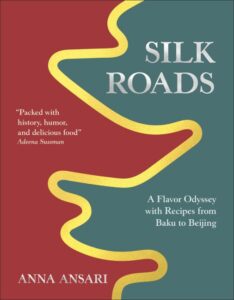

In Silk Roads, food writer Anna Ansari connects areas and cuisines not typically associated in English-language cookbooks, traveling from Beijing, to Baku in Azerbaijan. The closest author/chronicler would perhaps be Paula Wolfert, who is known for her Mediterranean cookbooks spanning France, Morocco, and the “eastern Mediterranean” to include Turkey. Ansari’s food memories originate from her ethnically Turkish family who left Iran and settled in the US. In a particularly visceral memory, her father tried to bring a rare melon back to his family from a work trip to Uzbekistan:

a fruit so singular that all he wanted was to bring it to his children. So that they could taste this golden melon of Samarkand, if you will, he hand-transported it across the world, a treasure, a tribute to my siblings … Like ships stocked with citrus to ward off scurvy, camel caravans travelled across Central Asia laden with strips of dried melon, pregnant with sweetness, vitamins and the taste of home, comforting and nourishing their human members on their long journeys.

Later, Ansari travels to Beijing as a high school exchange student and, setting aside Americanized Chinese ideas of the cuisine, slurps up Uyghur noodles.

I didn’t know it then, but when I had that oh-so-memorable bowl of Uyghur noodles in that alleyway in Beijing’s Ganjiakou neighborhood, I was eating a microcosm of history. I was eating millennia worth of influences, traditions, stories, memories, connections, and culture. I was eating a story of trade, of travel, of homesickness, of assimilation, of belonging, of everything, everywhere, all at once. And 25 years later, in a village in Uzbekistan, a woman with whom I had perhaps little in common save our love of noodles and familiarity with a Romance language, taught me to make those noodles—or some variety of them, anyways. I share that knowledge with you, along with other noodle dishes of the Silk Roads, all related through either flavour, method, history, or culture, and, like everything in this book, all delicious.

This initiation into new foodways sparks later journeys that coalesce into this book. Unlike most cookbooks, the small text can be difficult to discern on pigmented pages, making it a bit harder to follow for cooking, but pleasant as an immersive travelogue. While on modern cooking websites, we might “jump to the recipe” to avoid the preamble, I’d recommend against it with Ansari:

We were waiting for the goat when they brought out the yogurt. Little tubs filled with a white, dairy-looking substance, sprinkled with rock sugar. It was delicious—and not just because we were hungry. Cultivated and prepared by the same Tibetan villagers who would soon toss a caprine quadruped on the bonfire before us, it was cold and fresh and tasted of the farm, of the Gansu grasslands on which we stood. But it wasn’t goat yogurt. Nope: it was yak yogurt. Yes, you heard me right-yak yogurt. Yogurt from that hairy, horned ox associated mostly (for me at least) with Himalayan sherpas and yak milk tea, a beverage so far removed from what I consider tea to be, that I cringe even thinking about it. I will be content if I never have a sip of yak mild tea again in my life, but disappointed if I never enjoy another spoonful of yak milk yogurt. After the yogurt and some beers and a few dances around the bonfire, the goat materialized—and it dazzled us. We pulled the meat directly off the bone, earring it with our hands as the Milky Way spilled itself across the sky.

Fortunately, most recipes do not call for extra effort by the home cook to include a bonfire or a whole goat, but they might inspire someone adventurous to buy some new spices or put familiar items together in a new way. The collection of these areas together, which she loosely calls “Central, East, and Middle East Asia” feels like a reclaiming inversion of the Edward Said concept of “Oriental”.

For an American accustomed to the Johnny Appleseed story and the tradition of apple pie, it is revelatory to hear the even earlier history of how apples spread over the world.

There are over 7,000 apple varieties grown in the world, of which nearly 3,000 are grown in the UK. Ditto the United States. Every single one of these apples—Pink Lady, Bramly, Walthanstow Wonder, Cox, unnamed garden apples, wild apples, lost apples, you name it—all of them originated in the very same place: an ancient forest in the Tianshan Mountains, somewhere near the China-Kazakhstan border. Right smack dab in the middle of Silk Roads territory, a veritable garden of Edena, an ancestral home, a lao jia from which apples spread across the globe … The seeds turned into saplings turned into fruit-bearing apple trees, and the process repeated itself, with bears eating and spreading apple progeny further and further from the initial forest. And man eventually tasted this fruit, loved it, planted it, harvested it, shared it, traded it, travelled with it. And baked it into a pie. No fruit is more emblematic of food, flavours, and ingredients than the humble apple. And no dessert is more associated with the United States than the humble apple pie.

For a peripatetic cook or traveler, Silk Roads is a welcome inspiration and escape.

You must be logged in to post a comment.