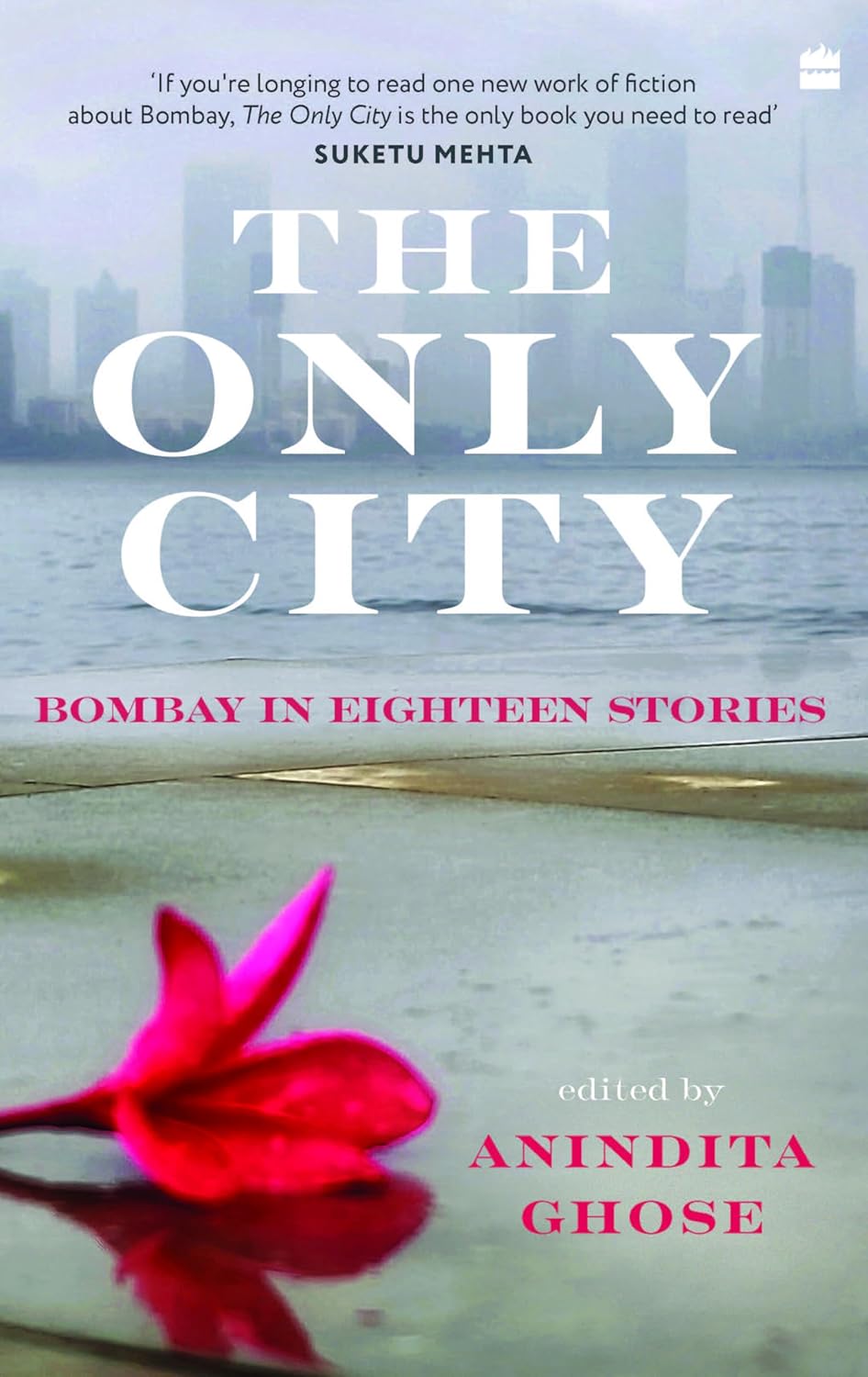

I was born in Bombay and lived there, not far from the Gateway of India, for the first sixteen years of my life. I left the city by the bay soon after turning sixteen. When I returned decades later, I barely recognised it. The city and I had both gone through dramatic changes in the interim. So it was with real anticipation that I picked up The Only City, an anthology of stories about the city of my birth, edited by Anindita Ghose.

I didn’t know most of the contributors, so I had no fixed expectations. In spite of my jadedness about Bombay, I found myself grappling with long-dormant emotions while reading some of the stories, a testimony to the power of the words.

Bombay is also a city teeming with writers seeking “inspiration”.

