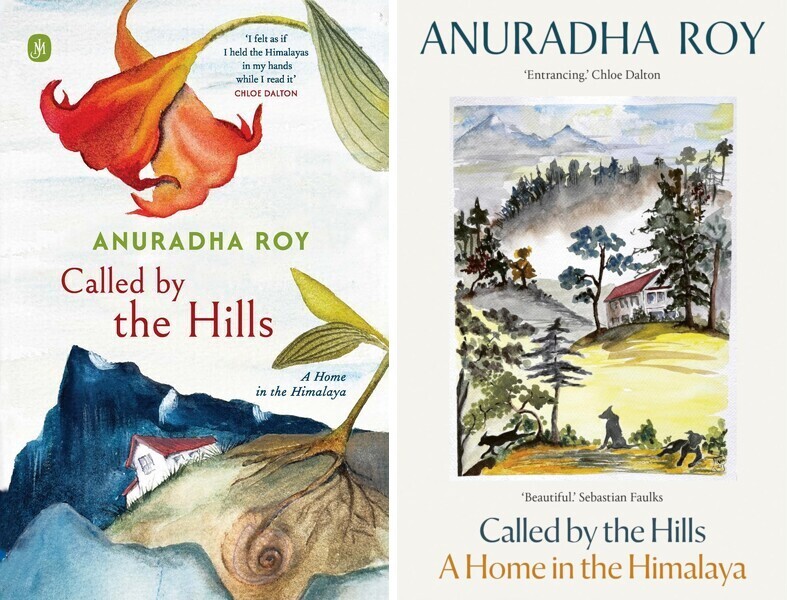

Best-known for her award-winning novels, Anuradha Roy’s first work of non-fiction Called by the Hills: A Home in the Himalaya, is a well-written book that goes beyond the boundaries of memoir and travelogue to examine the shifting life of a Himalayan valley through both anthropological and social lenses. The author and her partner retreat from the cacophony of city life, seeking solace and self-discovery in the mountains. Their decision to leave the freneticism of Delhi is also an act of resistance—an attempt to step away from an “externally moulded cultural change” and to understand how identity transforms in a vastly different landscape.

The book opens by examining how the mountains and valleys of Ranikhet shape local life, describing what Roy sees as a sense of inclusivity within the landscape. She portrays the valley and the community that lives there, noting how residents often describe themselves as being in harmony with their surroundings. Her narrative links ecological features with daily routines, including the role of sacred sites and long-standing traditions, which she suggests reflect both uncertainty and stability in people. “It is no accident,” she writes, “that most travellers of Ranikhet are looking for a way to reach God in His ‘earthly’ home.” The area’s wilderness, she observes, highlights the close relationship between residents and the land they rely on; a local song goes, “every grain is inscribed with the name of the person who will eat it.”

Roy portrays mountain communities as largely matriarchal and self-reliant, arguing that intergenerational and intergender knowledge—often lost in cities—still thrives here. At the centre of her account is Ama, the oldest woman in the village, whose thoughts on marriage, responsibility, nature, colonial history, and aging shape Roy’s understanding of the region: “alongside the medicinal caring, an unnerving streak of ruthlessness made her in my eyes a leading contender for the role of a matriarch.” Through Ama, Roy shows a community that is closely tied to its environment, socially self-reliant, and is built on the values of a functioning matriarchal tradition.

Roy goes on to explore the mountains through their flowers, finding quiet power and contentment in nurturing a garden. Turning a patch of hillside into fertile earth becomes a way to connect with the forests around her. She writes, “healing damaged land often starts with human effort”. While gardening, she uncovers polythene and glass in the soil—signs of ecological harm caused by negligence. The sterility of Himalayan soil, especially in Ranikhet, appears largely linked to plastic waste: “digging,” she writes, “we uncovered decades of refuse, and as we went deeper it turned into time travel.” The use of time travel here refers to the abundance of plastic waste. She despairs at the sterility of the soil due to plastic deposits and writes, “my soil, as far as I could tell, had little life in it.”

Once while walking on a beach Roy wonders, “if ‘roses trémières’ grow in the Himalayas?”. This introduces readers to the chapter named “illegal immigrants”, where Roy speaks about the invasive plant species—carried historically by ships, travellers, and colonizers. She also opens up about her illicit activity of bringing an exotic plant in Ranikhet wondering only about the rarity she will be able to hold with joy. But she soon realizes that “a pleasant ornamental plant can turn into a monster, driving everything else to the ground.” Roy doesn’t sugarcoat the contradiction. Rather, to justify her action she writes, “when science and emotion compete, feeling wins for me.”

Also featured are the strict religious rituals in Himalayan communities, which must be performed before any major task. When she visits a government official to seek permission to grow a garden of fruit trees, he tells her, “It is necessary in our profession to worship Mother Earth.” She is also instructed to observe Harela, a local Himalayan festival in which seeds are sown each year to invite divine blessings on the land. Roy notes that while the clerks and officials were enthusiastic about giving saplings to a gardener, they hesitated when the recipient was a woman. “They handed the saplings,” she writes, “because it would have been inauspicious for their future prosperity to turn me away.”

“What kind of room ought I have, to please such an important magazine?” she reflects on it at one point. “What would be writerly enough?”. She notices the privilege implicit in images of writers gazing over mountains or oceans, and wonders if her own surroundings—wet walls, leeches, crushed frogs—count as “writerly” at all. Her reaction is summed up in the phrase “sophar-sobad,” a colloquial twist on “so far, so bad”. .

Her desire to open a shop on Ranikhet’s main street grows from a wish to share something of herself with this small community. It becomes a metaphor for the creative process: a way to release what a completed work leaves behind. For Roy, the world itself resembles a shop—literary festivals are merely ornate storefronts selling writers and their artefacts. A shop of her own would not only be a workplace but also a space for exchange: a place where ideas and conversations can circulate freely.

Called by the Hills: A Home in the Himalaya is a compelling account of life in and with the mountains. Anuradha Roy writes in a voice distinct from her fiction—precise, personal, and fluid rather than layered and intricate. Her valley is full of small details and quiet patterns, revealing the mountains as they are and the communities that anchor them in compassion and kindness.