The opening panels of the manga Miss Ruki show the title character working from home processing medical insurance claims. In a voice so dry it verges on sardonic, an unseen narrator explains that Miss Ruki finishes projects weeks earlier than her boss thinks she does, so she spends most of her time reading books from the library—books like Saeke Tsuboi’s anti-war classic Twenty-Four Eyes or Ira Levin’s classic American horror novel Rosemary’s Baby.

Miss Ruki’s foil is her best friend, Ecchan. Ecchan is one of 1980s Japan’s prototypical “OLs”—a member of a generation of “office ladies” with well-paying jobs, ready to spend her independent income on a host of consumer goods available in the capital city of the world’s second-largest economy. She’s constantly shopping. She wears trendy fashions. She eats at hip new restaurants.

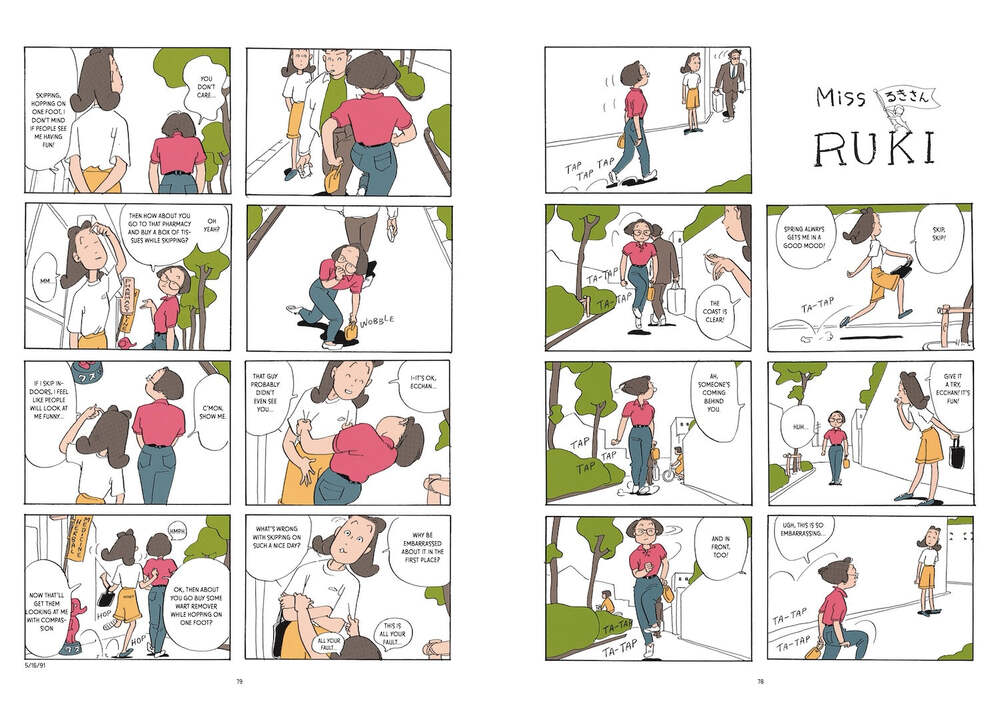

“I don’t want to eat anywhere that requires nerve,” Miss Ruki counters. In contrast to Ecchan, Miss Ruki is phenomenally uncool and completely unconcerned about it. She’s unusually clumsy, but nonchalant about personal injuries—anyone who reacts to injuries with tears “has rarely fallen down in their life,” she reflects. She wonders what it would be like if she spent entire days in the bath. She borrows books from the children’s library. She skips down the public sidewalk. And she changes her wardrobe so rarely that, as Ecchan laments, “it’s like time has no effect on her.”

Miss Ruki is more like a Sunday comic strip than a graphic novel.

Fumio Takano’s Miss Ruki doesn’t look like most manga translated into English. In fact, it’s more like a Sunday comic strip than a graphic novel. English-language readers are most familiar with shonen manga—titles like Naruto, One Piece, and Dragon Ball that highlight friendship and adventure and tend to be drawn with a signature style marked by boyish-looking male protagonists with notably stylized hair. Most shonen stories in translation involve long story arcs and are published as what an English-language publisher might call a graphic novel. Shonen is the most popular of the four main categories of manga, named by the age and gender to whom they are marketed—shonen (boys), shoujo (girls), seinen (men), and josei (women). Historically speaking, publishers have struggled to get Anglo-American readers interested in non-shonen titles and many translated volumes have languished on bookstore shelves.

Miss Ruki is not a shonen title. But neither is it shoujo, seinen, or even josei. As Alexa Frank explains in her translator’s note, Fumio Takano was one of the most important artists of the joujinshi or “self-published” manga movement—a set of work that challenged the manga industry’s neat, gendered marketing categories.

Takano published her loosely-related, episodic strips that appeared more-or-less monthly in a popular women’s magazine. The artwork is more reminiscent of Charlie Brown, Little Lulu or even Curious George than what is generally recognized by English-language readers as “manga style”. The coloring, too, is offbeat and not even standard from run to run. (In one episode, Miss Ruki’s hair is gray; in another, blue-black, and in a third, bright red.)

Miss Ruki has a timelessness all its own

Originally published from 1988-1992, Miss Ruki can feel like a period piece. Ecchan’s spendthrift behavior and distinctly 1980s OL attitude have long been a thing of the past. Each strip is dated at the bottom of the page. A few helpful footnotes, such as one about a popular 1989 TV drama, also keep even readers unfamiliar with the manga’s cultural context rooted in the moment in which the manga was written. Later strips reflect Japan’s economic decline. For example, in a November 1991 strip, Ecchan reads work by Marxist economist Hajime Kawakami. (The friends go on a shopping spree in the next strip, published in February 1992.) Soon, Ecchan buys herself eel to compensate for a reduced annual bonus. By late 1992, she comments to Ruki that it , “Seems like the economy’s in real bad shape.” In singular Ruki fashion, Ruki answers that she’d rather “pinch pennies” than work any harder, even in a bad economy—even if it means selling everything in her house.

Even though Miss Riku is, in many ways, a product of its time in a medium less familiar to English-language readers, it also has a timelessness all its own. Those who are willing to live outside of what society dictates make for memorable characters, as do characters who can fall down and keep getting up again. Time, as Ecchan notes, has no effect on Miss Ruki.

You must be logged in to post a comment.