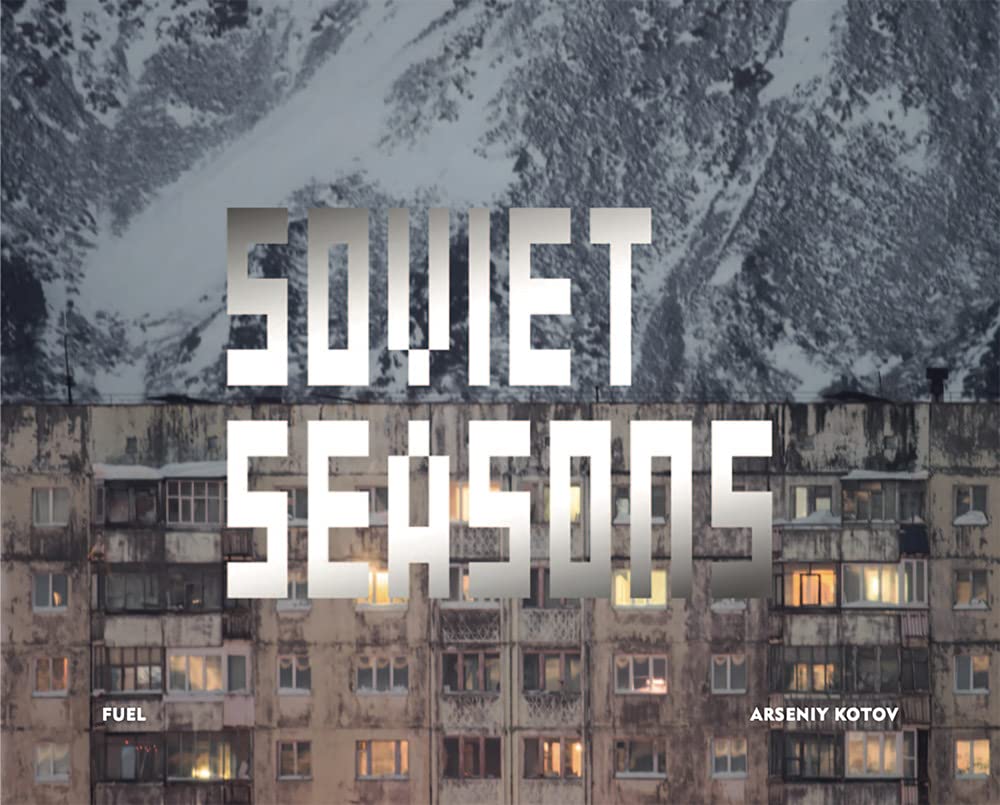

Photographer Arseniy Kotov has a thing for “modernist” Soviet architecture and has made a career of documenting it via (this being now a decidedly post-Soviet world) Instagram, entries to which were gathered into a book Soviet Cities which has been followed by Soviet Seasons, a collection of photos divided into four quarters, nominally by time of year, but more specifically, perhaps, by region: winter in Siberia, the Caucasus in summer, Central Russia in the Spring and Ukraine in the Autumn.

The book is almost entirely photos. Each section has a brief one-page introduction, taken (somewhat ironically, one supposes) from Soviet-era books. The photos themselves, briefly—but very informatively—captioned, largely speak for themselves.

The photos are beautiful—Kotov seems very good at his craft—even if their mostly architectural subjects are not: it’s not for nothing that the style is also referred to as “brutalist”; most of the buildings are considerably worse-for-wear and some are deserted and abandoned to the elements, victims of man-made disasters, economic in the case of Norilsk, nuclear in the case of Pripyat (Kotov has a subsection entirely on Chernobyl). And yet, Kotov finds humanity, art and message in the scenes he has captured.

The art is perhaps the most surprising, not so much the socialist realism sculptures, but rather the murals and in particular the mosaics, which can be both striking and a reminder of how public art, even propagandist public art, can work itself into the lives of inhabitants and survive for decades after the work’s ostensible political purpose has passed from the scene.

Kotov also captures the sometimes intentional, sometimes serendipitous, geometry of the various edifices, with discolorations and accretions adding a patina of sorts: not always that pleasant to live or work in, but a commentary on the how the best-laid plans of mice and men don’t always live up to expectations.

Kotov includes a few pre-Soviet structures as some as a small number entirely post-Soviet scenes: for balance, completeness, contrast or context, it’s not quite clear, but all—except for those completely abandoned—are still integrated with daily life, a daily life that has changed immeasurably since these buildings were erected, but whose echoes remain.

Those who visited (or lived in) the USSR or immediately post-Soviet Russia, Caucausus or Ukraine may well recognize and feel, against all odds, the tug of a certain nostalgia, one that Kotov himself evidently feels. The buildings are probably not much loved, but something will nevertheless be lost when they are all gone.

Peter Gordon is editor of the Asian Review of Books.

You must be logged in to post a comment.