The recent documentary, The Sea is Our Home immerses viewers in the vibrant yet precarious world of the Bajau Laut, whose stilt houses rise above the turquoise waters of Sabah’s east coast. While this film is centered on the sea nomads of Malaysia, the Bajau Laut can also be found in aquatic settlements across coastal Philippines and Indonesia. The camera lingers on Tetagan’s stilt houses, built from pandanus leaves, which are more than mere resources—they’re tied to the sacred, embodying the community’s spiritual connection to the Lady of the Forest and the Lord of the Sea. We meet Bidan, a midwife who carries forward ancient birthing practices, and Nasiri, a healer and fisherman whose life reflects a profound bond with the land and sea. These figures ground the film in a sense of heritage, their stories echoing myths of a princess seeking refuge, a narrative that resonates with the Bajau Laut’s ongoing search for sanctuary.

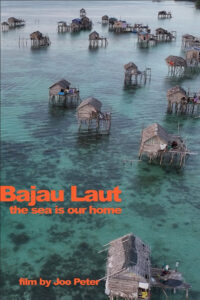

Joo Peter, a German filmmaker and academic from Stuttgart, brings his evocative lens to Bajau Laut: The Sea is Our Home (2025), his second exploration of Southeast Asia’s Indigenous cultures after Mentawai: Souls of the Forest (2023), which illuminated the spiritual and environmental struggles of West Sumatra’s Mentawai tribes. With lush visuals and intimate storytelling, this documentary captures the beauty of their ocean-bound existence while laying bare the harsh realities of systemic marginalization. Peter crafts a narrative that feels both deeply personal and urgently universal, capturing the cultural richness and spiritual depth of a people fighting for their place in a world that often denies their existence.

On 4 June 2024, massive raids leveled indigenous villages in Tun Sakaran Marine Park, a popular tourist and diving destination, leaving families displaced and communities shattered. The film unflinchingly documents the destruction of stilt villages, with Tetagan’s ruins serving as a haunting symbol of state-sanctioned erasure. Peter captures the aftermath through the testimony of a surviving family, their words heavy with loss but defiant in spirit. The Malaysian government, particularly in Sabah, has targeted Bajau Laut stilt villages in areas like the Marine Park, citing illegal settlements and environmental degradation as justifications for demolitions. These actions reflect a broader state agenda to regulate maritime spaces for tourism and commercial fishing, often at the expense of the Bajau Laut’s ancestral claims to the region, which are dismissed due to their stateless status. Additionally, security concerns, including fears of cross-border activities in the porous Sulu Sea region, have led to crackdowns on these communities, who lack documentation and are thus viewed as potential threats, further exacerbating their marginalisation.

The Bajau Laut are stateless.

The Bajau Laut are stateless because modern nation-state borders, created after colonial rule, divided their traditional maritime territories, leaving them outside the legal framework of any country. Their nomadic, sea-based lifestyle meant they weren’t always tied to a fixed land or nation, making them “ungovernable” and undocumented. This compounds their vulnerability—without citizenship, they often lack access to state schools, healthcare or many legal protections.

Amid this hardship, the film finds hope in the tireless work of activists. Pacik Khalid, a seaweed farmer and artist, stands out as a catalyst of change. He founded Tetagan’s first school for stateless children 17 years ago, later appearing as a theatre director and costume designer at Semporna’s Lepa Festival. His multifaceted role highlights how art and culture become tools for survival and advocacy. Similarly, the Borneo Komrad School in Semporna’s Bangau Bangau and an alternative university in Air empower stateless youth through education and community work. Students create woodblock prints inspired by Pangrok Sulap, a collective whose Kinabalu studio Peter visits, showcasing art as a form of peaceful rebellion. These initiatives are lifelines, offering children a chance to learn and dream despite constant harassment from authorities.

The film’s portrayal of Omadal village adds another layer, showing a community in transition with tin roofs replacing traditional materials. A custodian of spirits, cooking seashells while describing the interplay of female and male jinn, reveals the enduring mysticism of the Bajau Laut. Meanwhile, the bright yellow Iskul Omadal school buzzes with life as children climb from the sea to its platform, dancing to Pangrok Sulap’s music and engaging in learning. These moments of joy are fleeting but powerful, underscoring the community’s determination to thrive against the odds.

The visuals never overshadow the human stories.

Peter’s cinematography stands out, capturing the shimmering sea and sprawling stilt villages with a reverence that mirrors the Bajau Laut’s own connection to their environment. The long walkways of Semporna’s seaside villages, home to over 30,000 people, create a mesmerizing maze that draws viewers into the heart of the community. Yet, the visuals never overshadow the human stories. The film’s pacing, at 75 minutes, feels deliberate, allowing each voice, whether a healer, a student, or an activist, to sink in without rushing their truths.

Bajau Laut: The Sea is Our Home is a call to witness and act, celebrating a people whose roots run as deep as the sea they call home, even as they face an uncertain future. Peter’s lens, capturing both the beauty of their culture and the stark reality of their statelessness, compels viewers to confront the human toll of political neglect and to recognise the Bajau Laut’s enduring claim to their place in the sea they call home.

You must be logged in to post a comment.