Prose poetry can be hard to get a handle on. It is literally oxymoronic, like “documentary fiction”; such terms are perhaps a recognition that most categories are really endpoints on a spectrum. As one now does in these situations, one asks AI, which unhelpfully replied: “Prose poetry is a hybrid literary form that adopts the structural format of prose—paragraphs without line breaks—while employing the stylistic and rhetorical devices of poetry.”

This all by way of preamble to two new Asian-Canadian collections, neither of which, it must be admitted, clarify the issue much. One might think the difference could lie in the length, but some poems are as long as some short stories. One might think that poems are not, on the whole, narrative, but several of these tell stories. One is left feeling, in the end, that poetry is as poetry does.

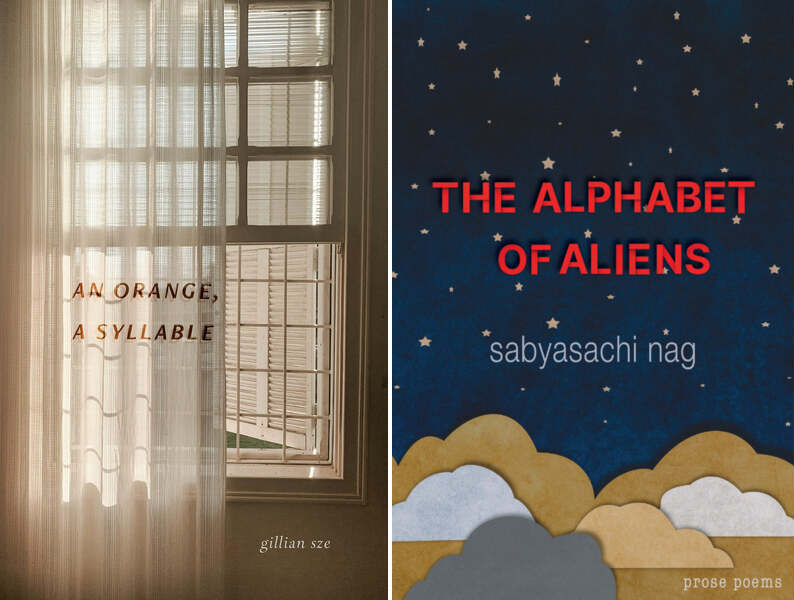

Both volumes are characterized by thematic and even narrative coherence to a far greater extent that is typical of poetry collections. Gillian Sze’s An Orange, A Syllable starts with a newborn’s first utterances and continues through to contemplate—and interrogate—motherhood, language … and art. The “aliens” in Sabyasachi Nag’s The Alphabet of Aliens are immigrants.

Sze’s poems are short, usually just a few sentences. Many contain both a point or an observation as well as hint at a story:

֦我想你 (wǒ xiǎng nǐ). In Chinese, I miss you, is straightforward. At least it seems. Three characters, one for each English word. But “to miss” is a slippery verb. In Chinese, xiang is associated with other verbs so I miss you is also wrapped in I want you / I think you / I believe you / I wish you / I suppose you / I feel like doing you / I would like you. The word’s heap holds us under.

“What is it like to be in the middle of a word?” she writes elsewhere.”It is like an open door.”

While each poem stands alone (although some lead directly into another—rather as stanzas might have had the format been different—creating episodes), the collection has, if not a narrative, then at least an arc. “My home brims with child,” she writes.The titular “orange” appears in

An orange, halved. This is for you. The child eats each half like a whole thing. Disregards each pocket crescent. The child does not care. It’s all the same. All just orange. Even the word in her mouth is all one thing, each syllable an indiscernible wave. The r isn’t obvious or heard but it’s all orange in the word and in the pulp mashed between the teeth. What’s left drips through fingers. Citrus in the air. The echo of a peel.

This ability to simultaneously experience emotion and dispassionately observe and analyze runs through the collection.

Poems about the unnamed child intermingle with those about language, Chinese and English, but also of Flaubert and Diderot. These give way towards the end (perhaps childraising had been a bit too much) to musings about art and artists: Malevich, Albers, Munch, de Kooning, Hammershøi.

Sabyasachi Nag’s shortest poems are as long as Sze’s longest—a number of his tip over onto a second page—and far less literal. And where Sze is direct, Nag oblique and obscure. One of the most straightforward poems begins:

The long night we landed we listened to the cicadas mistaking them for crickets. In complete submission—everything seemed perfect—the kind of listening that dissolves doubt about borders, limits—like that day my father died, and I realized, in the last stage of man there is no man, just a bag of unspeakable words. The sky stoops down like a heavy song. Takes it all. A single mound of cloud in the darkened sky moulded like a face. In a flash, he was gone. And we that had just arrived in an enormous plane, looking down into the clouds, were left with barf bags filled with the ash from looming infernos…

One senses something informed by the autobiographical here.

Later, when I was drained looting the last of the discarded baguettes from dirty dumpsters behind the health food grocery, a voice woke me from the deep concentration it took me to arrange them according to degrees of decomposition… But there are worms in that dirty baguette, I said. Stop stealing, someone said… But to be hungry is one thing and to be cheated of a perfect baguette by your own head is quite another.

But the poems are almost hallucinogenic—“sugar ants” occur as a metaphor more than once, as in “Models of Migration”:

Sugar ants from sunset bring bad luck reflected in old mirrors; troubles echoed in hoarse bells inside whitewashed temple domes; debts that inhabit the marrow of history; hunger that lives inside guts like feral dogs howling forever.

Sugar ants from sunup bode better: for repayment of debts; from down south they bring gold, silver; from up north they bring winds that drive the river down to the milk of estuaries. That’s what they say. What do I know? I was taken by the winds and trapped in ant colonies since 1763.

Prose poems often find their way into other collections; entire collections of them is a different experience. Sze’s selections are in length and compactness, the more recognizable as poetry (and not all are configured as prose poems). Nag’s are heavily weighted with imagery, metaphor and repetition. The contrast, and general coherence, should help those unused to the form get a feel for the potential and opportunities—if not, necessarily what definitively places these in the poetry rather than the prose bucket. At the end of day, that’s not what matters.