Malay folklore is peopled—if that’s the right word—with a variety of supernatural beings, ghosts, and spirits, which reflect cultural anxieties, historical beliefs, and the blending of animistic traditions with Islamic, Indian and Chinese influences. Given this tradition has been a fundamental part of local storytelling for centuries, it’s unsurprising that horror is a staple of the Malaysian film and publishing industries. Malay-language horror movies often outperform Hollywood blockbusters in the domestic market, and locally published horror fiction is popular, in both English, and Malay.

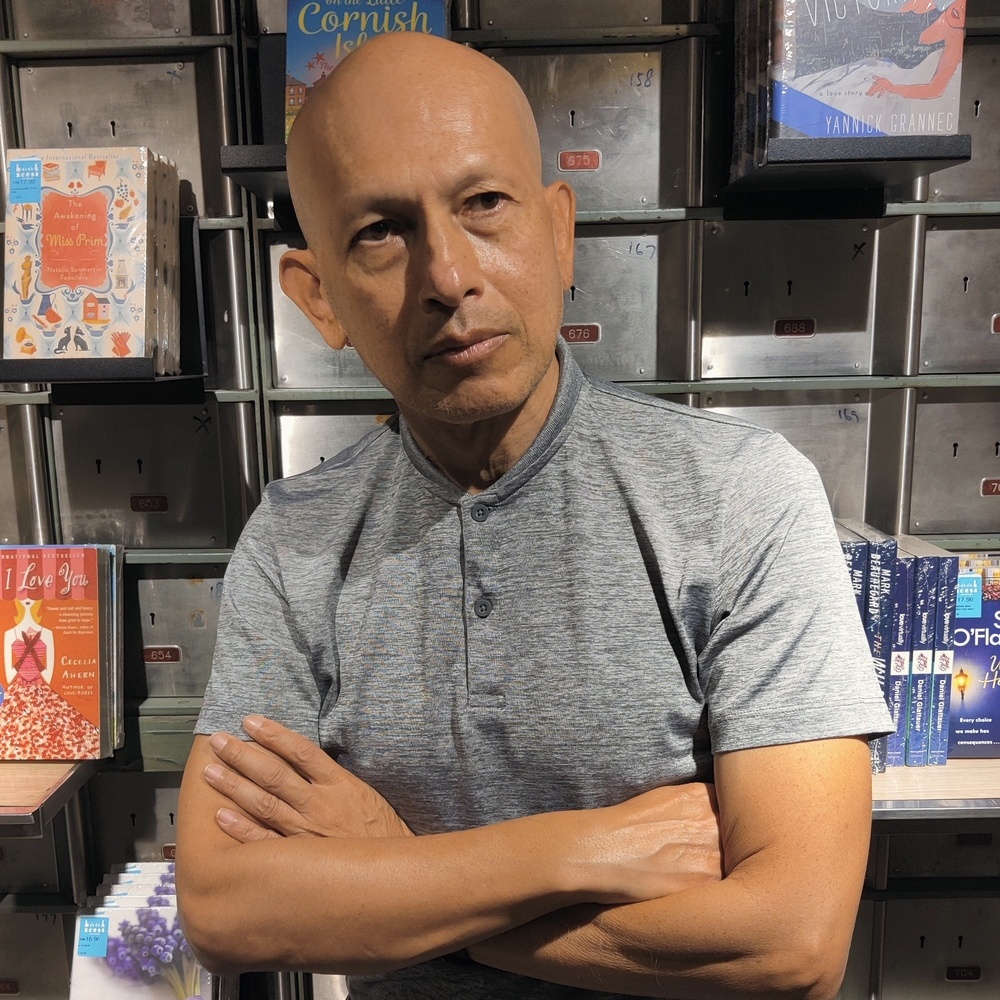

Tunku Halim’s contribution to the genre has been so significant he’s known as Asia’s Stephen King, and he’s a foremost proponent of world gothic—this takes familiar elements of gothic fiction and applies them in a global context, drawing from non-Western myths, legends, and folklore.

Horror is a staple of the Malaysian film and publishing industries.

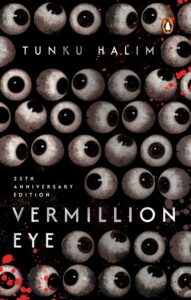

Halim’s Vermillion Eye, which was first published in 2000, is regarded as something of a classic of world gothic, and has now been updated in a 25th anniversary edition suitable for the age of the dark net, nomophobia, and social media influencers.

