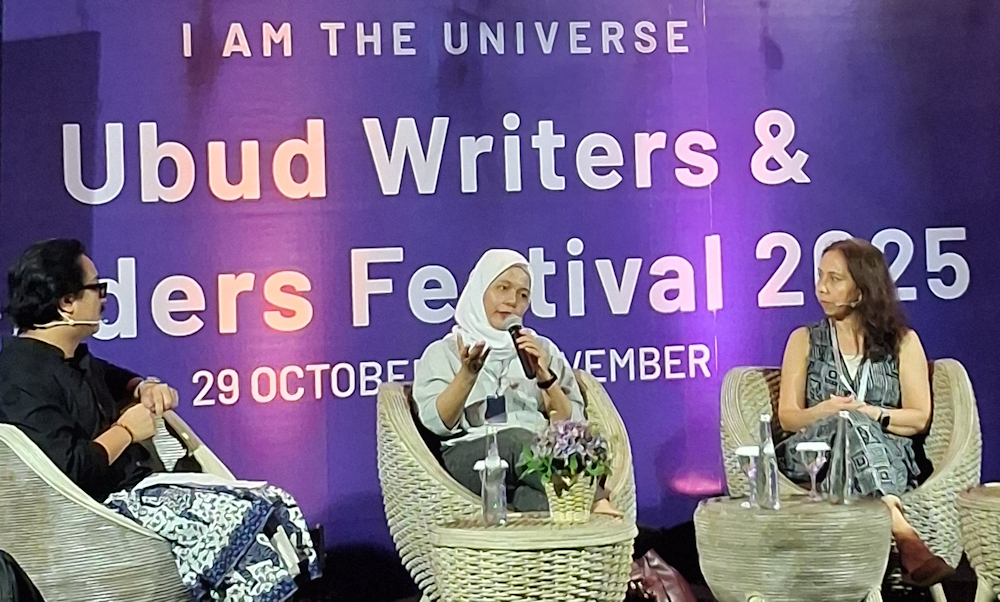

As one might expect, Indonesian authors anchored the festival. In their panels, private memories merged with collective wounds, giving rise to some memorable conversations. Ratih Kumala, an Indonesian novelist and screenwriter born in Jakarta in 1980, co-curated the Emerging Writers Program. She joined a session launching a bilingual anthology of short fiction, one of thirty-four free book events. Selected from 647 entries, ten new voices shared the stage with her and Nora Nazerene Abu Bakar of Penguin Random House Southeast Asia. The stories ranged from online feuds sparked by viral videos to disputes over village land. Kumala had judged the submissions alongside Shinta Febriany, a Sulawesi-born theatre director, poet, and playwright who founded Kala Teater in 2006 and leads the decade-long City in Theatre Project, and Ni Made Purnama Sari, a Balinese poet and novelist, whose debut Bali-Borneo (2014) won the National Poetry Day Award. Kumala’s own path began with Tabula Rasa (2004), a Jakarta Arts Council prize winner about a woman reclaiming her past amid city chaos. Gadis Kretek (2012, translated as Cigarette Girl) traced three generations through Indonesia’s clove-cigarette world; it became a 2023 Netflix series she helped script. Her 2025 novel Koloni, winner of Thailand’s Chommanard Women’s Literary Award, examines how colonial patterns persist in contemporary workplaces and households.

Leila S Chudori, an Indonesian journalist and novelist born in Jakarta in 1962, joined a panel on poetry’s evolution in the digital age with Sasti Gotama, Ray Shabir, Hamzah Muhammad, and Ni Made Purnama Sari. They debated verse thriving on Instagram as much as in print. Chudori introduced Namaku Alam, sequel to Pulang (2012), which followed an exile’s return after the 1965 massacres that killed up to a million suspected communists. Translated widely, Pulang earned the Khatulistiwa Literary Award. Laut Bercerita (2017, The Sea Speaks His Name) captured a student activist lost in Suharto’s final years. In 2023, she co-founded Peron House Publishing with her daughter Rain Chudori and edits the arts journal Porter.

