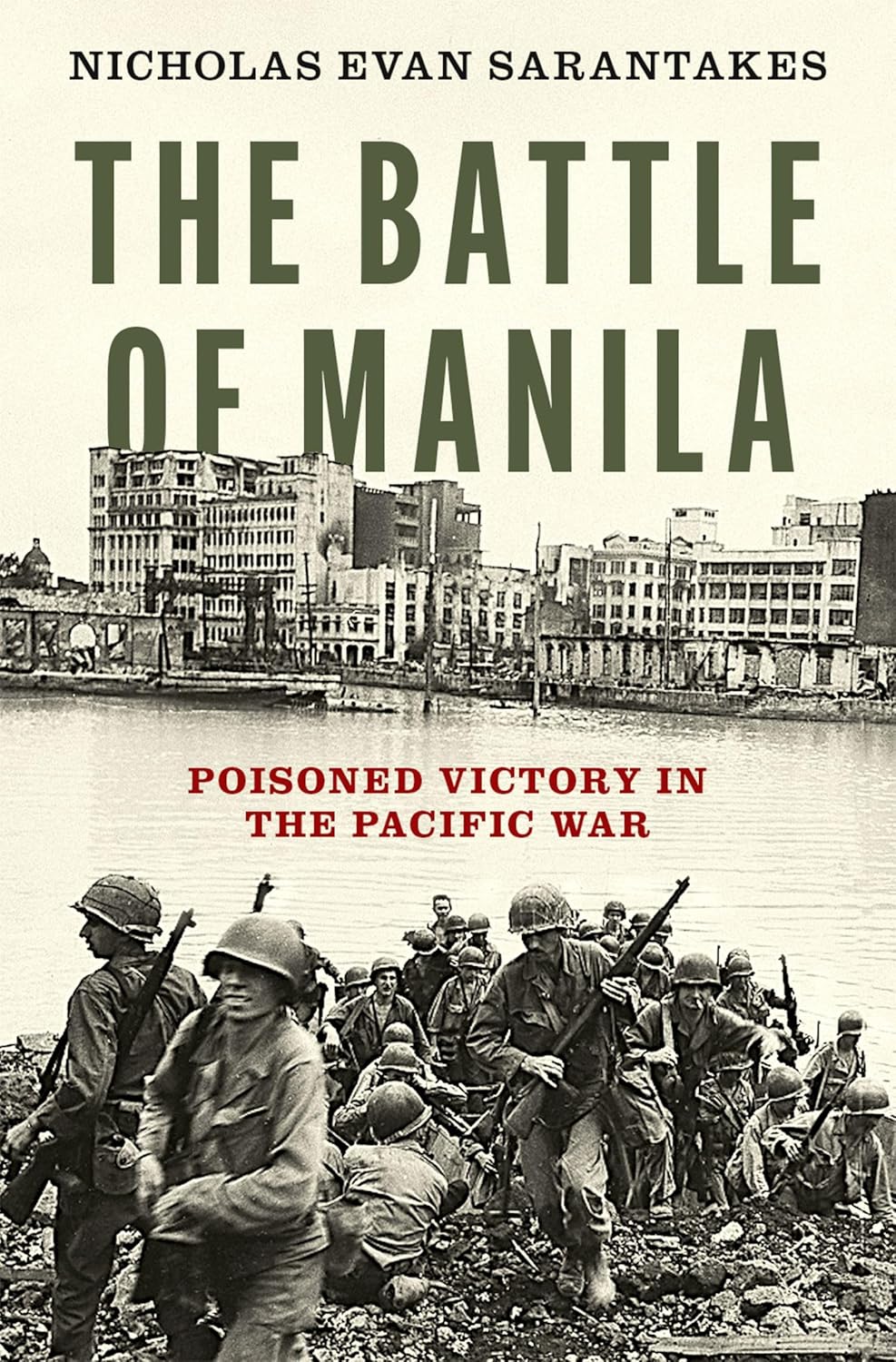

Wars are always replete with tragedies, and the World War II Battle of Manila, fought between 3 February and 3 March 1945, is one of history’s greatest tragedies. An entire city was destroyed, millions of people were made homeless, and more than 100,000 civilians were killed as Allied forces liberated the Philippine capital from Japanese rule. Naval War College Professor Nicholas Sarantakes, with meticulous research and vivid prose, has written the definitive history of this battle, which was an American victory but, in his words, a “poisoned victory”.