The plot demands the reader to ask how and why the murder of a man named Claymore (as in the Scottish sword, a weapon of brute power not of finesse) in Kuala Lumpur is 1957 is linked to the appearance in contemporary Sydney of a swarm of flies which can eat a man alive from the guts out, or else eat him so completely from the skin inwards that only dry bones remain.

The swarm is controlled by supernatural means, and it’s targeting four friends, two of whom, Gary and Baby Sykes, are quickly devoured. The remaining two are a small-time pimp called Rake Jamhorn (oh dear) and Jim Oxley, a great ox of a man, who’s so obese his stomach jiggles “like a sack of blubber above his knees”. Money worries have caused Jim to turn to the Ouija board, in the hope of receiving lottery-winning numbers. I don’t think it’s giving away too much to say he raises the spirit of Claymore, which then possesses him.

Once all the plot questions have been resolved, Rake and Claymore-as-Jim are involved in an exceptionally nightmarish showdown, a kind of wild mash-up of The Fly (the 1986 movie directed by David Cronenberg, which was itself a remake of the 1958 movie directed by Kurt Neumann), Metamorphosis (the 1915 novella by Franz Kafka) and possibly even Malaysian orang minyak (oily man) movies. (The oily man is a stock character in Malay horror movies. As his name suggests, he is covered in thick slippery black oil. He has made a pact with the devil to gain supernatural powers, consequently, he’s cursed to rape and murder women.)

Wherever he can, Halim uses simile to try to heighten a sense of foreboding. A cold floor feels “like the hardened skin of a corpse”, a fire throws “twisted shadows like mutilated people”, lace curtains hang “like used bandages” thunder sounds “like a plane crashing” and so on and so forth. This is all very well, but readers may feel Halim sometimes takes figurative language too far. Here, he’s foreshadowing Gary’s death, except now it’s not flies literally devouring him, but questions metaphorically doing the same:

Within himself, a thousand questions boiled. And he had no answers. He just felt them. The winged creatures droning in his head. Wings beating like rapiers in his stomach as they ate through his flesh.

Halim’s descriptions of Malaysia are lush and evocative.

Apart from the prologue which covers the events of 1957, most of the novel is set in Sydney, but when Rake Jamhorn realises his friends’ deaths have a supernatural component, and that he must be next on the fly swarm’s hit list, he decides to follow a fairly tenuous lead, and travel to Malaysia, in search of Alihuddin, a bomoh, a Malay shaman and healer, whom, he hopes, will be able to save him. He not only finds Alihuddin, who is ancient and decrepit, but also Hazni, a beautiful young medicine woman. In Sydney, Rake pimps a beautiful young prostitute, now calling herself Cindy Sweet, originally known as Lai Mui. Will Rake find true love with Hazni, or Cindy? Reader, that would be telling.

Some wobbles in Cindy’s backstory should have been caught in the copy-edit. Immediately after she’s introduced as “a Chinese girl from Vietnam” we’re told her grandparents fled Vietnam on a rickety, crowded boat, bringing with them their eleven-year-old daughter, who, in time, became her mother. This is her dominant backstory, with her grandmother’s and mother’s experiences on the awful boat referenced multiple times, but if Cindy’s a second-generation Australian, she’s scarcely a Chinese girl from Vietnam. On the other hand, we are also told she’d worked in her father’s liquor store in Vietnam, and when she’d first come to Australia the only job she could find was as a checkout girl.

Halim’s descriptions of Malaysia are lush and evocative, but never romanticising. Jake stays in Hotel California, a dive that “was far from the legendary lovely place that you could never leave. The air-conditioner looked decades old. It rattled noisily, spewing warm air and dust. From outside came the honking and revving of cars and scooters.” The Malaysians he meets wear Levi’s and baseball caps, and want to talk to him about motorbikes: they are thoroughly modern, whilst also believing in the supernatural and magic.

Given Halim’s place in world gothic, it’s surely both interesting and legitimate to ask whether any of the black magic he features in Vermillion Eye is specifically Malay. Ouija isn’t. Spirit possession isn’t. Insects as portents, omens or messengers from the spirits aren’t. The word bomoh is Malay, but belief in shamans was surely in the past universal. The hantu pusaka (inherited spirit) perhaps is—it’s a spirit passed from generation to generation within a bomoh’s family, and Alihuddin’s hantu pusaka is of central importance to Halim’s plot.

Halim’s Vermillion Eye will surely be enjoyed by all fans of supernatural body-horror, except for those with a phobia of flies, who should perhaps avoid it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.