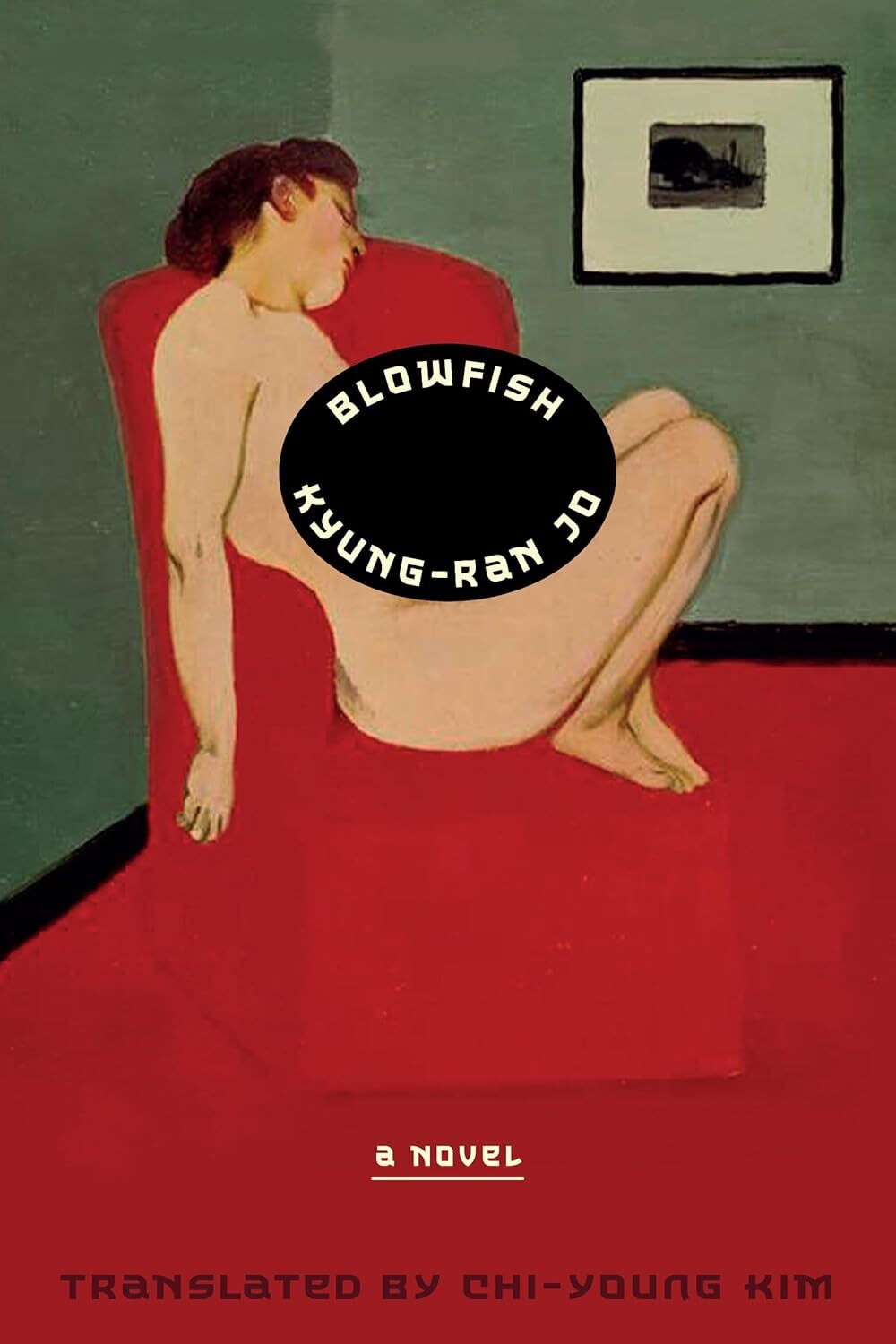

In Kyung-Ran Jo’s Blowfish, two people flirt with death in their own traumatic ways, only to find themselves slowly entangled in one another. Translated from the original Korean by Chi-Young Kim, the novel unfolds through alternating perspectives and flits between Seoul and Tokyo. Blowfish privileges atmosphere over plot, unfolding as a moody and cinematic meditation on the slow ascent from the depths of depression.

Of the two unnamed narrators, one is a female sculptor who believes that death has been haunting her family for generations, and soon it will lay a cold hand on her shoulder and nudge her toward suicide. Determined to meet death on her own terms, she plans to prepare a bowl of blowfish soup—toxins and all—intending to follow the same bitter path as her grandmother who also drank blowfish soup and died before her father’s eyes. Not only is the sculptor is now haunted not only by this family “legacy” of suicide, but also by fleeting visions of her grandmother’s ghost, appearing in her apartment or perched atop tree branches. To deal with her ghosts, the sculptor packs up her apartment and leaves for Tokyo under the guise of attending a residency and finding new inspiration.

Yet her true motivation is Japanese blowfish.

She had realized that she, like her father and his siblings, had grown tired of plodding forward in an attempt to avoid death … All she had done was move herself from this side to that. She had merely chosen a different world.

The man she meets, an architect, spends his days resisting thoughts of death. After his brother committed suicide, the architect’s family has been consumed by an unshakeable grief, stagnant and claustrophobic. Though the first encounter between the sculptor and architect occurred off the page—somewhere in Seoul, years earlier—they reunite in Tokyo and begin a relationship, in the loosest sense of the word, that stretches across years and gradually forms a bond strong enough to pull them back from the brink of death toward a liveable reality. In a novel characterised by intense inertia, their encounters serve as the catalyst for action. On his own, he wanders streets with nothing to do or think, yet after meeting her, he is seized with bouts of desire and energy.

He was afraid that the things he had just recalled, those passions, would fall to the ground, hot like candle wax, and solidify in an instant. He wanted to bang on the ground and speak. He wanted to pray.

In the absence of metaphorical “solid ground”, the architect is consumed by the desire to design an earthquake-resistant building—a pinnacle of dependability—and spends his days walking through the streets of Tokyo—and later Seoul—looking up at towers that reach the skies while pondering their shock absorption and potential casualty count. In the moments when they ponder their art—she with sculpture and he with architecture—mundane scenes are peppered with sharp insights, and readers are treated to exquisite sentences, such as “the crescent moon hung in the night sky like someone had pressed their fingernail into it.”

Blowfish follows a loose narrative structure, where chapters more often than not resemble vignettes, unbothered by the sequential constraints of the preceding scene. More questions are asked than answered, and the chapters that spend words on a setup often withhold any resolution. The narrative gaps created by this structure leave the reader suspended in uncertainty, much like the characters themselves. In their mutual recognition of a presence “clad in a long, dark cloak”, they begin to grow closer to each other in their own quiet and reserved ways, making appointments to meet and walking down Tokyo’s streets. The moments when these plans are set are the calmest of the novel—after all, if one makes a plan for the future, one intends to be alive to see it through.

Quiet and moving, Blowfish interrogates the aftermath of death through various lenses, examining the broken people left behind and questioning the stains of grief that remain. In its greatest moments, it seizes the characters with accountability, proclaiming that they are “hanging on to the specter of death” because of their own insecurities, “because you’re secretly worried that you might not be a great artist, that you might be nobody special.” Part-romance, part-tragedy, Blowfish is perhaps, at its core, a love story of those who try to keep on living.