The American decision to invade the Philippines was a close call. The navy wanted to invade Formosa (Taiwan) instead. General Douglas MacArthur, who President Roosevelt ordered to leave the Philippines after it became clear that Japanese forces would defeat US and Filipino forces in March 1942, had famously promised to return to liberate the islands. At a meeting in Hawaii in July 1944, MacArthur persuaded the president to back his plan.

The Americans came ashore at Leyte, a southern Philippine island, on 20 October 1944. But MacArthur’s ultimate goal was the liberation of Luzon and the Philippine capital of Manila, which had been MacArthur’s home before Japan invaded. MacArthur, as Sarantakes notes, had an emotional attachment to the city that in some instances clouded his judgment in the coming battle. But Sarantakes believes the decision to invade the Philippines instead of Formosa was the correct one.

MacArthur had hoped to spare Manila from the ravages of war.

Sarantakes takes a holistic approach to describing the Battle of Manila. He describes the geographical influences on the battle, including landing sites at Lingayen Gulf, the topography of Luzon as the US Army drove south to Manila, and the urban environment that shaped the fighting. He delves into logistics and supply issues, the impact of Filipino guerilla forces, the tactics of both American and Japanese forces, intelligence successes and failures, friction between American commanders and divisions within Japan’s military leadership. And he views the battle from both the perspectives of commanders and individual soldiers.

The battle, Sarantakes writes, was a “fight determined by firepower and maneuver against static defense” and “a series of small, isolated tactical engagements”. He identifies and explains key events and “turning points” that shaped the battle: the landing at Lingayen Gulf; the march south to the city combined with an attack from the south; the joint nature of the military operations (air, land, and sea); MacArthur’s insistence on speed and maneuver; the urban environment that forced house-to-house, building-to-building fighting; the US breaking of the Genko Line (a fortified line of pillboxes near Nichols Field) that prevented Japanese defenders from escaping the city; the attack and seizure of Corregidor by airborne troops; and the fighting over strong points, including the police station, post office, Manila Hotel, Fort McKinley, government buildings and Intramuros (the older part of the city) that were occupied by Japanese defenders.

MacArthur had hoped to spare Manila from the ravages of war. But Japanese defenders made that impossible. Even during the early days of the battle, MacArthur imposed artillery and bombing restrictions on US forces in an effort to avoid physical harm to the city and its civilians. But at the urging of his subordinate field commanders, he reluctantly lifted those restrictions. That meant, as Sarantakes notes, that Manila would have to be destroyed to be freed from Imperial Japanese control.

The primary blame for Manila’s destruction and the enormous civilian loss of life, however, lies with the Japanese military forces who conducted a systematic campaign of rape and murder of civilians during the battle. Sarantakes recounts incident after incident of Japanese atrocities in what he calls “the methodical targeting of the civilian population” of Manila. Filipino civilians—men, women, children, the elderly and infirm—were raped, shot, bayoneted, slashed with swords and burned alive. When the battle was over, Manila, Sarantakes notes, was “a shambles” (more than 32,000 buildings had been destroyed) and had the stench of death. A priest described it as an “immense picture of desolation”. General Robert Eichelberger said, “It is all just a graveyard.” Japan supplied the poison for this “poisoned victory”.

It is hard to think of any World War II battle, or for that matter any battle of any war, that is not similarly “poisoned”.

Sarantakes’s account of the battle includes incredible deeds of valour that earned some American soldiers the Medal of Honor and other awards for bravery. He highlights the commendable leadership of relatively unknown US commanders, such as Gen Oscar Griswold who led XIV Corps in its march south to Manila, and Col George Jones who led the airborne assault on Corregidor. He also includes some fascinating anecdotes about US soldiers who fought in Manila who later became well-known personalities, such as Rod Serling of Twilight Zone fame, Sam Yorty who became Mayor of Los Angeles, and author Norman Mailer.

Sarantakes criticizes MacArthur for his failure to anticipate Japan’s defense of Manila, for the lack of strategic direction during the battle and for his cavalier pronouncements about “mopping-up operations” when hard fighting was still occurring. These are sound criticisms, but in the larger picture MacArthur had kept his promise to the Filipino people and American prisoners of war that they would be liberated from Japanese rule. And given the nature of the fighting, American casualties were relatively light.

The Battle of Manila was indeed a “poisoned victory”, but then it is hard to think of any World War II battle, or for that matter any battle of any war, that is not similarly “poisoned”.