A fluent Arabic speaker, Justin Marozzi has spent much of his career as a journalist and author trying to understand the Middle East through an historical lens. His earlier books include Islamic Empires, a history of Islamic civilisation told through some of its greatest cities, and Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood, which won the 2015 Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize.

His new book, Captives and Companions: A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World is indeed a history of slavery and the slave trade in (much of) the Islamic world—apart from passing references, it excludes India and southeast Asia. It stretches from the earliest days of Islam in 7th century Mecca and Medina to interviews with former slaves in present day Mali and Mauritania.

Wherever possible, Marozzi highlights the voices of the enslaved themselves.

Marozzi acknowledges that slavery has been almost universal, but he asks, in effect, what kind of slavery and which slave trades westerners now choose to discuss. His answers are: plantation slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. The world once contained, he sets out to explain to the general reader in the West, far more slave trades than the one they know from books and films; that in Turkey, Africa and the Middle East in particular various forms of slavery were an accepted part of life from ancient (pre-Islamic) times, until as late as 1981, when Mauritania became the last country to outlaw not only slave trading, but also the institution of slavery.

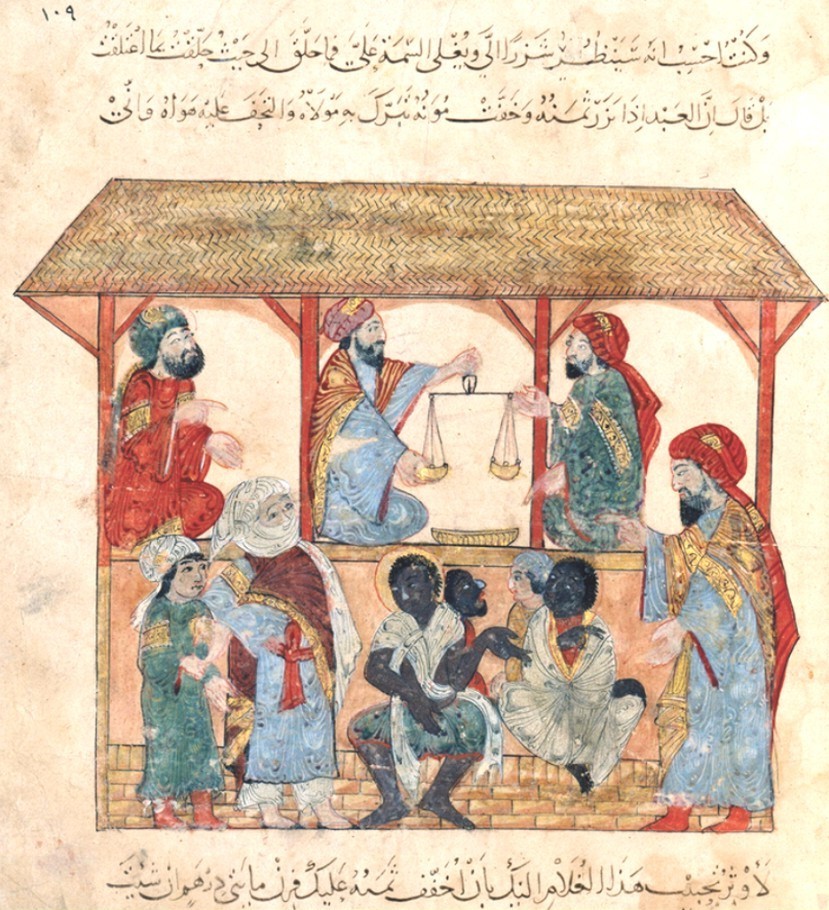

Marozzi marshals a great deal of information to produce an account which is always readable, clear, informative, and interesting. Wherever possible, he highlights the voices of the enslaved themselves, their first-person experiences and memories, notwithstanding these are generally mediated by “European and American travellers, explorers, diplomats, officials, abolitionists, journalists, editors and publishers.” Testimony is often gut-wrenching: accounts of children being snatched from parents during the terror of a slave raid; forced marches across the Sahara in which untold numbers died; women being assessed like animals in slave markets; the horror of castration.

The variety, and paradoxes, of slavery in the Islamic world are thoroughly explored. Slave soldiers, whether Mamluk, in Egypt, or Janissary, in Turkey, could become rich and powerful, as could eunuchs serving in Ottoman harems; enslaved concubines could move to the centres of political hierarchies, and become the mothers of future rulers.

Where did these slave soldiers, eunuchs and concubines come from? Yes, multitudes were black Africans, trafficked north across the Sahara, but vast numbers were white, particularly from Eastern Europe, the Balkans and the Caucasus, with some raids as far away from Islamic lands as Britain and Iceland.

Marozzi quotes Sudanese scholar Yusuf Fadl Hasan: “Slavery is slavery and cannot be beautified by cosmetics.”

Marozzi is well aware that any history by a westerner of anything contentious in the non-western world, particularly when it links the contested idea or practice to a particular religion, can run up against culturally-based objections:

The heat of nineteenth-century debates between mostly Western opponents and mostly Muslim defenders of slavery is echoed in some scholarly clashes today. The historian Dahlia Gubara, for example, argues that the very histories of slavery and the slave trade in the Middle East are so problematic that they constitute a ‘liberal incitement to racial discourse’. A key problem with such an adversarial approach is that it can easily slide into ‘nothing to see here’ denial. Some academics, meanwhile, argue that critical discussions in this field are guilty of ‘otherizing’ Arabs, Muslims and Africans.

Marozzi evidently feels otherwise and that is essential to understand slavery in the Islamic world, not least because:

its sheer scale shows that this was no fringe affair. In terms of the numbers of people enslaved it was on a par with the slave trade to the Americas. Second, it was not a short-lived business that fizzled out after a brief flourish long ago. It lasted almost 1,400 years, far longer than the Atlantic trade. And finally, it is necessary to examine it because it continues – and even flourishes – in parts of the Muslim world today, openly in some places, behind closed doors and through private messages on smartphone apps in others.

Nor was slavery in the Islamic world in some sense more benign than elsewhere. He quotes Sudanese scholar Yusuf Fadl Hasan: “Slavery is slavery and cannot be beautified by cosmetics.”

Marozzi stresses that the persistence of slavery in parts of the contemporary Islamic world cannot and should not be overlooked. Captives and Companions starts with Marozzi in Bamako, in 2020, and finishes with him in Nouakchott, in 2024. He makes it clear that despite its formal illegality, hereditary chattel slavery persists today in both Mali and in Mauritania, and that in both countries local organisations and brave activists are working to free slaves, and to bring slavery to an end. Marozzi’s interviews with three freed slaves, Hamey in Bamako, and brother and sister Habi Rabah, and Bilal, in Nouakchott, are amongst the most moving passages in the book, and deserve to be widely read.

You must be logged in to post a comment.