Yogesh Maitreya’s “The Sound of Silence” is the most lacerating. A Dalit who came to Bombay like millions of others—chasing dreams, chasing dignity—he almost lost himself in the haze of cheap ganja and cheaper liquor. The city swallowed his voice. Only when he moved to Hamburg did the silence arrive: real silence, the kind that lets a man hear himself think for the first time. From that distance he writes about the futility of Indian academia for someone of his caste and circumstance—how universities offer theories of resistance but no actual shelter—and about the daily nihilism of migrant life in Mumbai.

Conversely, Tejaswini Apte-Rahm’s “Nurse Shanti” is quiet, masterful, and heartbreaking. A village woman fakes her way into a plush job nursing an ageing Parsi gentleman; on the side, she stores illicit goods for a shady aunty to save for a better life in Dubai. Apte-Rahm refuses to judge either the forgery or the greed. Instead she gives us the slow, improbable tenderness that grows between employer and employee, and then the sudden, tragic unravelling. You close the story feeling you’ve been inside someone else’s skin for twenty eight pages..

In the most unflinching story in the book, Lyndsey Pereira’s “Strays”, a railway-platform urchin survives hell, and when mysterious men with heavy bags later detonate bombs across the city, the boy watches the explosions while sipping cutting chai, feeling grim satisfaction that someone, at last, has taken revenge on his behalf. Jeet Thayil’s “The Meat in My Hands”, on the other hand, imagines a near-future Mumbai where religious fundamentalism has banned meat; it’s traded like heroin, and the addict chasing it feels suspiciously like the one Thayil chronicled in Narcopolis. His dystopian city requires no great leap of imagination; it already looks like one vast slum.

Seen through a little girl’s eyes, Prayaag Akbar’s “Hoodbhoy House” is excruciating. Her ad-man father enrolls her in an elite school to network with the super-rich parents; the casual cruelty of the rich kids, the whispered reminders that she doesn’t belong, are rendered with a child’s bewildered exactness. Innocence makes the class war sharper.

Bombay is also a city teeming with writers seeking “inspiration”. In his noirish tale, “Where The Lights Never Go Out”, Jai Raj Singh sends a screenwriter into a brothel. only to be told by the madame that he doesn’t belong: “you have strayed into a place where broken men come to exorcise their demons and cauterise their wounds. They drift in to lick the flames of pleasure, only to be burnt and consumed.” Manu Joseph’s “Sufficient Magic” shows a presumably younger version of the author asking the question that has always obsessed him: is there anything larger than this grubby, material world? He stalks scientists at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research looking for proof of the supernatural, the unexplainable, God in the equations. The story is clever, funny, and finally shrugging: maybe the only magic is the sufficient kind.

Namita Devidayal’s “The Girls of Visty Villa” and Shubhangi Swarup’s “Snakeskin” are beautifully written—elegant, decorous, fragrant with old Parsi money and ecological lyricism—but ultimately weightless, floating high above the city’s stink. Ranjit Hoskote’s “The Painter’s Last Stop” is enjoyable not for what it says about Bombay but for the dazzling way the ghost of a dead artist weaves Indian mythology, philosophy, art history, and both world wars into one stream-of-consciousness rant. Pratyush Parasuraman’s “Two Bi Two” is about cruising for gay sex on Bombay’s filthy, steaming local trains, a fate I would not wish on my worst enemy.

These writers keep the Bombay I once knew stubbornly alive

As is often the case with anthologies, some stories pass with less impact. Editor Anindita Ghose’s own “Normal Neighbours” feels oddly bloodless given its pill-popping, wife-swapping setting. What struck me early, though, was how many of the voices belonged to the Ivy-educated or foreign-resident Indian elite. Unlike anthologies I’ve loved about Lagos, Cairo, Jakarta or São Paulo—where the writers are usually steeped in the city’s dust and noise—many of these authors felt almost like detached outsiders looking in. That, of course, is par for the course in Indian writing in English. By contrast this year’s International Booker went to Banu Mushtaq, a writer unlike most here, whose collection of stories about the lives of Muslim women in southern India, Heart Lamp, had to be translated from Kannada into English.

Yet taken together, these writers keep the Bombay I once knew stubbornly alive: a whore at the end of the day, not particularly beautiful or alluring, but one who’ll tell you every last fascinating story she knows for the price of a drink and a joint. You’ll swear you never want to see her again—because she’s honest to a fault, and from a whore you expect at least the mercy of a little artifice

Bombay never pretends. And this anthology, for all its unevenness, refuses to let her.