The Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, never one to shrink from a challenge, visited Gobustan in Azerbaijan for two decades to prove his theory that the ancestors of today’s Scandinavians left behind the mysterious rock carvings near Baku. Uncanny similarities between petroglyphs showing the long, oared boats of Caspian seafarers and those of the Vikings, and between other rock carvings in both Azerbaijan and Norway tantalized Heyerdahl.

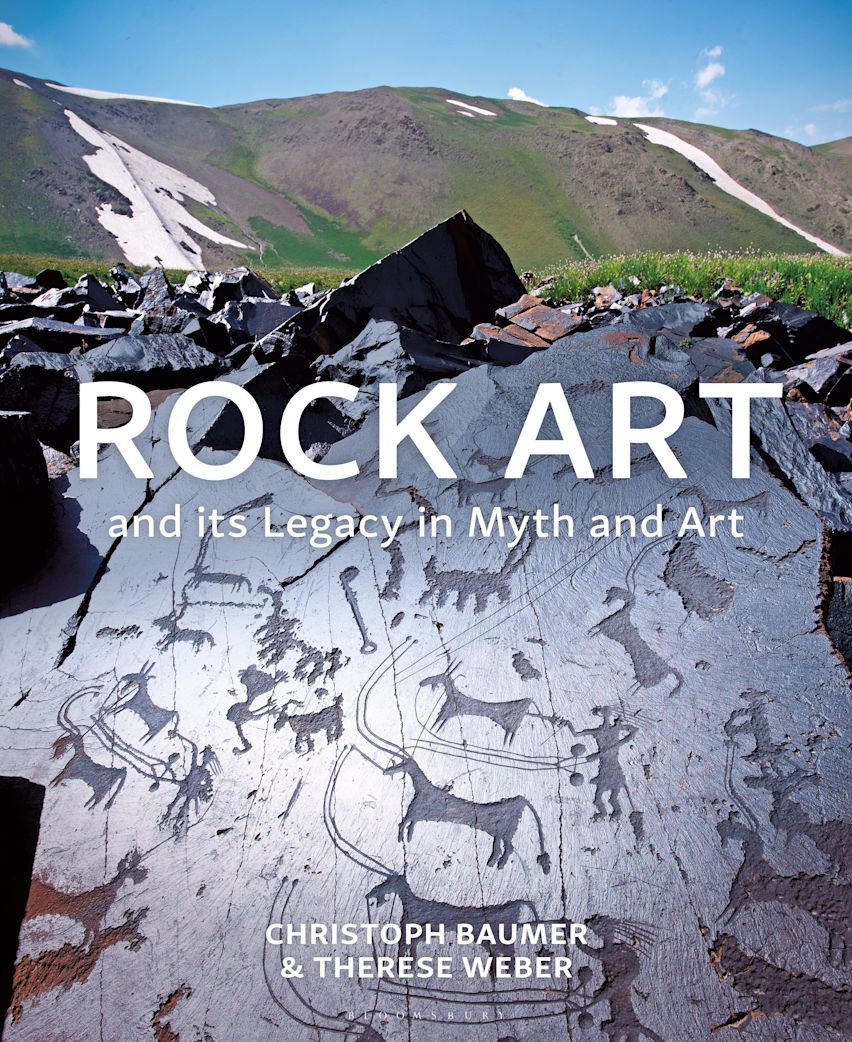

Christophe Baumer and Teresa Weber convey a similar sense of wonder in their new survey, Rock Art, which includes the famous Gobustan glyphs. Indeed, they have visited all the main sites with rock carvings across Eurasia and North Africa seeking answers to the same questions posed by the Norwegian: who made them, when, and what was their purpose? In their quest, though, they deploy more scientific rigor and less of Heyerdahl’s romantic imagination.

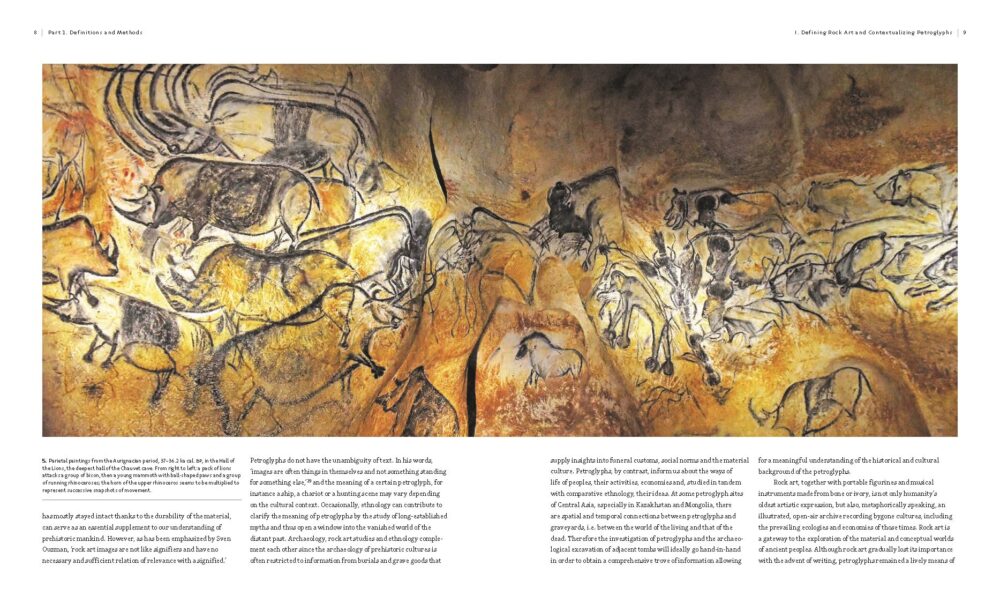

Because of the constraints imposed by the medium of carving or scratching in rock, art from across three millennia share a common aesthetic, which is beautifully captured in the striking photographs in the book.

