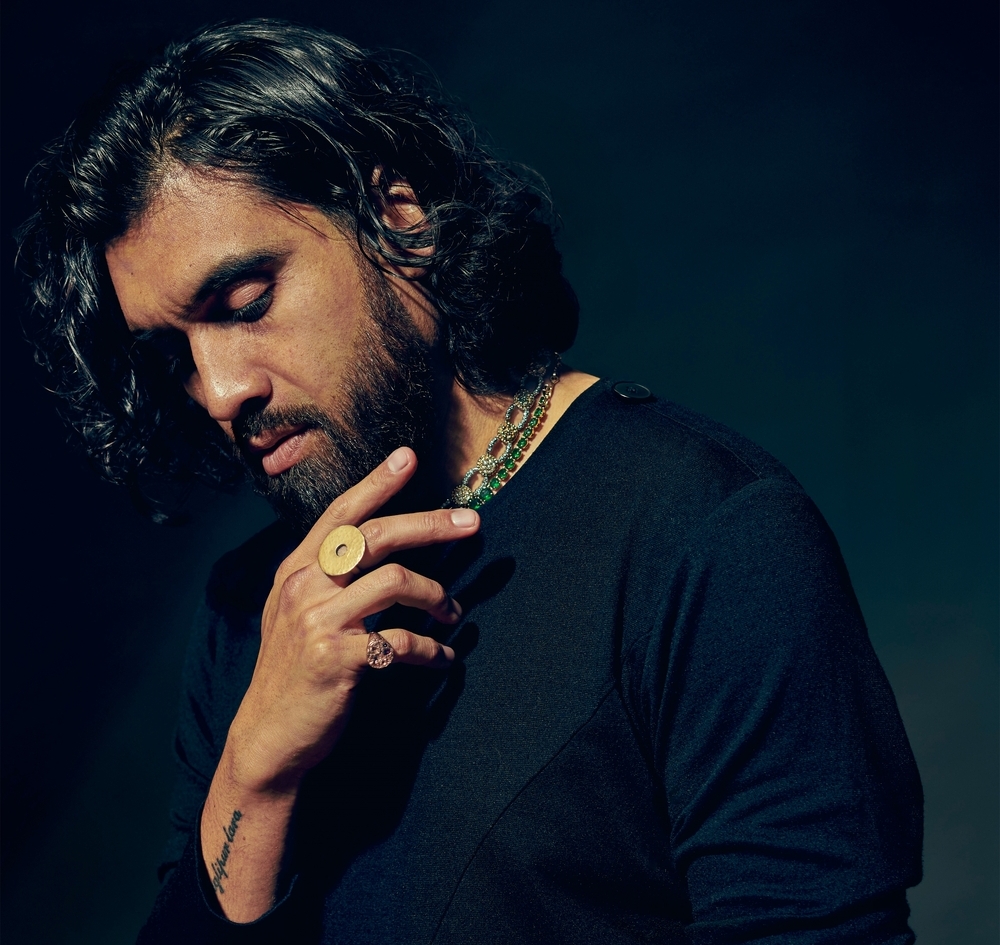

Bornean-Australian novelist, playwright, poet, rapper and visual artist Omar Musa comes with a bit of a pedigree. His debut novel Here Come the Dogs was long-listed for the International Dublin Literary Award and for the Miles Franklin Award. He was named one of the Sydney Morning Herald’s Young Novelists of the Year in 2015.

His new novel, Fierceland, is both a family saga, and an environmental morality tale for the post-colonial, late capitalist era. Most of it is set on Borneo, and it excoriates the exploitation of indigenous and local people, and as well the destruction of the rainforest.

Behind every great fortune lies a great crime. In 1988, Yusuf began logging the Bornean rainforest, and took his children upriver to witness the start of the destruction. By the time of his death, in 2018, he is a palm-oil baron, and one of Malaysia’s wealthiest men. His now-adult children are living abroad. Daughter Roz is an artist in Sydney. Harun is a tech entrepreneur in Los Angeles. They both return to Borneo to attend Yusuf’s funeral, and to confront the past: back in 1988, they witnessed more than trees being felled; they witnessed, too, their father’s henchmen beating a local man, Salam, who had attempted to sabotage the logging machines.

