Once upon a time, “storytellers” (who predate writers by a great margin) were respected members of the communities they served: entertainers, yes, but also playing a crucial role in preserving memories and lore by retelling old stories and creating new ones. If the blood of this tradition doesn’t actually run in Subi Taba’s veins, she is at the very least a vehicle for its spirit.

Tales from the Dawn-Lit Mountains, she writes in the acknowledgments

is a souvenir of my life in the hills. I was born in Arunachal Pradesh, a state resting in the lap of distant, impenetrable mountains of the eastern Himalayas. The stories in this collection are shaped by the hilly terrains of Arunachal Pradesh, stirred by the mountain rivers, flavoured by the harvests of the soil and tempered by the tribal people living in the isolated hinterlands under the shadows of magic and realism.

The stories are not so much “about” tribal people as “from” them, or at least it feels that way. Underlying the stories is a world of tribal feuds, shamans and headhunters, ghosts, curses, spirits of plants as well as animals and people, hornbills, magic pythons and vengeful tigers, poisoned arrows, mountains, forests and rivers. Conveying this world from the inside rather than voyeuristically is no mean feat, but Subi Taba writes with aplomb.

The trail of my macabre memory floats with the heavy, steady flight of the oldest living eagle in our village. It stays hidden in the heart of the hollock grove beneath our village hills. The tattoos etched on my body are the cartography of my killings. The miniature brass heads adorned in my necklace are the totems of a prized warrior. A headhunter.

As the collection progress, into this world which exists largely outside time, Subi Taba begins to introduce more modern elements, an American missionary, village schools, buses (as seen through tribal eyes):

Across the serpentine pathway, a gigantic box-like structure was crawling and honking. It came to a screeching halt amid a thick swirl of dust. Humans carrying small bags and baskets ran towards it…

as well as provincial officials; smartphones and even WhatsApp.

Subi Taba can be tender as well as graphic and violent. A widow, still young, remembers her husband:

The ghosts of the past crept into her dreams like a silent scuttling spider with beady eyes. She and her husband are newly married, alive and breathing together inside a boathouse floating on a small lake. It is nighttime. The waterfowls have stopped quacking, the frogs have stopped croaking, and all the worldly distractions have slunk away like unattended lovers… Below their bed, under the web of reeds and water hyacinths, the fish are eavesdropping on their conversations and swim away mouthing bubbly poesies to each other under the faint glow of the moonlight.

She is also a dab hand at satire, as in “Python Man” (which reads rather like a tribal take on the Brothers Grimm’s “Seven at One Blow”) in which a man who find a dead giant python and taken credit for killing, becomes a social media sensation, only to be come up against conservation regulations (better those, however, that the spirits of dead animals which plague humans in other stories).

It’s not that there is no politics in the collection, but it is rarely overt. There are some unctious officials, but most of oppression and violence is intra-tribal rather than something from outside. Her point, if she is making one, is holistic.

The collection ends with “A Man from China”, perhaps the most traditional story in the collection in that it contains no magic realism at all. A local man found himself long ago on the other side of the border and ended up settling down in Tibet and marrying a local girl who “looked like a white lotus in the breeze”, with whom he has a daughter. He is jailed for, in effect, not having papers; once he is out, he finds his wife had married his best friend and had a son. He decides to return to Arunachal Pradesh, crossing by way of “the snow-capped ranges of Mount Namcha Barwa, with its sharp edges jutting out towards the sky.”

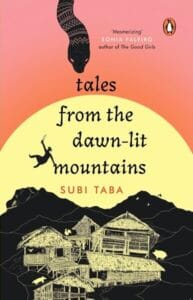

There is not much to fault in this wide and varied debut collection. The opening story ”A Night With The Tiger” which is, presumably, the earliest, is the least polished despite nevertheless having won the New Asian Writing Short Story Competition in 2020. They stories get progressively (even) better. The use of footnotes in fiction is usually something to be avoided, and there are more than a few here, perhaps unnecessarily since the author elsewhere makes the meaning of local terms clear in the text. The rather striking black and white illustrations are perhaps unnecessary; her powers of description suffice.

Subi Taba is a strong and original voice with evident empathy with her characters and sympathy with their tribulations. Her evocation of a pre-modern time is reminiscent of Alexander Grigorenko’s novels of the Siberian taiga. Perhaps she’ll turn her skills to something longer and even more immersive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.