Agustinus Wibowo, an Indonesian travel writer and photographer born in Lumajang in 1981, took the stage for a session titled Us and Them, drawing from his latest book Kita dan Mereka (2025). The work builds on his lifelong reckoning with identity as a Chinese-Indonesian who grew up amid the anti-communist purges and the 1998 riots that targeted ethnic Chinese communities. Rather than a memoir, Kita dan Mereka is a wide-ranging inquiry into the roots of human division. Wibowo spent years traveling conflict zones—Mongolia, Tibet, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and beyond—consulting over 350 books on history, anthropology, and geopolitics to trace how borders, faith, ideology, and race harden into fault lines. He frames the book as a mirror: every “us versus them” he witnessed abroad echoed the quiet prejudices he faced at home. After living three years in post-2001 Afghanistan, he published Selimut Debu (2007), a vivid portrait of Kabul’s grit and quiet grace. Garis Batas (2011) traces borders from Tajikistan to Java, showing how arbitrary lines on maps fracture ordinary lives.

Non-Indonesian writers brought fresh angles.

Banu Mushtaq presented Heart Lamp, her 2025 Booker Prize-winning collection translated by Deepa Bhasthi, who sat beside her. The stories tracked Muslim women and girls in southern India, their quiet negotiations with patriarchal norms, caste pressures, and religious expectations in everyday family life.

Other non-Indonesian writers brought fresh angles. David Van Reybrouck, the Belgian historian, archaeologist, spoke in the keynote about Revolusi, his 2020 history of Indonesia’s independence fight from 1945 to 1968. The book rests on hundreds of interviews with the last survivors: street fighters in Surabaya, clerks who typed Sukarno’s speeches, women who carried rice to guerrillas. Van Reybrouck subtitled it Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World. He showed how the archipelago’s refusal to return to Dutch rule sped up the end of empires from Algeria to Vietnam. Indonesia is marking eighty years of independence in 2025, so Revolusi ran through the program.

Patrick Winn, an American investigative journalist based in Bangkok,spoke on his second book, Narcotopia later in the week. The book maps the United Wa State Army in Myanmar’s hills, a militia that funded schools and roads with opium and methamphetamine. The session was moderated by Omar Musa, the Borneon-Australian author of Fierceland, which was launched during a separate event at the festival.

Pico Iyer, the British-Indian essayist and novelist born in Oxford in 1957, gave a talk on travel and silence that held everyone rapt. I spoke with him before the panel discussion. He told me he lives like a hermit with his wife in a small house outside Kyoto, Japan. They have no television or internet at home. He limits himself to one hour of email a day on a library computer. That way of life took shape after a 1990 wildfire destroyed his family’s Santa Barbara home while he was staying there. Flames five stories high swallowed everything, his manuscripts, possessions, even nearly his life as he fled with just his mother’s cat and a draft in hand. The loss stripped him bare, pushing him toward the solitude he craves. His new book Aflame came from years spent in a Benedictine monastery near Big Sur. He spoke about his love of Leonard Cohen, the singer-songwriter who became a Zen monk on Mount Baldy in California for five years, shaving his head and tending the garden while grappling with fame and inner silence. Iyer saw in Cohen a mirror for the writer’s calling: give up the world’s clamour to hear the quiet pulse of the heart.

The theme was Aham Brahmasmi, Sanskrit for “I Am the Universe”.

The festival was started by Janet DeNeefe in 2004, a few years after the Bali bombings which collapsed the tourism industry overnight. DeNeefe, a Melbourne-born expat who had settled in Ubud in 1984 after marrying her Balinese husband Ketut Suardana, responded by launching the event in 2004 to counter extremism and heal divisions and trauma with the power of literature, drawing visitors back through open conversation and shared stories. Twenty-two years later, that purpose still held. The theme this time was Aham Brahmasmi, Sanskrit for “I Am the Universe”, and the phrase showed up on signs and the program cover. Crowds arrived early each day. Balinese families settled into the front rows wearing light sarongs. Students from Java and Sumatra opened fresh notebooks. Long-term foreign residents stood in line beside tourists staying only a few days. The rooms stayed full and attentive.

On the final afternoon, rain swept in, drumming on tin roofs and herding everyone under awnings with coffee in hand, yet the conversations never paused. The festival stayed close to the ground: paths between stages cut through rice fields and roadside warungs steaming with mie goreng. Aham Brahmasmi was an appropriate theme: every voice added to the same picture. I left with the anthology in my bag and a reading list to carry me through the months ahead.