Inheritance is not merely literal, but, literally, Yusuf bequeaths his children his money. What does it mean for them to inherit a fortune whose grubby origin is not safely sanitised by time? Should anyone accept such an inheritance? What if one is denied an inheritance one has been expecting? This is perhaps to be Roz’s fate, as her mother worries she’ll squander any money she’s left. What happens when one person’s inheritance robs another person, or group, of their birthright? Yusuf’s bequests and legacy come with these and many more questions.

Roz and Harun are both haunted by memories of Salam’s beating—although what, precisely, did they witness? An unjustified attack on an innocent man? Just punishment for interfering with logging activities, as Yusuf and his chief henchman claim? A murder? Meanwhile the forest is haunted—literally, or not—by Pontianaks, vampire ghosts of women who die in childbirth, and the whole novel is haunted by what Borneo and its people are currently losing: the forest; its produce; its history, mythology and traditions; its languages.

Musa is determined to do what he can to preserve at least the memory of some of Borneo’s languages apparently fated to disappear. Yusuf’s (former) friend Crazy Auntie is an academic. One day she announces she’s started writing a book of poetry, Corpse Flower, named after the Rafflesia, the biggest flower in the world, which grows in Borneo. The collection is to include a poem called The Song of the Wood. Crazy Auntie wants to have it translated into every language spoken in the Bornean state of Sabah, before the more obscure amongst them are lost.

Musa gives us some of his / Crazy Auntie’s translations of The Song of The Wood. Even though the languages featured will be unknown to almost all readers, simply seeing the incomprehensible words is compelling and moving. (The final translation is into English, so readers’ curiosity as to the song’s meaning is eventually assuaged.)

Musa refuses to be cowed into writing solely in conventional English, but peppers his text with Malay and Manglish—a mix of Malay and English, with elements, too, of Tamil and Chinese. Here’s a taxi driver talking to Harun:

Pandai cakap Bahasa Melayu ya? You can speak Malay, eh? Bah. Where are you from? Dari sini? Wah! Cun. Kau tinggal di America all those years? Ahhhh, patutlah! I thought you were from New York, or like, K-pop star or something like that. Ensemboi! How much you earn, ah? Must be big salary in America. Wow, pandai cakap Melayu ya? Mashallah! Okay, jom.

The reader who cannot understand Malay may occasionally be puzzled—but there’s always Google translate. Readers will perhaps differ, but Musa’s decision not to patronise the reader by explaining every Malay word adds a layer of interest to his novel, and of vitality to his language, that more than compensates for any slight loss of literal comprehension here and there.

Roz and Harun both address questions of what it means to be Malay. As expats, they think about what links them to, and separates them from, those who never left Borneo. Also, they are of mixed heritage. Their mother, originally called Yeung Yin Lam, then known as Susan Yeung, is a member of Borneo’s Chinese diaspora, but when she married Yusuf she converted to Islam —not without qualms—and took the name Jenab. Surprisingly, Roz and Harun seem to have relatively little interest in their mixed heritage: after a trip to Hong Kong, Harun tells Roz he’d been “hoping to get in touch with the other side of our heritage, the one we always forget about.” Why do they always forget about their Chinese side? Musa doesn’t explore how being both Chinese and Malay impacted on Roz and Harun’s sense of themselves.

Musa treats the Bornean rainforest not just as a setting, or as a focus of moral outrage, but as a character, a witness to its own destruction, and as a poet with its own distinct voice, here lamenting its trees being turned into tables.

I AM FOREST

skinned alive,

shrieked through the mill,

shat out as plank & board, muscled down factory line,

grunted into place, picked & pondered & cleaved, dovetailed & grooved,

chiselled & stained, lathed & lacquered … there I kneel, legs spread, a procession of

perfectly produced tables,

prostrate on all fours.

Musa’s outrage is one readers will surely share, but though Fierceland is an angry novel, it never feels like it’s preaching, or lecturing; its urgency feels like an irresistible invitation to think, and to act.

You must be logged in to post a comment.