Curiosity about these mysterious witnesses to the past has its own ancient history. The earliest record of such art come from a Chinese scholar of the Warring States period Han Fei (韓 非), who gave precise descriptions of still identifiable sites across today’s Inner Mongolia. In the 18th century, the Swedish explorer Strahlenberg published rock carvings that he had found on his freshly-delineated frontier between Asia and Europe, the Ural mountains. Rock carving art is significantly younger than rock painting. The former dates mainly from 10,000 years ago. The earliest known pictorial representations are painted, not carved, and are found not in northern Asia but on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, dating back 40,000 years ago. We do not know why, but after the last ice-age, rock carving became the dominant mode of artistic expression.

Nor can we discover much about who made the earliest rock carvings. Their sites can tell approximately when they were made, as changing climate and shorelines determined where our ancestors could settle. The hardy carvings provide an almost indelible record of our migrations. In addition, they provide much information about the changing lifestyles of the artists: from hunting reindeer and camels, to hunting on horseback and dueling with sophisticated weapons.

Baumer and Weber tease out additional stories from the stones. In Mongolia, for example, they find burials with horse bones, but no deer, while nearby stand deer-carvings, with no horses. This may testify to the co-mingling of Indo-Iranians and Altaic people and their respective cults. Later, the homogenous “animal style” emerges, which later shapes beautiful Scythian gold, as well as steppe stelae. Still later, animal style art gives way to graceful carvings of Buddha and bodhisattvas. Because of the constraints imposed by the medium of carving or scratching in rock, art from across three millennia share a common aesthetic, which is beautifully captured in the striking photographs in the book. Readers of Baumer’s previous books on Central Asia and the Caucasus will not be disappointed.

Another example of rock art progression over time is provided by the Himalaya region. The mountains host remarkable works from the bronze age to the period of Buddhism’s flourishing, and further testify that, far from being a barrier, the region acted as a highway in both directions, from the steppes to the subcontinent and back. The many acres of rock faces confronting travelers and pilgrims invited them to leave traces of their beliefs and customs. The dense traffic resulted in palimpsest superimpositions of cultures in many sites, visible today by intrepid tourists.

A final example of how these rocks speak to us comes from Heyerdahl’s stomping grounds in Azerbaijan. The Gobustan area is particularly rich in rock art as peoples settled by the ever-changing coastline of the Caspian Sea, over a period of 17,000 years. We can read the coming and going of prehistoric fauna. Between 10,000 and 4,000 years ago the “viking” boats, carrying as many as 20 passengers appear. The boats had rowers, but no sails. Today we know that they did not migrate to Scandinavia as Heyerdahl argued; rather they were expressing the importance of seafaring in their culture, an element they shared with the ancient Norwegians.

Baumer dismisses many other fanciful explanations of the ancient rock carvings, on the grounds that we know very little about the societies and the belief systems that produced them. We must be content with the insight that our earliest ancestors were capable of producing remarkable works of art. To learn, for example, that the population responsible for the great cave paintings of southern France included as few as 1,500 individuals, suggests that there were many more Matisses per capita 40,000 years ago than in the 20th century.

The aesthetic achievements of this ancient art are further illustrated by the authors’ survey of Arabia, Europe and north Africa, while a closing essay by Therese Baumer further explores historical approaches to rock art, elements and techniques that provide further clues to its significance, and how rock art has influenced contemporary artists, including Paul Klee. Both the high quality photographs of archeological sites and of contemporary works of art inspired by them (many by Weber herself) make this edition simultaneously a beguiling coffee table book and a good text-book style introduction to the subject.

The accumulated evidence of the photographs, their vast geographic and chronological distribution, and the high quality of their craftsmanship show us just how pervasive and significant this early branch of art is.

For students, Baumer is rigorous and methodical in explaining the context for these beautiful photographs. He discusses climate change as a major driver of migration as well as an important element in dating the carvings. Dating also involves a good deal of chemistry, for which Baumer delivers a solid primer. Discoveries in ancient DNA, both human and animal round out the scientific and academic side of this story. Finally, theories from anthropology and art history are evoked to enhance our understanding of the meaning of these images.

More than anything else, the accumulated evidence of the photographs, their vast geographic and chronological distribution, and the high quality of their craftsmanship show us just how pervasive and significant this early branch of art is. Even if Gobustan does not evidence ancient migrations between the Caspian Sea and Scandinavia, readers of Rock Art will never again look at their ancient scratches in the same way.

You must be logged in to post a comment.